Cyclone Idai: What are the immediate dangers?

- Published

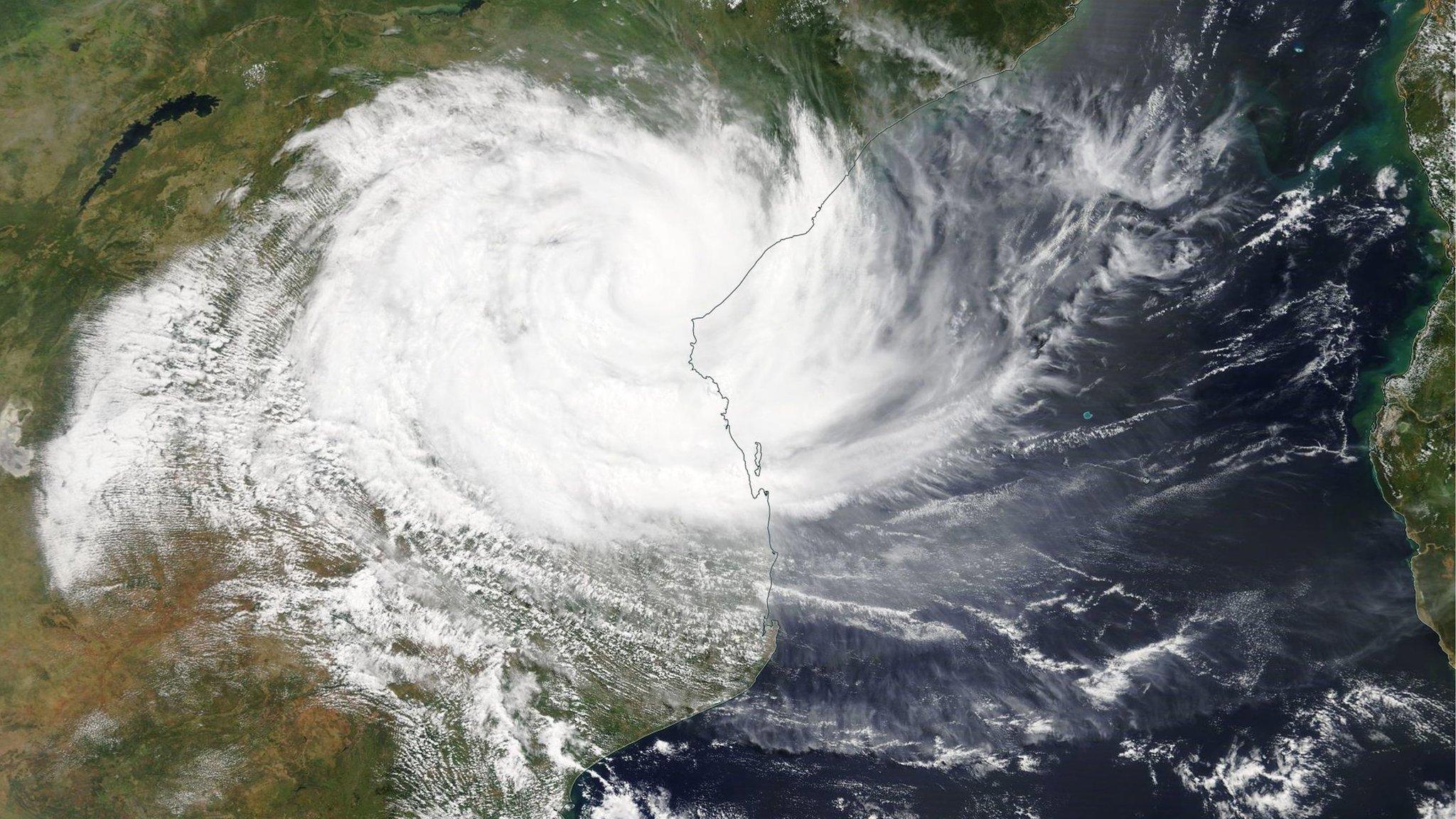

Parts of southern Africa have been left devastated after Cyclone Idai swept through Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe. Hundreds of people have been killed and hundreds of thousands more affected. Even though the cyclone hit Mozambique over a week ago, aid agencies are warning that the disaster is getting worse. Here are three reasons why:

1. More floods

The storm made landfall near the port city of Beira on Thursday 14 March, and the subsequent flood submerged much of the city.

But aid agencies warn that other areas continue to be at risk of becoming submerged.

That's because it is still raining.

Two rivers, including the Buzi, burst their banks after rain in Zimbabwe and Malawi at the weekend, sending even more torrents of water into Mozambique.

And more rivers risk bursting their banks, says Rotafina Donco, Oxfam programme manager in Mozambique.

She told BBC Newsday that this rain was affecting most of the rivers in Mozambique that flow into the Indian Ocean.

She said she expected more casualties.

As late as Tuesday, she received information that people in Manica province, near the Zimbabwean border, much further inland from the epicentre of the crisis, Beira, were stranded on rooftops because one of the rivers had burst and the area had become submerged.

In Mozambique waters are expected to rise by up to eight metres, putting at least 350,000 people at risk, says the Disaster Emergencies Committee (DEC).

A similar situation is playing out in Zimbabwe.

Herve Verhoosel, spokesperson for the UN World Food Programme said in a statement that heavy rains in Manicaland and Masvingo provinces continue to cause massive destruction.

The Marowanyati dam in Buhera, Manicaland has overflowed, raising river levels, he added.

2. Cholera

An outbreak of cholera could lead to the death toll increasing exponentially.

Cholera is spread through human waste in the water supply.

The flood water itself isn't the primary risk. Instead the risk comes because the existing drinking water supplies having been damaged by the flooding.

Beira residents are in desperate need of clean drinking water

This means people are finding it harder to find safe water. Larger groups of people are also sharing the same water supply, which increases the risk of cholera spreading quickly.

"It's bound to rear its head at some point," says Paolo Cernuschi, Zimbabwe Country Director at the International Rescue Committee.

But that doesn't mean inevitable disaster.

That's because cholera is relatively easy to contain when there is good healthcare available - people just need rehydration salts and to be put on an IV drip, he says.

So, Mr Cernuschi says, there is the "race against time" to get the healthcare all set up before an outbreak happens.

More on Cyclone Idai:

The worst-case scenario is that cholera breaks out in an area that is inaccessible, where there is no health care and spreads, Mr Cernuschi, said.

Currently an area his organisation is finding it difficult to access is Zimbabwe's south-eastern town of Chimanimani - making it difficult to tell whether cholera has already begun to spread.

Other waterborne diseases like typhoid and malaria also pose a risk, Mr Cernuschi says.

Malaria in particular is likely to spread because the aftermath of the flood there is an increase in stagnant water - the preferred breeding ground of mosquitoes that spread malaria.

Standing water also creates a risk of diarrheal diseases, Christian Lindmeier of the WHO told Newsday.

Even though there is water everywhere it is not safe enough to drink.

15,000in Mozambique awaiting rescue

3,000already rescued in Mozambique

440dead in Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Malawi

177km/hwind speed during Cyclone Idai

Access to safe water is vital to prevent any further disease, says Mr Lindmeier.

Relief efforts need to deliver clean water or water purification tablets.

And that's the issue.

"Getting there is the biggest challenge," he says.

The floods have cut off land routes and the only way to get to people is by air or water.

3. Starvation

While people may make it through the next few weeks with the energy biscuits and water purification tablets that are currently being airdropped, a more long-term threat of starvation still looms.

Mr Cernuschi explains that the cyclone has compounded a crisis that was already there.

He says drought in parts of Zimbabwe had already written off an estimated 75% of crops in the areas affected by the cyclone.

"Whatever crops that were being grown despite the drought have now been destroyed in the floods," he says.

He warns of a food insecurity crisis in the next six to 12 months - when people will face starvation as a result of the cyclone destroying their crops.

As for the country that is worst hit by the cyclone, Mozambique, a total of 600,000 people are believed to be in need of help, writes Andre Vornic from the World Food Programme.

Monica Blagescu, DEC Director of Humanitarian Programmes, warns that if more is not done, a "secondary emergency is approaching rapidly".

Fergal Keane: It's like an inland sea

- Published22 March 2019

- Published20 March 2019

- Published20 March 2019

- Published20 March 2019

- Published20 March 2019

- Published29 June 2021