Letter from Africa: Fighting 'uniform hairstyles' in Kenya

- Published

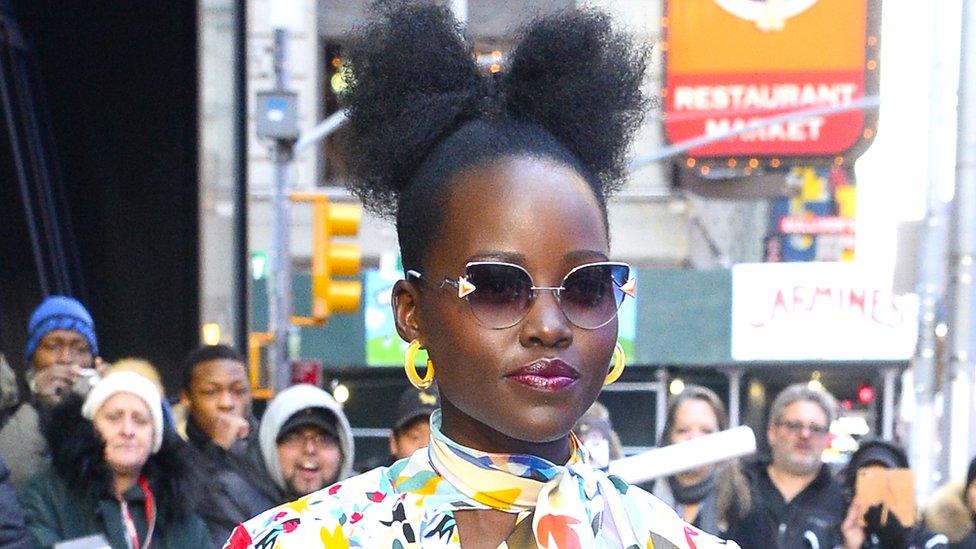

Some Kenyan TV presenters have been banned from having hairstyles like Kenyan actor Lupita Nyong'o

In our series of letters from African journalists, media and communication trainer Joseph Warungu looks at the state of Kenyan hair, amid a court case about discrimination on the basis of a hairstyle.

You could hear the screams of agony from the car park. My heart was racing as I walked into the hair salon that hot Saturday afternoon, not knowing what to expect.

Propped up on a giant barber's chair was a girl of about three.

One strong woman held her down to prevent her wriggling free, while another methodically worked a blow drier through her hair.

Unable to bear the screaming any longer, I asked: "Where's her mum?" One of the hairdressers pointed to a woman with her head buried under a hair drier.

She and the girl's father were quietly flicking through faded copies of lifestyle magazines, seemingly oblivious to the child crying herself hoarse.

As I waited for my own daughter's appointment with the hairdresser, I was deeply disturbed by the screams.

Olympic High School in Nairobi does not allow pupils to have dreadlocks

Almost three hours later, the little girl - whom I shall call "Baby Warrior" - walked out with red eyes, a distraught face and a new head of straightened hair.

She had lost the battle to keep her chunky, kinky hair.

This is the kind of experience that many, especially young girls and women, go through regularly in Kenya to conform to uniformity.

The Kiswahili proverb "akili ni nywele, kila mtu ana zake" meaning "hair is like brains, each person has their own" speaks to diversity - that everyone's hair is different.

But in Kenya we have been tearing our hair out trying to have a uniform hairstyle.

'Conditioned to mirror the white colonialists'

For one Kenyan teenager, the freedom to wear dreadlocks nearly cost her education.

Olympic High School in Nairobi sent new student Makeda Ndinda home in January for wearing dreadlocks, which are a symbol of her Rastafarian faith.

A Nairobi court has since ordered that she can attend classes with her hair covered in a black turban until her case is decided in May. The school wants her to shave off her locks.

Kenya's Supreme Court ruled that schools can decide on dress codes

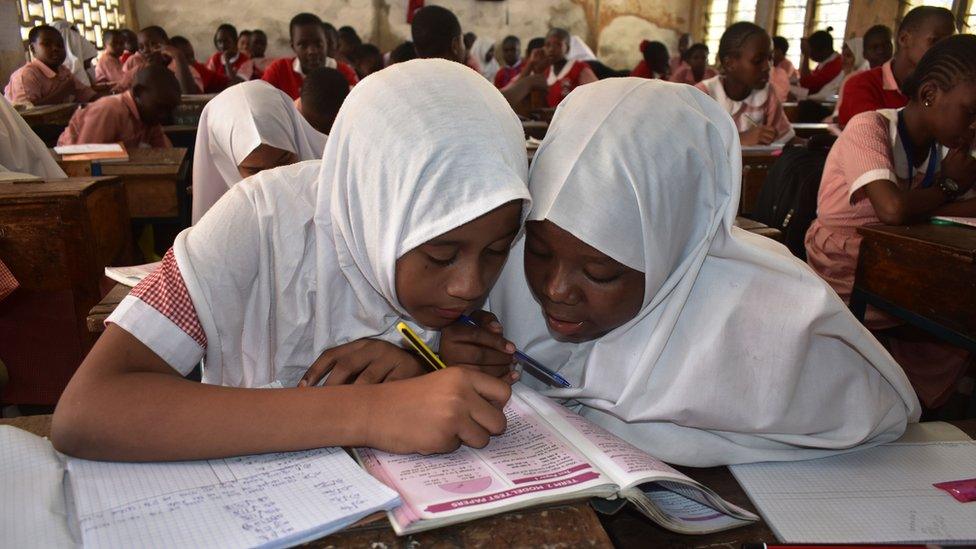

Days before, in a separate case about headscarves worn by Muslims, the Supreme Court - whose justices, ironically, cover their heads with artificial hair - overturned an earlier decision by the Court of Appeal that allowed Muslim students to wear a hijab in non-Muslim schools.

The court ruled that every school has the right to determine its own dress code.

So what's going on with our heads? A lot.

First of all I need to own up. I don't have any hair on my head - but I do have some hairy views about freedom of expression.

And hair is part of our identity and cultural expression.

"I think Kenya is increasingly becoming a moralist state," says Kevin Mwachiro, a writer and civil liberties activist. He blames this on "the growth of evangelism from the Christian right".

I've had these natural dreadlocks for many years, but people still ask me why I don't comb my hair"

Mwachiro believes the debate about hair is part of Kenya's struggle with its national identity.

"We tend to think we are an African nation, but we realise that we're very Westernised. We don't appreciate diversity. I've had these natural dreadlocks for many years, but people still ask me why I don't comb my hair."

The kinky v straight hair battles that "Baby Warrior" fought at the salon came from our colonial experience. The African was conditioned to mirror the white colonialists in speech, look and behaviour.

'Braiding was banned'

African women pioneers at university went through systematic training on how to dress and how to use knives and forks. They were even taught how to curtsy beautifully in case the British monarch came to visit.

Rose Lukalo, a media producer, had a direct encounter with that colonial experience that spilled over into independent Kenya.

"I was raised in Nairobi in post-colonial Kenya and most teachers were still white. We were not allowed to braid our hair. We were told we should tie it with blue or red ribbons and that we should brush our hair."

The hair industry in Kenya is estimated to generate $40m each year

But kinky African hair struggled to comply with these foreign concepts.

"Our hair can't do the things they wanted. They want it to lie flat, they want it to stay in position; they want you to tie it. But it doesn't respond to any of those things," she says.

And so in came the hot comb, perm and the hot iron to try to tame the African hair. This was all done at home with a charcoal stove because very few people could afford the salon.

More on the politics of hair:

As a little boy growing up in the village in the 1960s, I remember messing around with my mum's hot comb to disastrous affect - a burnt scalp, which had to be camouflaged with maize flour to avoid worse pain that would be inflicted on my backside should she discover what I had been up to.

Fifty-six years after independence we have failed to completely shake off the constructed identity we inherited as a nation, and continue to insist that the African hair conform to alien norms.

Not too long ago, the management of a national TV station sent a memo to female presenters saying they should not wear the Kenyan Hollywood star Lupita Nyong'o's look or natural hairstyles.

They had to have hair extensions on air.

And it's not just hairstyles that come under attack in Kenya's identity struggles. Global commercial interests also dictate what is beautiful and what is smart.

The suggestion was that if it's African, it's bad - and it should be restricted to weekends"

A few years ago, there was a TV advert for a laundry detergent, which asked viewers to "leave traditional African wear for the weekend".

This was in reference to a man in the advert who had washed his formal clothes using a competitor brand, which made them look bad and "African".

The suggestion therefore was that if it's African, it's bad - and it should be restricted to weekends.

But the tide is turning.

The heightened discussion on hair in Kenya is possibly a continuation and symbol of growing cultural consciousness and questioning among black people as evidenced in the recent rise of African music, film and entrepreneurship.

It's an example of the many spheres where oppression and the colonisation of the mind took place.

'Benefits of a bald head'

Now not only are women taking pride in their natural kinky hair, they are also - wait for it - shaving it all off.

Rhoda Odhiambo is a journalist whose bald head competes favourably with my own.

"Maintaining the hair was a lot of work. In the evening I had to plait it for bedtime, then undo it all in the morning. Two years ago I decided I'd had enough and chopped it all off," she says.

The reaction to Odhiambo's new look was shocking.

"In the early days people would ask me: 'Who has broken your heart?' Others would tell me: 'This is not you, what happened to you?'

Hair care can be time-consuming

So what have been the benefits of a bald head?

"Freedom. I get to sleep for much longer and I don't need a budget for hair, no weaves, nothing."

Steve Roots, who regards himself as the pioneer of dreadlocks in modern Kenya, identifies with Odhiambo's newfound freedom.

"Many people are going natural or wearing dreadlocks. You spend less time at the salon, there's no plaiting and no chemicals involved."

The founder of the Roots Dreadlock Centre, he now styles the hair of many celebrities in Nairobi.

And hair is a big industry in Kenya. It is estimated that it generates about $4bn Kenya shillings ($40m; £30m) each year.

Black-on-black discrimination

For Africans, hair is one of the main signifiers of our race and speaks directly to our identity and status. Indeed there is a social pecking order for hair - the silkier it is the higher your status.

I remember being called a derogatory word - equivalent to the N-word - on a trip to Somalia because of my "substandard" hair.

Only the fine, curly Cushitic hair on the heads of the majority of people in the Horn of Africa was seen as up to standard. Black-on-black discrimination is real.

For Mombasa-based psychologist Wanjeri Mahihu, hair is closely linked to one's emotional state.

"Your power is in your hair," she argues.

Muli Musyoka, a trichologist who runs a hair transplant clinic in Nairobi seeing up to 30 patients daily, agrees.

"When we started, people were not willing to share the fact that they'd done hair transplant," the hair consultant says.

"Our patients were all women. But now things have changed. Men comprise 40% of the patients.

"After the treatment, you'll see them smiling and upbeat. So I normally say that I restore people's confidence by restoring their hair."

Hair restoration doesn't come cheap. To camouflage a small scar can cost about $1,500.

That's how much we now value our hair.

We can only hope that the Rasta schoolgirl and Baby Warrior are allowed to grow up to value theirs too.

More Letters from Africa

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

- Published22 July 2015

- Published20 June 2018