How does reclusive President Bouteflika run Algeria?

- Published

President Bouteflika's last known public address to Algerians was in 2014

For many Algerians it is difficult to understand how their 82-year-old president, who suffered a stroke six years ago and can hardly walk or talk, can run the country.

This turned to disbelief when it was announced that Abdelaziz Bouteflika was running for a fifth term in April - he did not even turn up in person on Sunday to register his candidacy.

A wave of anger has moved students, teachers, lawyers and even journalists onto the streets in protest - they seem determined not to accept the continued status quo of rule by a virtually invisible leader.

Many worry that a failure to find a successor to President Bouteflika, who came to power in 1999, could lead to instability should he die in office.

The TV leader

His last known public address was in 2014, external - a victory speech to thank Algerians for their renewed confidence in his leadership after he won the last presidential election.

University students and their teachers have rallied in Algiers to demand President Bouteflika step down

He mentioned plans to "reinforce separation of powers, strengthen… the role of the opposition and guarantee rights and liberties".

Some viewed this as a sign of policy changes to come to ensure a smooth transition of power, yet there has been no evidence of this and his appearances since have been few and far between.

Algerians may have been lucky enough to catch brief glimpses of him on state television greeting visiting foreign dignitaries.

Or catch him at the opening of a new conference hall in 2016 - the footage shows him in a wheelchair, looking weak and tired, but alert.

But it was not until 2018 that it was clear that his party was pushing him forward as a contender for this year's elections.

He was at the opening of a restored mosque and two metro stations in the capital, Algiers. A few weeks later he was given a tour to see the construction of the Great Mosque of Algiers, a $2bn (£1.52bn) project billed as being the third biggest mosque in the world.

Divisions run deep

Yet again, however, the president, who won elections in 2014 despite doing no personal campaigning, does not have any strong challengers.

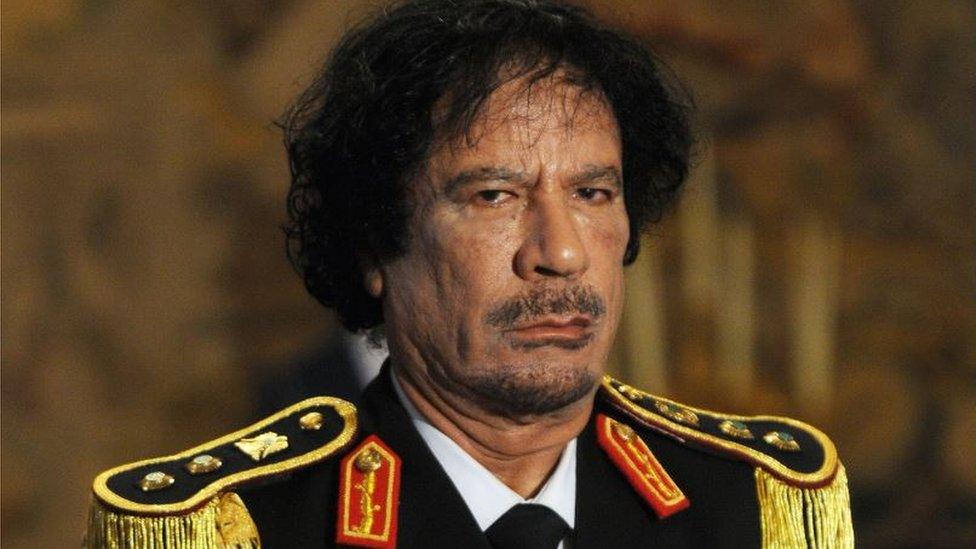

Muammar Gaddafi's rule in Libya shows the deep levels of distrust when a system allows one person to dominate

So why have the ruling coalition and the opposition not been able to put forward other viable candidates?

The opposition has historically been too divided - and as the president grew older and frailer the bickering within the ruling elite, including the army, has paralysed any political change.

The ruling National Liberation Front (FLN) has ruled the North African nation since gaining independence from France in 1962 after a bloody seven-year war.

"Le pouvoir" (the power), as many Algerians have come to describe those who run the country, has been centred around the party, some powerful generals and prominent businessmen.

You may also be interested in:

Mr Bouteflika's younger brother Said, 61, is the one holding sway in the presidency at the moment - controlling access to the president. The other important figure is Gen Ahmed Gaid Salah, the army chief of staff, who has centralised a great deal of power around him.

"The regime has always more or less worked by unaccountable factional decision-making behind the scenes - that continues to be the case but now it's just more obvious given that the figure-head is so obviously incapable of exercising governance by himself," Algeria expert James McDougal from Oxford University told the BBC.

The political class has included some of the opposition, who have either ruled in coalition or towed the government line over the years, which has largely discredited them.

It is a club that has been accused of corruption and nepotism.

In recent comments to the French media about the protests, prominent Algerian writer Kamel Daoud said the country's youth were being robbed of power by their elders.

He said by offering a candidate "who was almost dead", "le pouvoir" was showing its contempt for the young people in Algeria where more than 30% of people aged under 30 are unemployed.

Pervasive paranoia

But it is the legacy of Algeria's recent civil war which seems to have stagnated attempts at reform.

The brutal conflict ended in 2002 and weighs heavily on those who fought in it and have grown up in the wake of it - to the extent that some have seemed to be willing to trade some of their freedoms for stability.

Demonstrators defaced a sign taken to represent President Bouteflika, who uses a wheelchair

The violence left an estimated 150,000 Algerians dead, some of whom were "forcibly disappeared" by the security forces.

Even liberal opponents of the government are believed to have collaborated with the security agencies in the 1990s during the civil war against Islamist insurgents.

This has all led to a deep distrust at all levels of society - and has left little room for any genuine compromises or meaningful national dialogue to instigate change.

A Tunisian human rights defender, who spent many years visiting Algeria, told me she was always struck by this paranoia - to the extent that even local human rights groups were unwilling to share information with each other.

Other countries in North Africa have shown that decades of one-man rule leave deep roots. In Libya, neighbours, siblings and friends distrusted each other under Muammar Gaddafi's 42-year rule. He was deposed in 2011, the same year as Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, Tunisia's long-time ruler.

He had ruled Tunisia through "landslide victories" at the polls and a system that cornered the opposition, weakened it and ultimately reduced them to a side show.

On Sunday, President Bouteflika again offered dialogue - and constitutional reform in the event of his re-election as a way forward. This offer came in the form of a letter read out by a presenter on state television.

What is new this time is that he has promised that this will lead to early elections in which he will not contest.

While this could be an opportunity to ensure a peaceful transition of power, he will have to move quickly given his ailing health.

Yet Algeria's problems are, in the words of some regional observers, bigger than an ailing president.

It is a system that has kept running thanks to the many people who oil it.

- Published1 March 2019

- Published19 February 2015

- Published9 September 2024