Boris Johnson: Does Africa shrug, smile or scowl?

- Published

How should Africa react to Britain's new, Boris Johnson-led, Brexit-focused, government? With a shrug, a smile, or perhaps a scowl?

What does it matter to this vast continent if power changes hands, within the same party, in distant Britain?

The Shrug

The age of empire, of telegrams from the Colonial Office in Whitehall, is long gone, and so is the time when Africans cared about the politics of the island nation that once held the fortunes of half the globe in its hands.

These days UK sanitation experts, governance advisors and aid officials criss-cross the continent with little fanfare and, perhaps, diminishing relevance.

The same goes, to some extent, even for British royalty.

And that's as it should be. Africa is changing fast.

Today, the red carpet is rolled out with enthusiasm for visiting Chinese government delegations bearing cheques, solar power investors from the United Arab Emirates and India, US actors and music stars, Russian nuclear officials and Brazilian entrepreneurs.

China has become a major investor in Africa

Increasingly and crucially, the red carpet is also being rolled out for investors from fellow African nations - as a once disconnected continent, now linked together thanks to Chinese-built infrastructure, begins to focus less on outside help and more on what it can do for itself.

Yes, the good old Commonwealth is still a useful forum. And yes, the distant prospect of trade deals with a UK untethered from Europe is important too.

But Africa will, inevitably, be near the back of the queue for those deals, and besides, who knows if or when those changes will happen? Years of Brexit uncertainty, or, at best, a wobbly status quo, are likely.

"This is going to take years to unravel and will mean a long period of uncertainty for Africa," said the British peer, Lord Peter Hain, a vocal Remainer on the Brexit issue. "Even if there's a smooth Brexit it will mean a long transition… and a winding and complicated road ahead."

The complicated relationship between China and Africa

Meanwhile, British exports to Africa have slumped in recent years while other European countries, like Germany and Spain, have seen trade grow.

The UK enjoys close ties with many parts of Africa. That won't change.

But in the short term, this continent has other pressing priorities than worrying about the intricacies and agonies of Brexit. Not least, its attempt to renegotiate a two decades old economic partnership treaty with the European Union (EU) that manages to balance liberalisation with poverty reduction and the desire to protect Africa's weakest economies.

The Smile

Thank goodness. For decades, a bureaucratic and muddled EU has stifled, rather than encouraged, trade with Africa.

If Mr Johnson's government can break free of those shackles this continent - with its strong ties of language, history and culture, and its abiding appreciation of British values - will leap at the prospect of closer partnerships and new trade deals with London.

Boris Johnson visited Ghana when he was UK foreign secretary

"Brexit is positive for Africa. Boris Johnson and his government are particularly positive. If anything, restrictions went up [under the EU]," says Rob Hersov, a South African and the founder and chairman of Invest Africa.

If Britain's new government does leave the EU then, Mr Hersov predicts, "doors will open".

"The leftist colonial narrative is dead. The reality is that Africa has a very positive view of Britain. Everyone will be lining up to do deals," he adds.

Africa has a growing middle class

It is true that China has dominated investment on the continent for the past two decades, and that the UK, like the US, will have to play catch up.

But the infrastructure that Beijing has helped to put in place is opening up new markets and new opportunities for countries and companies ready to seize the initiative. A global-facing UK will be welcomed.

Of course, Africa is too big and complex to be viewed simply through the perspective of business.

Conflict has forced many Africans to flee their homes

Security, climate change, migration and health emergencies like Ebola remain crucial, and in each case, the UK has, and will continue to have, a significant role to play - roles that are unlikely to change dramatically under a Johnson government.

The UK is likely to continue contributing 0.7% of its national income on foreign aid and development - a commitment that its Department for International Development says enhances the UK's reputation as "a development superpower".

But Mr Johnson's government may well prefer to focus on supporting and financing African entrepreneurs, and less on the more traditional aid models so often criticised for being corrupt and inefficient. Depending on your perspective, that could be something to applaud.

The Scowl

Why should Africans brush aside, or overlook, the many derogatory comments the UK's new prime minister has made about their continent over the years?

Mr Johnson may hope his jibes about "watermelon smiles" and "Aids-ridden choristers" will be quietly dismissed as crude journalistic flourishes.

But a pattern is clearly discernible. Let's not forget that he has written - of the UK's relationship with Africa - that "the problem is not that we were once in charge, but that we are not in charge anymore."

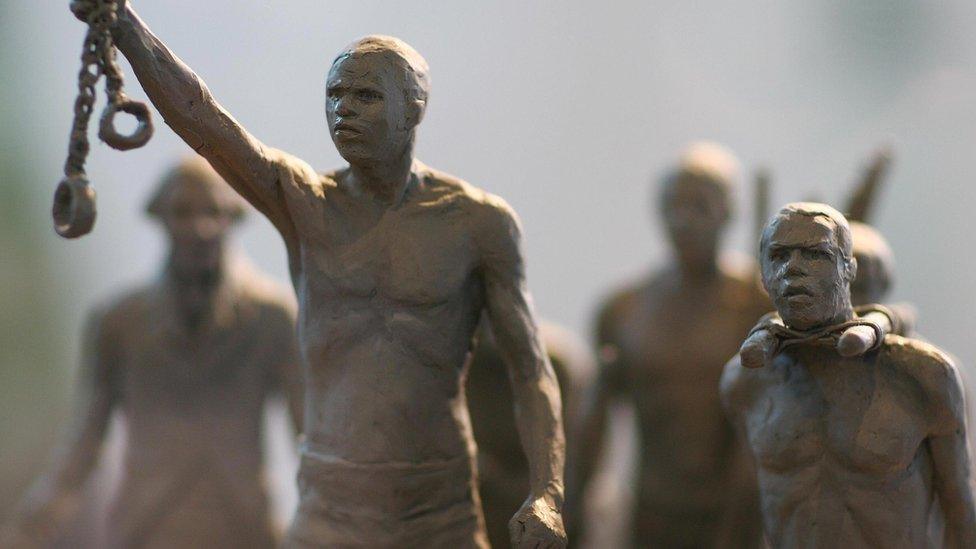

Many Africans were enslaved and colonised

It is true that relationships between nations and continents are complex and multifaceted. Just look at the UK's contortions in its dealings with the Trump White House.

Many African governments may seek to ignore Mr Johnson's past comments and focus on the future.

A few days of negative newspaper headlines and social media fury will inevitably come to an end.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But it is already clear, from Mr Johnson's time as UK foreign secretary, that his behaviour has not simply offended Africans, but has caused tangible damage. Take, for instance, the issue of decolonisation and, more specifically, the continent's support for Mauritius in its long feud with the UK over sovereignty of the Chagos Islands.

The UK's diplomatic isolation in Europe over Brexit, Mr Johnson's own clumsy handling of the Chagos dispute, and a growing sense of African unity and impatience, helped push the United Nations to ignore London's protests and to deliver the UK government a string of humiliating defeats at the UN and the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Expect more such friction in the years ahead. And expect some furious battles in the UK over its development agenda and what some, like Lord Hain, warn will be the "capricious siphoning" of aid money away to other projects.

More on Boris Johnson:

As one of the biggest nations in Europe, the UK helped to amplify the voice of Africa - and English-speaking Africa in particular - in the EU on all sorts of issues.

Post-Brexit UK will no longer be able to play that role, and unlike some of his predecessors, Mr Johnson has shown no obvious passion for African issues.

Finally, assuming Brexit does happen, and the UK is free to begin - or perhaps to complete in the case of countries like South Africa - negotiating those much-heralded new trade deals, it may quickly discover that, given it is no longer part of a formidable European market of 500 million consumers, a solitary Britain will find African nations are following Japan's recent example and driving a much harder bargain.

Come to think of it, that could be a reason for Africans to smile.

- Published25 July 2019

- Published25 July 2019

- Published23 July 2019

- Published24 July 2019

- Published24 July 2019

- Published14 July 2016