Libya migrants: UN says attack could be war crime

- Published

People gathered outside the detention centre after the air strike

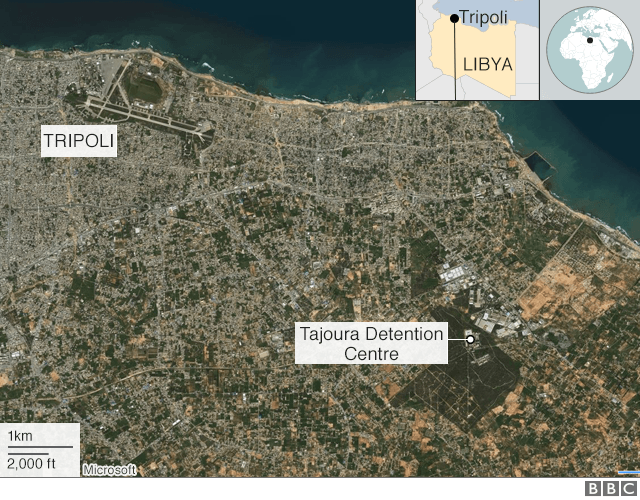

An attack which killed more than 44 migrants at a detention centre outside the Libyan capital could constitute a war crime, a UN official said.

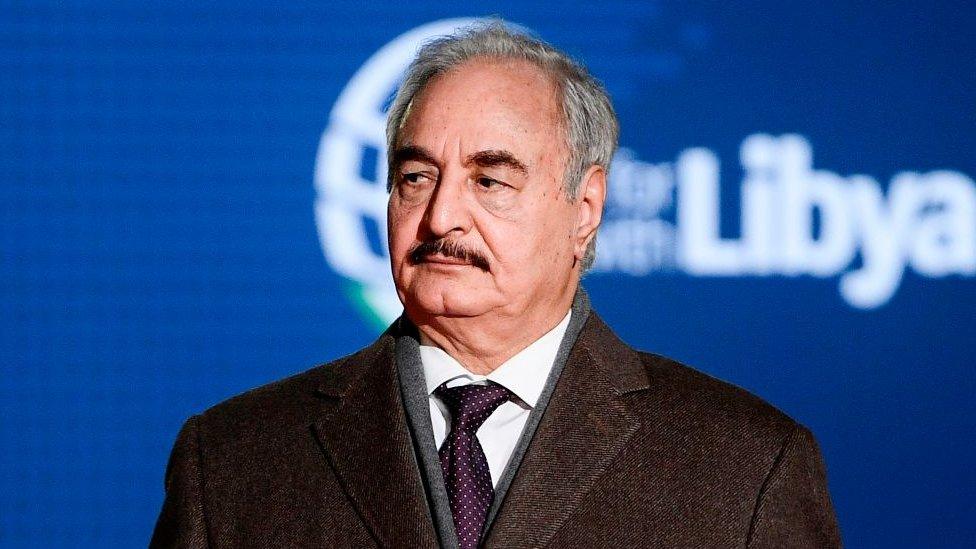

At least 130 people were injured in the attack, which the Libyan government blamed on an air strike by forces loyal to a warlord, General Khalifa Haftar.

Gen Haftar's forces accuse the government side of shelling the centre.

Most of the dead are believed to be sub-Saharan Africans who were attempting to reach Europe from Libya.

Thousands of migrants are being held in government-run detention centres in Libya. The location of the centre attacked on Tuesday and the information that it housed civilians had been passed to all parties in Libya's conflict, the UN's High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, said.

"This attack may, depending on the precise circumstances, amount to a war crime," she said. It was the second time the shelter was hit, she added.

UN Secretary General António Guterres said he was was "outraged" by the reports and called for an independent investigation "to ensure that the perpetrators are brought to justice".

Late on Wednesday, the UN Security Council held a meeting behind closed doors, but was unable to agree on a statement condemning the air strike, after the US said it needed approval from Washington before it could sign it, the AFP news agency reports.

It was unclear why this approval was not forthcoming, but the Security Council meeting ended without issuing a statement.

Libya has been torn by violence and division since long-time ruler Muammar Gaddafi was deposed and killed in 2011.

What do we know about the attack?

A hangar housing migrants at the Tajoura Detention Centre, which houses 600 migrants, reportedly took a direct hit.

Women and children were among the victims, Guma El-Gamaty, a member of the UN-backed political dialogue group, told BBC World Service.

An official in the Libyan health ministry, Doctor Khalid Bin Attia, described the carnage for the BBC after attending the scene:

"People were everywhere, the camp was destroyed, people are crying here, there is psychological trauma, the lights cut off.

"We couldn't see the area very clear but just when the ambulance came, it was horrible, blood is everywhere, somebody's guts in pieces."

The UN issued a stark warning in May that those living in the Tajoura centre should be moved, external immediately out of harm's way. "The risks are simply unacceptable at this point," the UN refugee agency said.

Analysis: An inevitable tragedy

By Sebastian Usher, Arab affairs editor

The UN and aid agencies have been warning that a tragedy like this has been all but inevitable as the renewed fighting in and around Tripoli has put migrants held in detention camps directly in the line of fire.

The plight of migrants was already desperate, prey to human traffickers and militias.

The UN has said that the airstrike on Tajoura shows that the EU policy of sending people trying to cross the Mediterranean to Europe back to Libya must be ended.

It's been successful in radically cutting the numbers of those getting into Europe by that route – although others have since opened up. But humanitarian agencies say the human cost is too high.

With General Khalifa Haftar's assault on Tripoli stalled, the chances are that his forces may resort to indiscriminate attacks that could endanger civilian lives further.

But the militias who hold the migrants in such appalling conditions, so close to what is now a frontline, must also take a share of the blame for what has happened.

Who is to blame?

The UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA), led by Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj, accused the self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA) of carrying out an air strike on the centre.

The "heinous crime" was "premeditated" and "precise", it said.

In Libya migrants are rounded up and held in government-run centres

The LNA - led by Gen Haftar - was fighting government forces in the area where the strike happened.

It had announced on Monday that it would start heavy air strikes on targets in Tripoli after "traditional means" of war had been exhausted.

The LNA said its warplanes had bombed a pro-government camp near the centre and pro-government forces had fired shells in response, hitting the migrant centre by accident.

A spokesman for the UN refugee agency, Charlie Yaxley, said it could not confirm who was behind the attack on the centre.

In a subsequent statement, the head of the UN Mission in Libya, Ghassan Salama, was quoted as saying: "This attack clearly could constitute a war crime, external, as it killed by surprise innocent people whose dire conditions forced them to be in that shelter."

Why is there war in Libya?

No authority has full control over Libya and the country is extremely unstable, torn between several political and military factions, the two most important of which are led by Prime Minister Sarraj and Gen Haftar.

Gen Haftar started an offensive against the government in April.

Libya crisis: The fight for Tripoli explained from the frontline

The general has been active in Libyan politics for more than four decades and was one of Gadaffi's close allies until a dispute in the late 1980s forced him to live in exile in the US.

After returning to Libya when the uprising began in 2011, he built up a power base in the east and has won some support from France, Egypt and the UAE.

Libyans have mixed feelings towards him due to his past association with Gadaffi and US connections, but do credit him for driving Islamist militants out of much of the city of Benghazi and its surroundings.

How vulnerable are migrants in Libya?

People-smuggling gangs have flourished in Libya's political chaos, charging desperate migrants from sub-Saharan Africa thousands of dollars per head.

Women and children are being held in camps close to fierce fighting in Libya

Human rights groups have highlighted the poor conditions at the detention centres where many migrants end up as the EU works with the Libyan coastguard to intercept migrant boats.

Italy, one of the main landing points for migrants from Libya, has taken a hard-line stance of closing its ports to humanitarian rescue boats, accusing them of aiding people smugglers. Instead, it wants to return any migrants found in open water to Libya - where most end up in detention centres.

Following Italy's objections, the wider EU proposed a compromise solution of setting up EU "assessment centres" in countries like Libya, where applications for asylum could be processed on foreign soil in a bid to break up the smuggling operations. Such a move was resisted by Libyan officials.

As things stand, migrants are not treated with consideration when it comes to housing them, said Leonard Doyle, spokesperson for the International Organization for Migration in Geneva.

"This detention centre is right beside a militia workshop that's been targeted in the past and it's been hit by shrapnel," he said.

"Migrants who are trying to get to Europe get picked up typically by the Libyan coastguard. They're brought back to land and then they're brought usually by bus to any of up to 60 detention centres around the city. It's really not a good situation."

- Published21 May 2019

- Published23 January 2020

- Published8 April 2019

- Published13 September 2023