Boeing 737 Max: What went wrong?

- Published

Pilots of the crashed Ethiopian Airlines Boeing 737 Max were unable to prevent the plane repeatedly nosediving despite following procedures, an initial report has found.

The captain and first officer followed safety procedures recommended by Boeing. But they couldn't stop the aircraft going into a fatal dive, external shortly after take off from Addis Ababa on 10 March, the report by Ethiopian investigators said. All 157 people on board were killed.

Aviation authorities grounded the entire global fleet of 737 Max aircraft in March after two fatal crashes in five months.

The Ethiopian Airlines crash followed a Lion Air crash in Indonesia in October, which left 189 dead.

What happened?

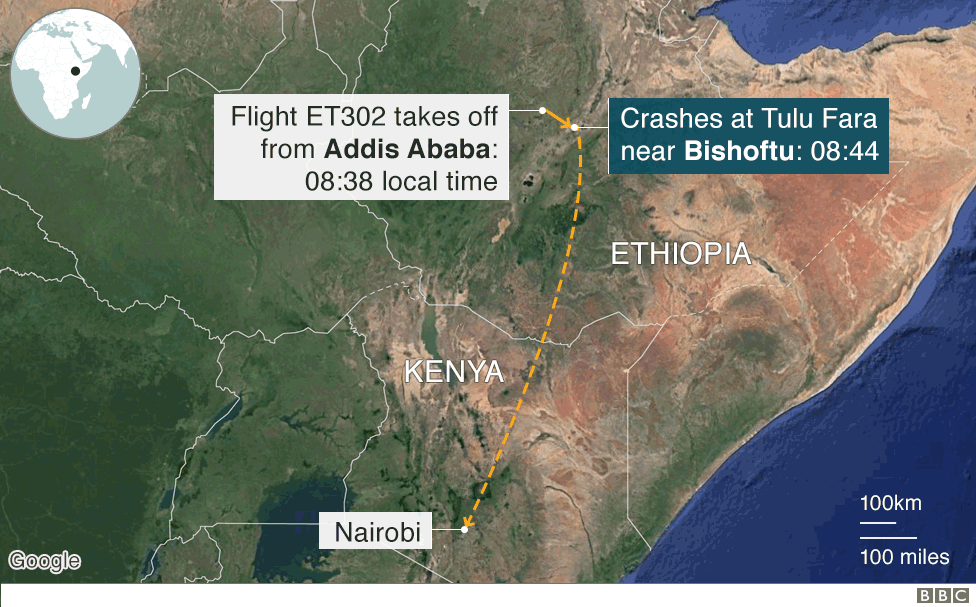

Flight ET302 took off from Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa at 08:38 local time (05:38 GMT) on 10 March for a two-hour flight to the Kenyan capital, Nairobi.

Six minutes later, at 08:44, it crashed 30 miles southeast of the airport, near the town of Bishoftu.

The impact was so great, both engines were buried at a depth of 10m (32ft), in a crater 28m wide and 40m long.

The preliminary report into the accident, by Ethiopia's Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau, said the plane's take-off appeared normal.

However, a short time later two sensors that measured the angle of the plane's flight began to record different readings.

This triggered an automated safety system which repeatedly pushed the nose of the plane down - something that was also recorded during the fatal Lion Air flight.

The Ethiopian authorities' report suggests the pilots followed steps to disengage the system, but even after manually trying to steady the plane, the system pushed the nose down until the aircraft crashed.

What is the computer system under question?

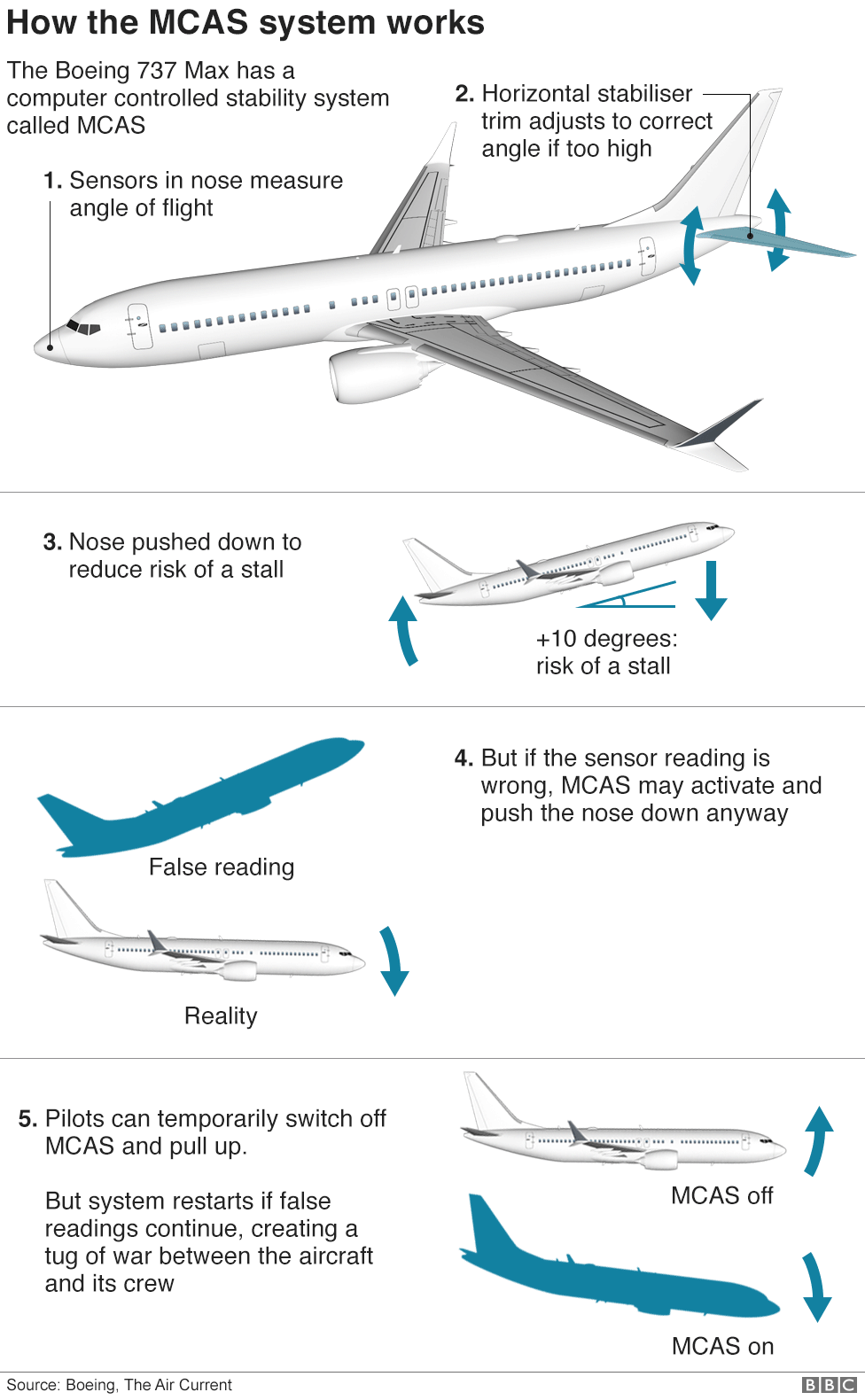

The report did not attribute blame for the crash, but a detailed timeline suggests the pilots were struggling to deal with an automated safety system - known as the Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS).

The system is designed to prevent the plane stalling when making steep turns under manual control.

A stall can happen when the plane flies at too steep an angle. This can reduce the lift generated by the wings, potentially making the plane drop.

To recover from a stall, a pilot would normally push the plane's nose down.

In the 737 Max, MCAS does this automatically, moving the aircraft back to a "normal" flight position.

The system then repeats the process if it detects the plane is still tilted at too great an angle.

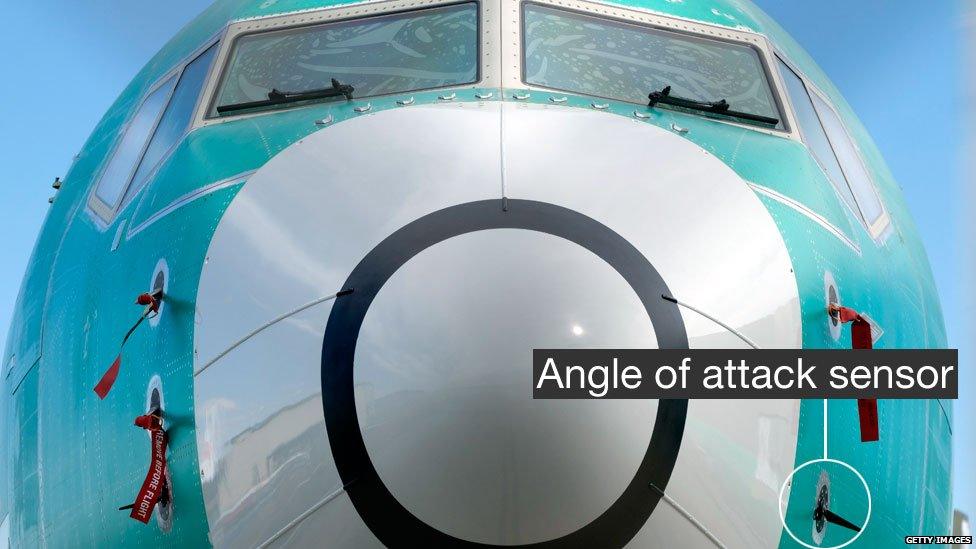

However, after the Lion Air crash, it was found the aircraft had experienced problems with a sensor which calculates the angle of flight, or "angle of attack".

Investigators believe faulty flight sensors may be possible factors in both recent 737 Max crashes

If this sensor gives a false reading, MCAS may activate and push the nose down when nothing is wrong.

Although the Ethiopian authorities' report does not mention MCAS by name, it does suggest the pilots were struggling to control the aircraft's angle of flight and says one of the sensors was giving erroneous readings.

The pilots' five-minute struggle

08:38 A sensor on the pilot's side falsely indicates that the plane is close to stalling, triggering MCAS and pushing down the nose of the plane

08:39-40 The pilots try to counter this by adjusting the angle of stabilisers on the tail of the plane using electrical switches on their control wheels to bring the nose back up

08:40 They then disable the electrical system that was powering the software that pushed the nose down

08:41 The crew then attempt to control the stabilisers manually with wheels - something difficult to do while travelling at high speed

08:43 When this doesn't work, the pilots turn the electricity back on and again try to move the stabilisers. However, the automated system engages again and the plane goes into a dive from which it never recovered

Source: Ethiopia's Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau

Dagmawit Moges, Ethiopia's transport minister, said that the flight crew repeatedly followed procedures recommended by the plane's manufacturer but "were not able to control the aircraft".

In a statement, the chief executive of Ethiopian Airlines, Tewolde GebreMariam, said he was "very proud" of the pilots' "high level of professional performance".

"It was very unfortunate they could not recover the airplane from the persistence of nosediving," the airline said in a statement.

Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg acknowledged that an "erroneous activation" of MCAS had occurred in both recent crashes.

But the company was "confident in the fundamental safety of the 737 MAX", he said, adding that impending software fixes would make the aircraft "among the safest airplanes ever to fly."

A final report by Ethiopian authorities, aided by air-safety experts from the US and Europe, is due to be published within a year.

What evidence could link the two disasters?

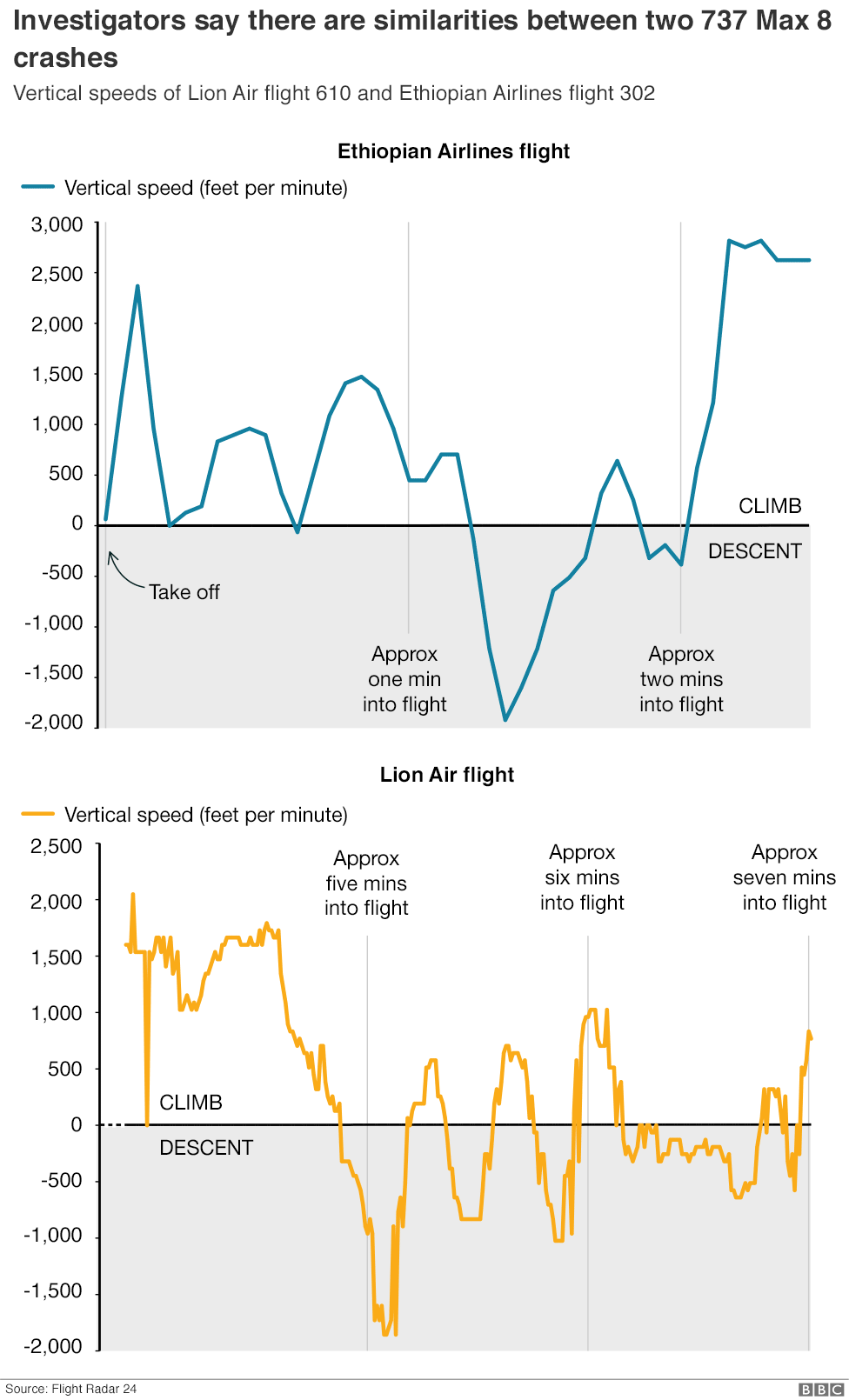

Investigators have pointed to similarities in flight data transmitted by the two 737 Max planes that crashed in Ethiopia and Indonesia.

Vertical speed readings, which show how fast a plane is going up and down, were erratic and suggest that both sets of pilots were struggling to maintain a steady ascent after take-off.

The US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which is investigating the crash alongside the Ethiopian National Transportation Safety Board, has said evidence collected at the site and satellite data showed the two flights behaved "very similarly".

"The evidence we found on the ground made it even more likely the flight path was very close to Lion Air's," said Dan Elwell, acting administrator at the FAA.

This ground evidence is reported to be a piece of wreckage from the tail section which indicates that the horizontal stabiliser was set to point the aircraft nose downwards.

The black box flight recorders - the flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder - from the aircraft are being examined by investigators in Paris.

After the Lion Air crash, Boeing issued guidance to pilots on how to manage MCAS, but a software fix to remedy the problem has been repeatedly delayed.

US regulators and safety experts are now asking how thoroughly the FAA and Boeing vetted the anti-stall system and how well pilots around the world were trained for it when their airlines bought new planes.

A warning light which could have alerted pilots to a problem with the flight sensors was not fitted to either of the planes that crashed.

Boeing simulator tests have also found that MCAS behaved much more powerfully than expected, repeatedly forcing the aircraft nose down.

In a simulation of the Lion Air flight, test pilots found they had less than 40 seconds to overcome the problem, external before the plane went into a unrecoverable nose-dive, the New York Times reported.

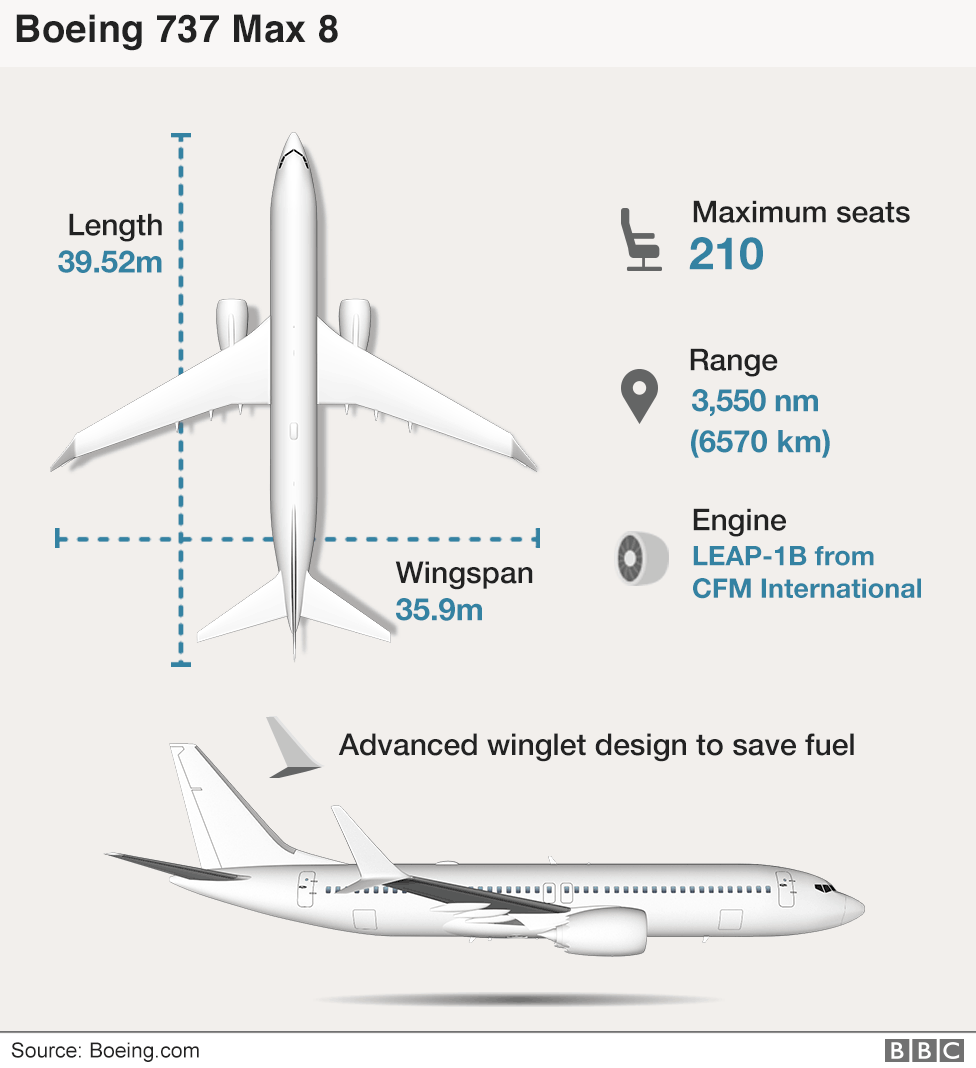

What is the Boeing 737 Max?

It is the latest in the company's successful 737 line. The group includes the Max 7, 8, 9 and 10 models.

The aircraft is the fastest-selling in Boeing's history. More than 4,500 have been ordered, external by 100 different operators globally.

By the end of January, Boeing had delivered 350 of the Max 8 models. They have been in commercial use since 2017.

The Max 8 that crashed in March was one of 30 ordered as part of Ethiopian Airlines' expansion. It underwent a "rigorous first check maintenance", external on 4 February, the airline said.

A small number of Boeing's Max 9s are also operating. The Max 7 and 10 models, not yet delivered, are due for roll-out in the next few years.

The Boeing 737 first flew in 1967 and was designed as a short-range narrow body airliner.

There have been more than a dozen subsequent models and it remains the best-selling commercial aircraft ever made, with some 10,000 produced.

An original 737 lined up next to a Boeing 707 and 747 in 1972

- Published4 April 2019

- Published10 March 2019

- Published13 March 2019

- Published11 March 2019