Nobel Peace Prize: Has Abiy brought peace to East Africa?

- Published

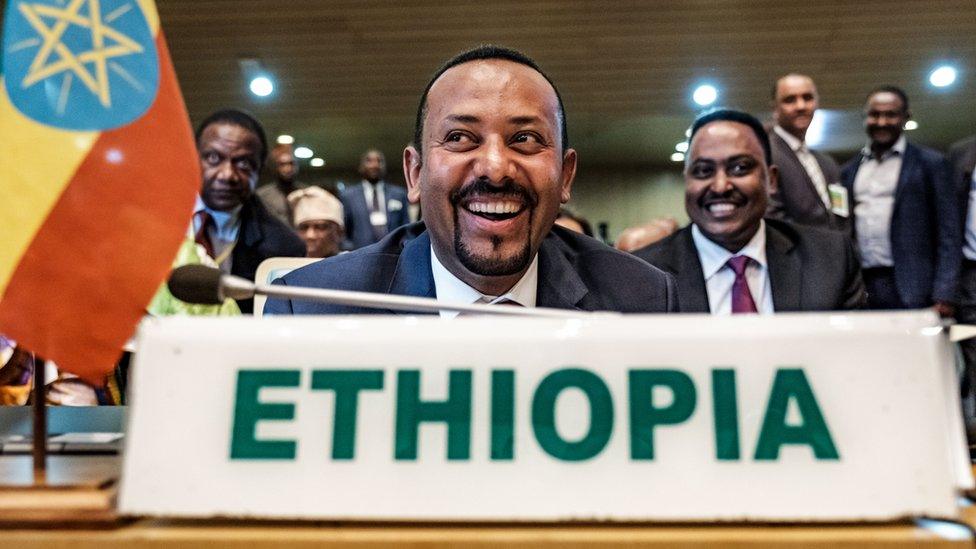

What has Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed achieved for him to be awarded this year's Nobel Peace Prize?

The Nobel committee said he had been chosen for his role in resolving the border conflict with Eritrea, and promoting peace and reconciliation both in his own country and in the wider East African region.

Mr Abiy's supporters hail his achievements as a triumph, but he does also have strident critics who point to the current situation in his own country, beset by ethnic tensions.

We look at his record.

A huge challenge

In 2018 Mr Abiy inherited a country with unresolved conflict across its northern border, in a region where instability had drastically held back economic development.

Within a few months, he had signed a peace deal with Eritrea.

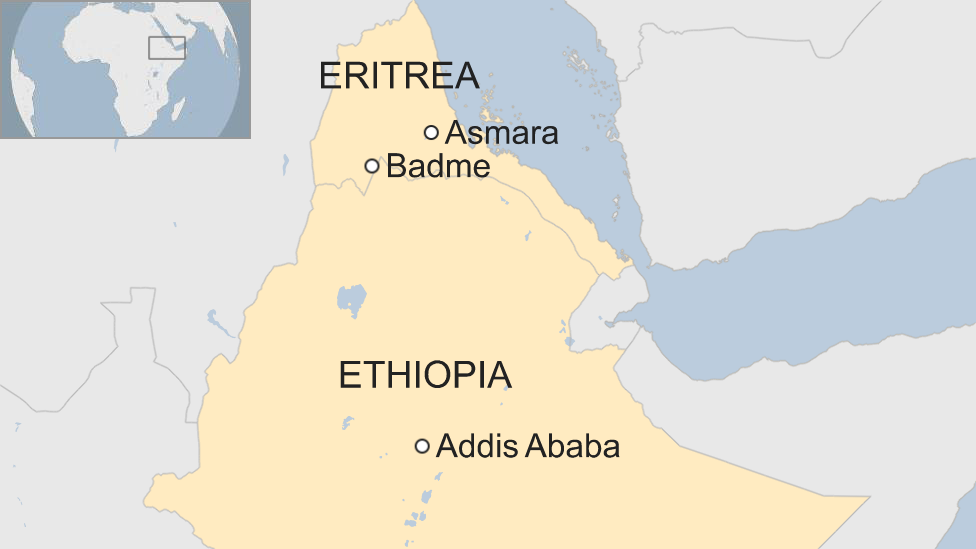

To achieve this Mr Abiy promised to hand over fiercely contested border territories, in particular the town of Badme, the focus of heavy fighting from 1998-2000, in which tens of thousands had lost their lives.

Mr Abiy has also been praised for bringing important democratic reforms to Ethiopia and for his conflict resolution efforts elsewhere in the region.

But let's start with the outcome of his peace deal with Eritrea.

Has the peace with Eritrea lasted?

At first, border towns opened up and goods and people were able to move relatively freely across the border which had previously remained closed and militarised.

However, following widespread euphoria in the country at reaching an agreement, there have been frustrations about the progress of the peace deal on the ground.

The town of Badme effectively remains under Ethiopian control, as the two governments tease out details of the agreement, and all the border posts which were initially opened are now shut. Some businesses in the border towns, which initially prospered, are now struggling.

Flights between the two capital cities, Addis Ababa and Asmara, have resumed.

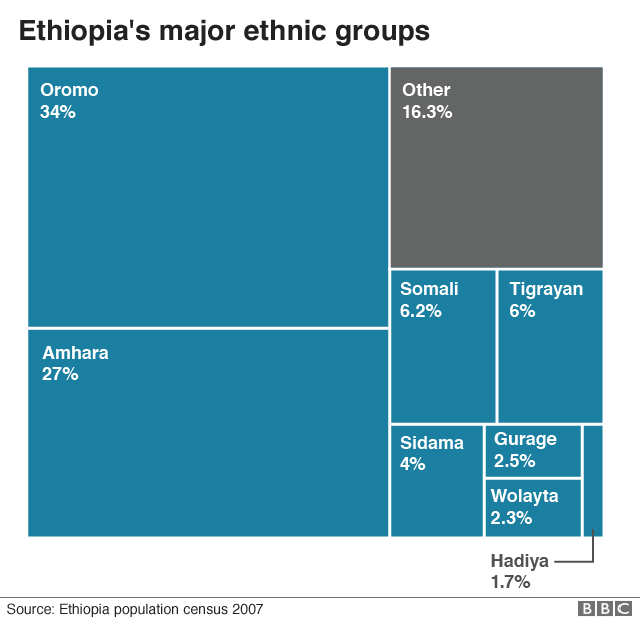

Some Tigrayans, the ethnic group in the north-east region that borders Eritrea, had protested at the opening of the border posts.

The dominant political group in the north-east region, the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), was against the process and has terse relations with Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki.

When the peace deal was signed, Mr Isaias was highly critical of the TPLF - his nemesis when the countries were officially at war.

When the Ethiopian government attempted to remove military equipment from the border, it was blocked by residents of Tigray who feared future conflict with their neighbour.

Some analysts also blame the slow progress towards peace on Eritrea's President Isaias.

He has resisted opening up his country, considered to be one of the most oppressive on the continent, so he is not pushed into making reforms at home, his critics say.

Have there been democratic improvements?

When Mr Abiy came to power, he freed thousands of political prisoners, ended a state of emergency and unbanned numerous political parties.

He appointed the country's first female president, gave half the seats in his cabinet to women, and committed the country to full multi-party elections in 2020.

These are all measurable democratic gains, but his critics say his leadership style has relied on a cult of personality, while he has sidelined important government ministries from the decision-making process.

Have Ethiopia's internal ethnic tensions got worse?

Tensions between Ethiopia's numerous ethnic communities have always been a matter of serious contention but the authoritarian state had kept a lid on the issue.

When Mr Abiy came to power in April 2018, he introduced wider political freedoms.

In some areas, this has led to open conflict and led some 2.5 millions people to flee their homes in these unstable regions.

A report by Refugees International in November last year criticised the government for encouraging premature returns to regions not yet safe and for not doing enough to protect civilians.

What is Abiy's role as a regional peace mediator?

In his short time in office, Mr Abiy has also played a significant mediation role in other regional hot spots.

He was instrumental in bringing the military regime in Sudan to the negotiating table with the opposition following widespread protests in Khartoum and elsewhere.

The talk led to the formation of a transitional power-sharing government.

In addition, he has tried to help normalise diplomatic relations between Eritrea and Djibouti after years of political hostility.

Mr Abiy has also sought to mediate between Kenya and Somalia in a protracted conflict over the maritime border between the two countries.

And he has been actively involved in peace talks between South Sudan's President Salva Kiir and the rebel leader Riek Machar.

He facilitated a meeting between the two leaders in June last year in Addis Ababa although a peace deal signed last August has yet to be fully implemented.