The mystery of Star Wars and Tunisia's rundown Brutalist hotel

- Published

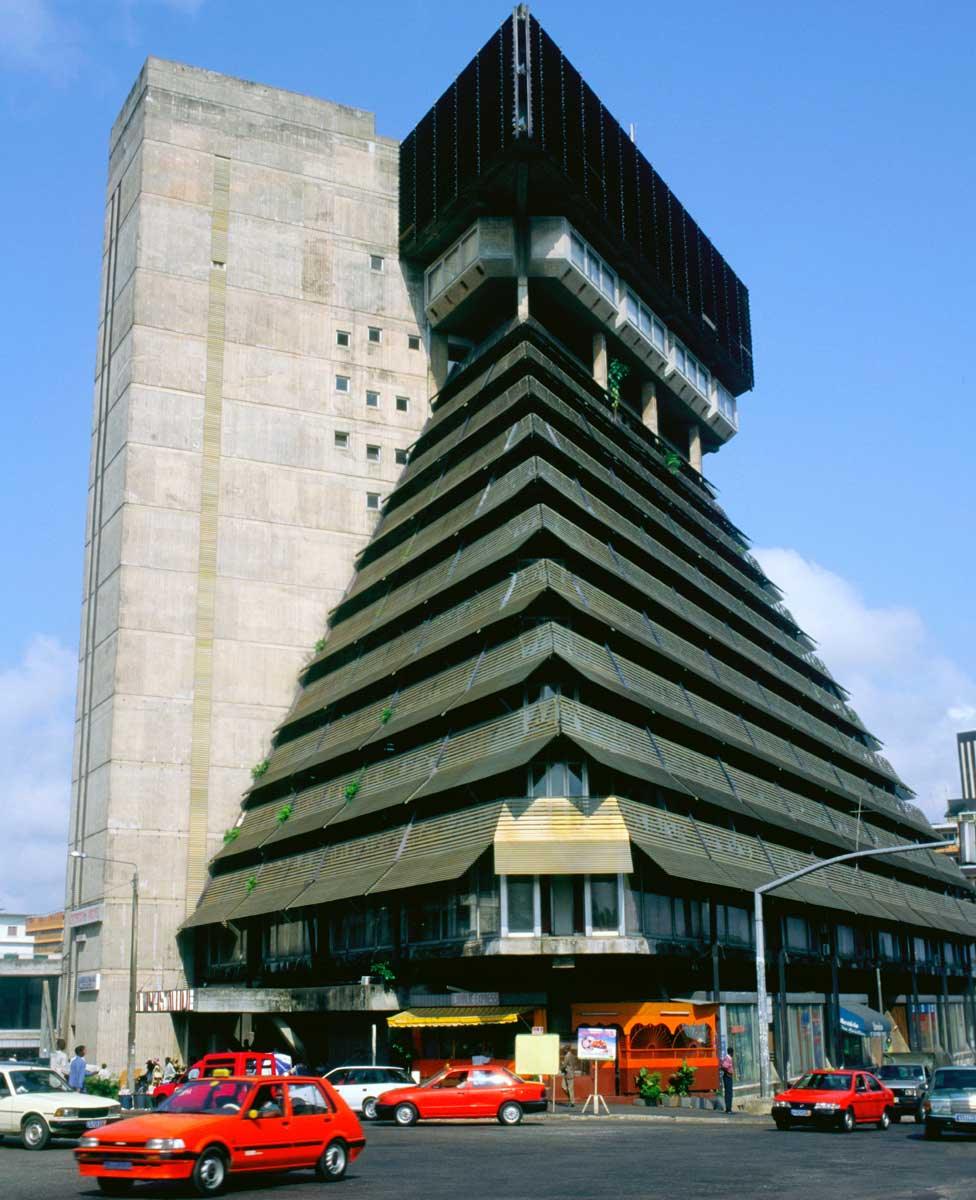

The Hotel du Lac has seen better days. Its distinctive shape, resembling an inverted pyramid or a bird in flight, has been making a statement on the Tunis skyline since the early 1970s.

It stood once for the ambition and poise of a young nation emerging from colonial rule, stretching its wings. Today it stands abandoned, prey to the elements after years of neglect, its fate hanging in the balance.

Demolition is a likely option. "The building is on life-support," says Sahbi Gorgy, a Tunisian architect involved in drawing up plans for the site on behalf of its Libyan owners.

He told the BBC that restoring the structure would probably cost more than replacing it, especially if further surveys confirm his suspicion that the steel frame has been weakened.

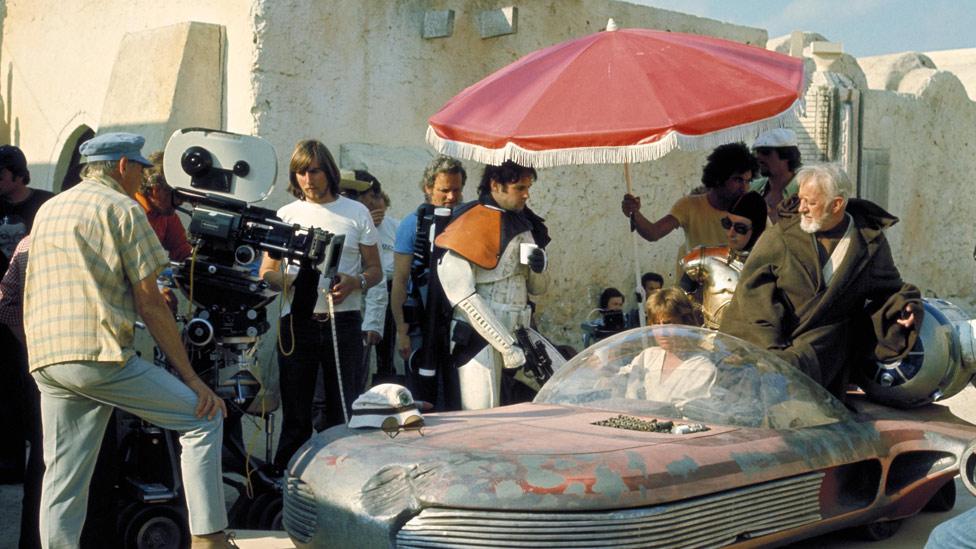

The Sandcrawler provided a fortified mobile home for the mythical Jawas of Tattooine

The threat to the hotel has prompted a Tunisian conservation group, Edifices et Memoires, external, to campaign for its preservation, highlighting its architectural pedigree. The building is a prime example of Brutalism, the 20th Century movement known for its bold, sculptural forms and its exposed, unadorned surfaces of concrete and metal.

"The hotel is a unique witness to a certain age," Mohamed Zitouni, a Tunis-based architect involved in the preservation campaign, told the BBC. "It's one of the rare buildings after Tunisian independence that shows vision and maturity."

Hopes for preserving the hotel are also being pinned on an apparent link to the original 1977 Star Wars movie. Its director George Lucas filmed part of his space fantasy in Tunisia, using the Sahara as stand-in for the desert planet of Tattooine. In Tunis, some believe he may have modelled the Sandcrawler, a huge tank-like vehicle featured in the movie, on the Hotel du Lac.

The desert locations that appeared in Star Wars have been preserved as tourist attractions. But can "the Force" also save a Brutalist hotel from demolition?

Did the hotel inspire the Sandcrawler?

"The hotel is supposed to have served as inspiration for the Sandcrawler in Star Wars," an online petition says, prompting reports about the link to the film, which some attributed to "legend", external.

The story of the making of the first Star Wars in the Tunisian desert has passed into folklore

Mr Zitouni subsequently told the BBC's Focus on Africa radio programme that Lucas had seen the building when he first visited Tunis, and was "inspired to draw, or design, a kind of sand tank… very similar to the shape of the Hotel du Lac".

A key crew member from the original Star Wars, contacted to see if there was indeed a link between the building and the tank-like vehicle, conceded that they did look "kind of similar".

But Roger Christian, the British director and set designer who won an Academy Award for his production design on Star Wars, believes any link would be "tenuous" at best.

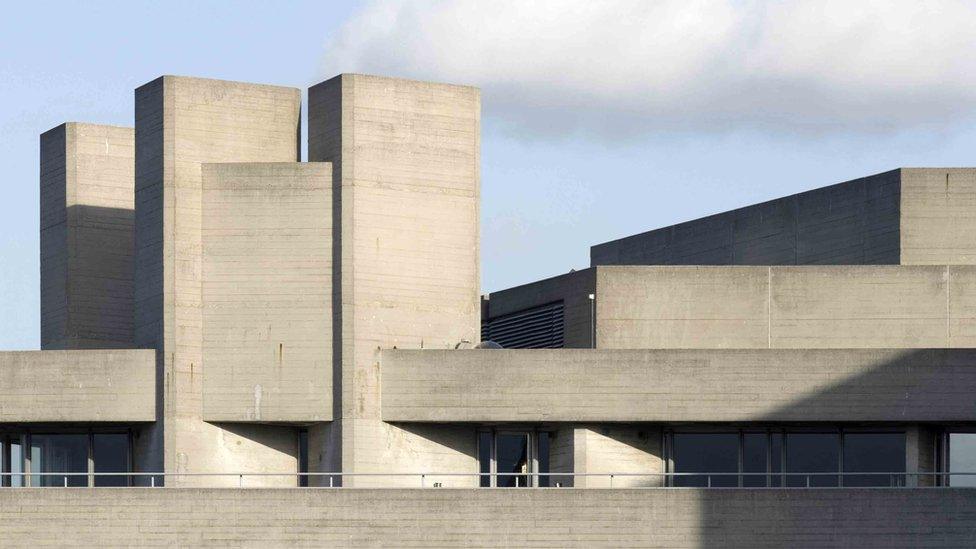

The Barbican Centre (architects: Chamberlin, Powell and Bon) in London is among the UK capital's best known Brutalist structures

Christian told the BBC the Sandcrawler owed its look to Ralph McQuarrie, the legendary US concept artist who shaped the aesthetic of all the films in the original Star Wars trilogy. Lucas enlisted McQuarrie early in the film-making process, while he was still writing the script, to illustrate his ideas. "Ralph did some beautiful drawings, and the Sandcrawler was drawn up pretty much as it is," Christian says.

The parts of the vehicle were constructed at Elstree Studios, near London, and shipped, piece by piece, to Tunisia. On set, Christian sprayed the model down with mud to make it look authentic.

Christian says McQuarrie produced the Sandcrawler design before Tunisia was being considered as a possible location. The decision to film there was made in 1976, after Lucas made a reconnaissance trip to the country on the recommendation of the set designer, John Barry.

Ralph McQuarrie's early sketches for the Sandcrawler, from the collection of Paul Bateman

Neither Barry nor McQuarrie are still alive. However, McQuarrie's friend and collaborator, Paul Bateman, confirmed to the BBC that the first detailed sketch of the Sandcrawler was ready by April 1975 - a year before Lucas visited Tunisia.

Nasa of the future

So where did McQuarrie get his ideas from?

In the 1950s, he had served in the US military in Korea, and the look and feel of army equipment - bulky vehicles, sleek weapons - can be seen in the machinery in Star Wars. During filming in the Tunisian desert, the model Sandcrawler was, in fact, mistaken for military hardware by a group of Algerian soldiers who were just across the border.

"They saw this name, Star Wars, and they thought we were building a war machine," Christian says. "They had to come over and verify that it was a film set."

Crawler Transporter vehicles shifted US space rockets and shuttles, such as the one pictured in the background

After the Korean war, McQuarrie made a living as a technical artist. He produced animation to accompany TV coverage of Nasa's Apollo missions, and he worked for Boeing, producing the manual for assembling the new 747 jumbo jet.

It was this apprenticeship, as a sort of master draughtsman of the US aerospace sector, that made McQuarrie's fighting machines of the future so compelling. His Star Wars artwork is like an advanced projection of US technological might - a space race that has outgrown its terrestrial rivalry.

Bateman says the idea for the Sandcrawler's massive tank-like treads came from the Nasa Crawler Transporter, a colossal tracked vehicle that lugged the Apollo programme's Saturn rockets to their launch site.

London's National Theatre (architect: Denys Lasdun) - like many Brutalist buildings - continues to divide opinion

By far the biggest influence on McQuarrie's art, however, was the pulp sci-fi of the 1930s through to the 1950s.

According to Bateman, the idea for the Sandcrawler's hull-like shape arose from sci-fi tropes of sand-ships and ships of the desert, and evolved into something that "quite literally resembled a ship".

Sci-fi architecture

Some of the ideas expressed in science fiction can also be found in Brutalist architecture. Brutalism emerged in the 1950s, in post-war Britain. As it spread around the world, it too would be influenced - like the sci-fi of that era - by the imagery of space exploration.

You may also be interested in:

"This was the prime time of the space age, so everything seemed possible," says Felix Torkar, an architectural historian who helps run the #SOSBrutalism campaign, external. "Daring, futuristic architectural designs were also very much of that time."

A typical Brutalist building, he says, might look visionary and simultaneously have a raw, monumental quality - "like the ancient ruins of a forgotten space-faring civilisation".

The heyday of Brutalism, from the 1950s to the 1970s, coincided with the process of decolonisation in Africa. Leading Brutalist architects were commissioned for many grand projects - museums, universities, hotels - in the newly liberated nations. Across the continent, dramatic concrete structures were erected to symbolise modernity and an international outlook.

"The ancient ruins of a space-faring civilisation" or the Brutalist Le Pyramide in downtown Abidjan? (architect: Rinaldo Olivieri)

Mr Torkar says Brutalist buildings tended to obey three basic rules - "expose the materials, expose the structure, and make it a unique, memorable design".

The Hotel du Lac is the work of an Italian architect, Raffaele Contigiani. Its prototype is thought to have been a similar inverted-pyramid design that he exhibited at the Zagreb International Fair in 1957.

In Tunis, the upside-down shape offered an elegant solution to problems with the site. As the ground was unstable, the foundations of the building had to be specially constructed - a laborious process. But the hotel's form minimised its footprint, which meant that the foundations would not have to be particularly wide, as long as they were sufficiently deep.

A Brutalist complex in the University of Zambia campus in Lusaka (architect: Julian Elliot)

According to Mr Torkar, the site of the hotel was also notorious for its stench, the result of its proximity to a lagoon that was, at the time, an outlet for Tunis's sewage system. The stench was worst at ground level. By providing more capacity at the top than at the bottom, Contigiani's design ensured that most of the hotel's rooms were lifted clear of the foul air.

Why is 'the Force' being invoked in Tunis?

Tunisia had been independent for 20 years when Star Wars, a myth of empire and rebellion, was filmed there. The country appealed to the film-makers for practical reasons. Lucas had a relatively meagre budget, and Tunisia was suitably cheap. Plus there were stunning desert locations with plenty of hotels nearby, mandatory for hosting a Hollywood film crew.

Tunisia's hotel sector was developed after independence to attract foreign visitors. Revenues from tourism have helped power the economy, accounting for some 8% of the GDP. But the number of foreign visitors plummeted after a series of terror attacks at tourist sites in 2015, and the sector is struggling to recover.

Building or spaceship? Set design for Ridley Scott's Alien, released in 1979

Brutalism had emerged from the wreckage of war and empire to provide a global house style for the public sector. It was chosen by governments worldwide to express a radical ideal - that the elected representatives of the people should use public funds to provide buildings for the use of the people.

In the last decades of the 20th Century, that ideal would fall out of favour, and its concrete forms would fall into ruin. Tellingly, the films of the time that are clearly influenced by Brutalism - Blade Runner, Alien, A Clockwork Orange - tend to portray bleak, dystopian futures.

Neglected, many Brutalist buildings would be held up to symbolise the failed policies of governments past. Sited on prime real estate, they would become ready candidates for demolition. Recently, however, there has been renewed interest in the movement, triggered by the fear that some of its finest structures could be lost forever.

Visitors to Tunisia visit the locations where scenes from the Star Wars series were filmed

The Sandcrawler, though not inspired by a building, would end up inspiring a building. In 2013, the film company founded by Lucas opened an office in Singapore, external that shared the vehicle's name and echoed its shape. Swathed in glass, it is in no way a Brutalist structure.

So what lies behind the claim that the Hotel du Lac was the model for the Sandcrawler? Mr Zitouni hints at a possible source, telling the BBC that people who worked at the hotel used to boast about how their building had inspired Lucas.

Every empire has its myths of origin, official and unofficial. For the Star Wars franchise, the Tunisian desert provides the backdrop for the official story. Meanwhile, the urban myth from Tunis testifies to its might.

In 2015, Fortune magazine estimated the worth of the franchise, external since its inception, including earnings from box office, home entertainment and merchandise. The total figure came to $42bn (£32bn) - just $1bn less than Tunisia's GDP in that year.

- Published28 November 2014

- Published11 December 2017

- Published9 October 2024