The story of Sierra Leone's Krio people - in pictures

- Published

The Krio people of Sierra Leone are partly descended from former enslaved Africans who fought for the British in the American War of Independence, in exchange for promises of freedom.

After the American victory in 1783, they fled with the British to the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, from where they were sent back to Africa, and the British colony of Sierra Leone. This had been founded for freed slaves, even before the slave trade was abolished in 1807.

Others who make up Sierra Leone's Krio population include descendants of black Londoners and Maroons - escaped slaves who fought against the British in Jamaica - and those who were freed from slave-carrying ships along the Atlantic route, who were all sent to Sierra Leone's capital, Freetown.

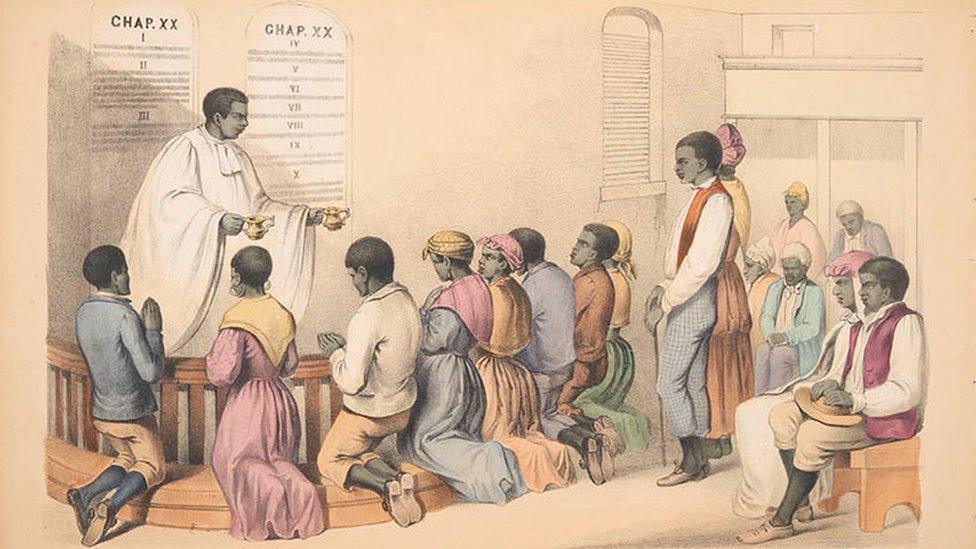

Some leading British abolitionists hoped that the freed slaves, having been exposed to British culture and Christianity, would go on to spread it across West Africa.

Today, Krios make up about 2% of Sierra Leone's population. They have their own distinctive identity, though British influence remains strong. The Krio language, spoken by most people in Sierra Leone, is based on English, along with various African languages.

"The Krios of Sierra Leone" exhibition is currently being hosted at the Museum of London Docklands, looking at the community's dress, architecture, language and lifestyle.

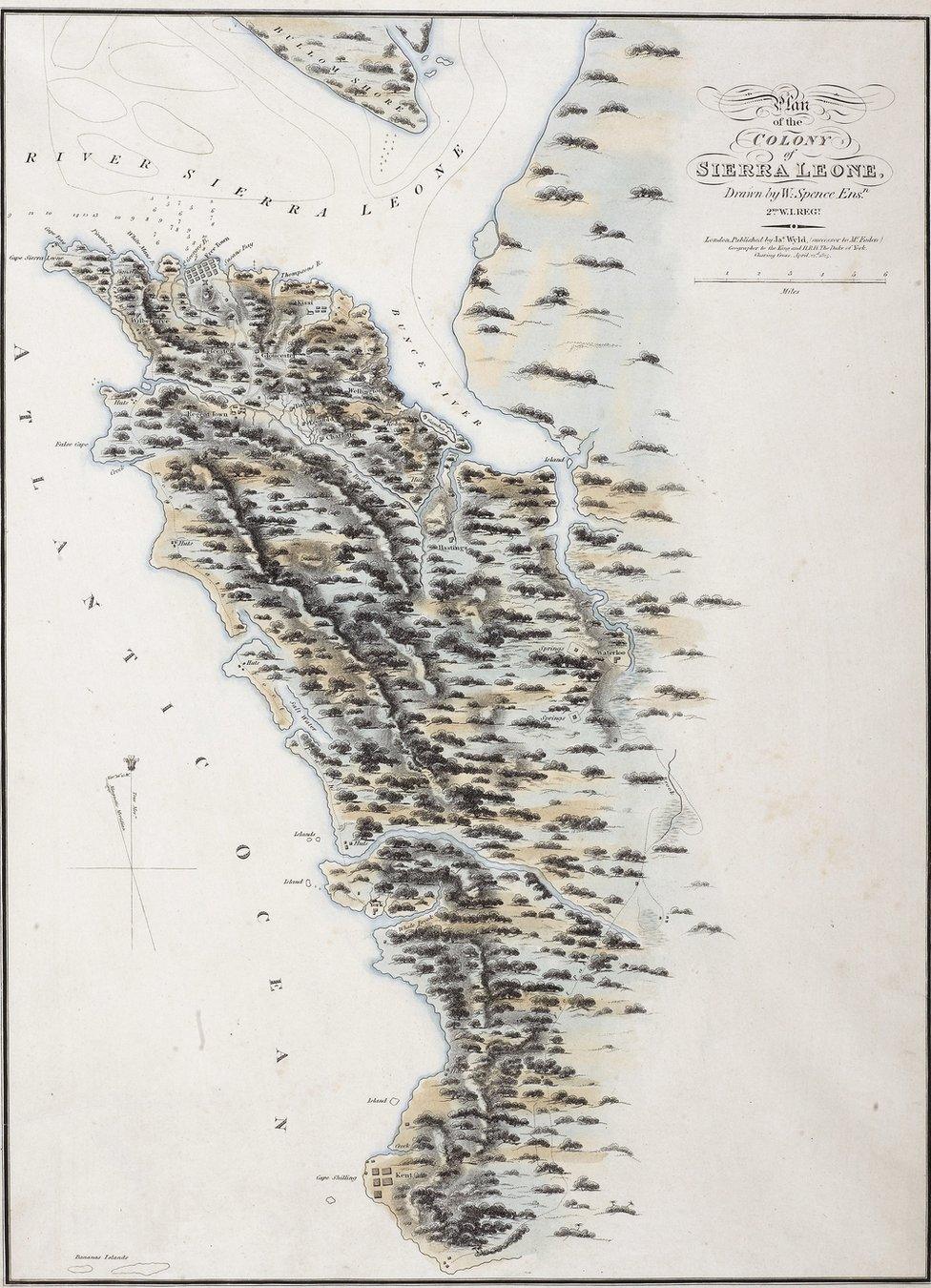

The above map was drawn by a British military officer in 1825 and details the villages founded by those who later became known as Krios.

Sierra Leone's British governors were keen for the new arrivals to adopt British Christian culture. They recruited missionaries to establish churches and schools.

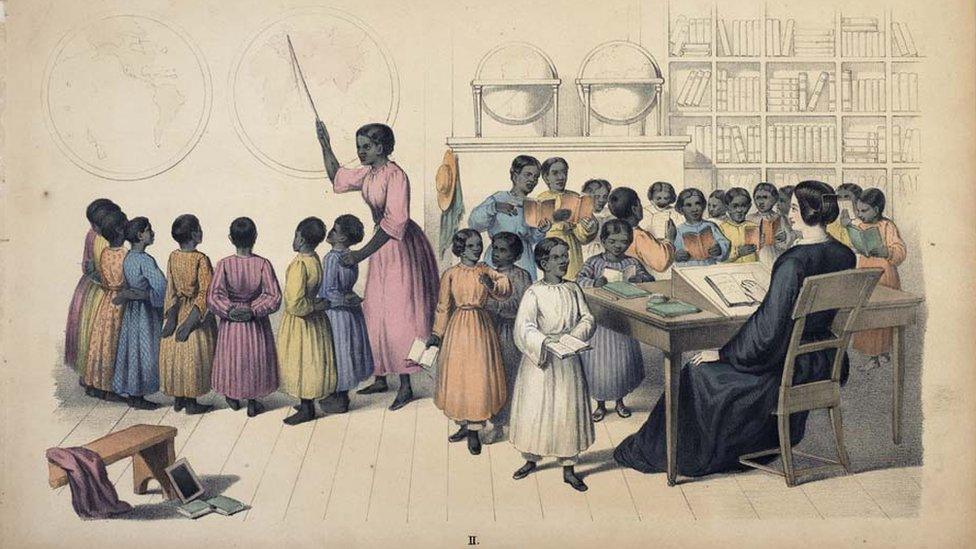

It was hoped that settlers trained there would become teachers, ministers, and missionaries across West Africa.

The image above shows a girls' school that still exists today. It remains one of the most prestigious in Sierra Leone.

This is a typical embroidered dress worn by Krio women. It has long sleeves, a belt and a lace petticoat underneath.

It is usually worn with a drawstring bag and a shawl.

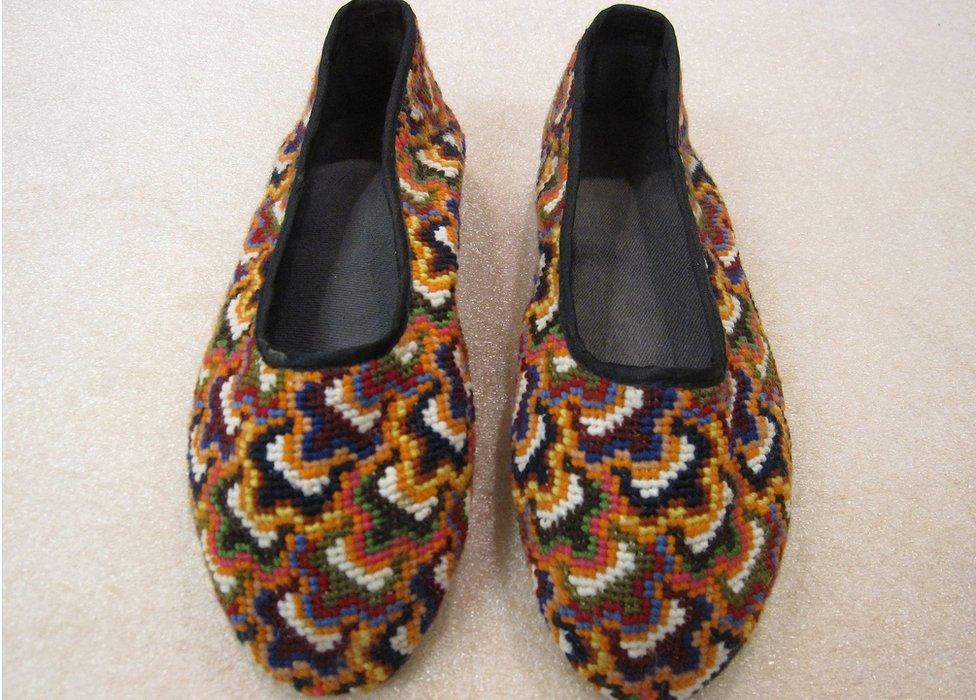

These "Victorian" pumps are also popular. The speciality art of embroidering the pattern is known as "marking carpet".

This particular pattern is called "cloud", while other patterns include "diamond" and "trellis".

This silver dish was presented to Thomas Cole, the acting colonial secretary of Sierra Leone, in 1831.

He was responsible for assisting those who arrived in the colony after being freed from captured slave ships.

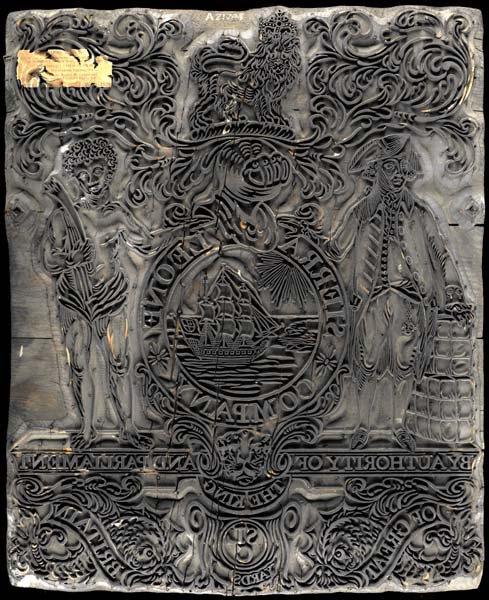

This wooden block was made around 1800 and bears the crest of the Sierra Leone Company.

The company founded a colony in Sierra Leone in 1792, but it later went bankrupt and the British government assumed control.

The country officially became a British colony in 1808.

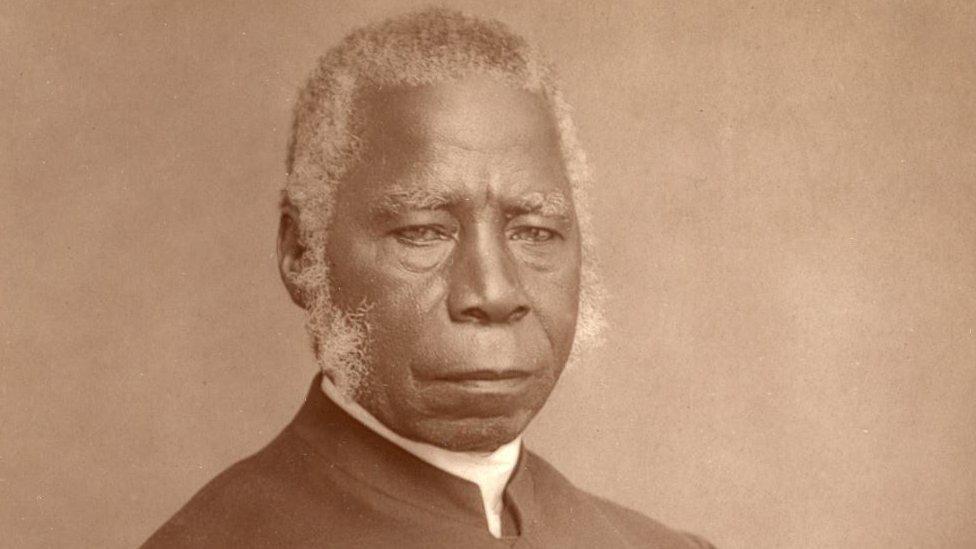

Samuel Adjai Crowther was born in Nigeria, where he was captured by slavers.

A British warship intercepted the slave ship he was being carried on and he arrived in Freetown as a "liberated African" aged around 13 years old.

Crowther was the first student of Fourah Bay College. He was ordained in England in 1843 and consecrated as Africa's first Anglican Bishop in 1864.

He is also known for translating the Holy Bible into Yoruba, one of the main languages in Nigeria.

British involvement in Sierra Leone began with the Royal African Company in the 1670s.

It was the first to settle and fortify Bunce Island in the Sierra Leone River for use as a trading post.

Prior to the 1807 act outlawing the slave trade, Bunce Island was known as a "slave factory" and hundreds of thousands of West Africans were held there before being transported across the Atlantic.

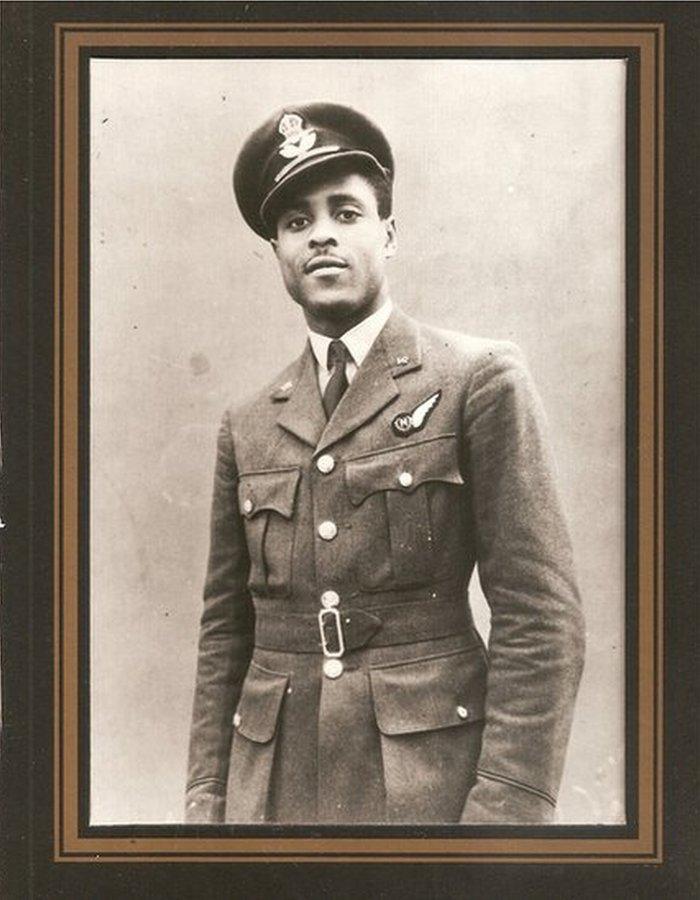

John Henry Smythe was born in Freetown and served in the Sierra Leone Defence Corps. Following the declaration of war in 1939, he volunteered for the British Royal Air Force (RAF), training as a navigator officer.

A year later he became navigator of a bomber squadron before being promoted to flying officer.

Smythe served on 27 bomber missions for the RAF in Germany and Italy.

In 1943 he was taken prisoner after being shot down by enemy fighters.

He spent 18 months in a German prisoner of war camp until the camp was liberated by the Russians in 1945.

At the end of the war, Smythe helped organise the return of West Indian RAF men from leave on the Empire Windrush and later became a barrister.

These houses on the American eastern seaboard, with their stone foundations and shingle roofs, were replicated in Sierra Leone by Nova Scotians - the enslaved people who retreated with defeated British forces to the Canadian province during the American Revolution.

The houses would become known as bod os (board houses), in the Krio language, which is widely spoken in Sierra Leone.

After 1940, construction of such houses was forbidden for fire safety reasons but this style was already in decline as concrete and stone became more fashionable.

All pictures subject to copyright.