Nigeria's 'torture houses' masquerading as Koranic schools

- Published

Police say the victims in Daura were subjected to "inhumane and degrading treatment"

The private Islamic boarding school in Daura, northern Nigeria, was not somewhere you would want a child to stay for more than a few minutes, let alone months or years.

The Koranic and Rehabilitation Centre was one of series of institutions raided over the past month where parents have been sending troublesome children and young men who may be addicted to drugs or have committed petty crimes. But the raids have revealed them to be more akin to "torture houses", officials say.

The centre in Daura, President Muhammadu Buhari's hometown, was made up of two main buildings, one clean and well-built where children were taught the Koran.

Across the road was the centre's accommodation - a run-down single-storey compound, made up of five or six dark cells with barred windows and doors around a courtyard.

The students were crammed into unhygienic accommodation that resembled cells

The air was stuffy and nauseating. Former students told us that up to 40 people were kept in chains in each 7-sq-m (75-sq-ft) cell.

Filthy clothes and bedding littered the floor. Those who lived there were often forced to urinate and defecate with their chains on - in the same place they ate and slept.

They would be regularly taken out for beatings or to be raped by the staff.

"It was hell on earth," said Rabiu Umar, a former detainee at the centre.

Life in a Nigerian torture 'school'

Sixty-seven boys and men were freed from the facility. Police said there were 300 people on the school register, but many of them had escaped following a riot the previous weekend.

Over the past month about 600 people have been found to be living in such horrifying conditions: chained, starved and abused.

The first discovery was in late September in the Rigasa neighbourhood of Kaduna city in the north-west. Following a tip-off from a relative, the police found nearly 500 people, including children, detained in appalling conditions.

Videos showed rescued students looking dazed, their legs shackled and their bodies covered in blisters.

People rescued in Rigasa showed signs of being tortured

Some of them were pictured dangling from the ceiling. Others had their hands or feet chained to car wheel rims.

Hafsat Baba, Kaduna state's commissioner of human services and social development, told the BBC at the time the authorities planned to identify all facilities of this type and close them down.

She added that they would prosecute the owners of centres "found to be torturing children or holding people in these kind of horrific situations".

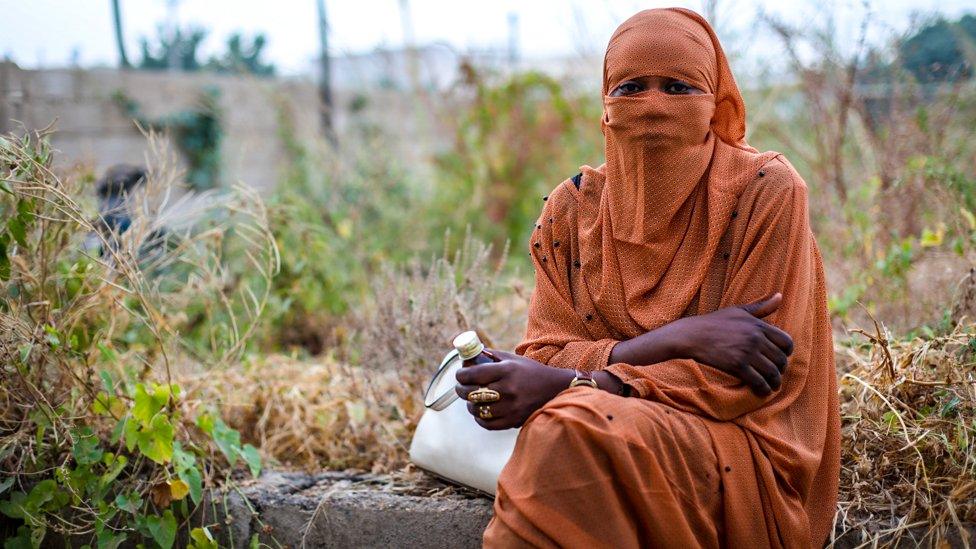

Ten days ago, for the first time women were also amongst those rescued - from another institution in Kaduna.

This is unusual, according to Ms Baba, who added that these institutions seldom admit both sexes.

Women were also amongst those recued from one centre earlier this month

As the raids continue and more details emerge, they have been met with public outrage, but these institutions were no secret.

Jaafar Jaafar, from online media platform the Daily Nigerian, says people who live there have always known.

'Spiritual healing'

"I don't think there is any person who grows up in the north who can claim that they aren't aware of these schools - we all know they abuse children there."

He adds that growing up in Kano in the 1980s and 1990s he was aware of a number of schools like these.

"People believe that these schools have the spiritual power to heal. They don't mind how much the children are dehumanised, or how they're treated, as long as their child receives a Koranic education and is rehabilitated."

You may also be interested in:

However, some parents have denied knowing their children were abused.

Following the raid in Kaduna in September, Ibrahim Adamu, the father of one of the students, told Reuters news agency: "If we had known that this thing was happening in the school, we wouldn't have sent our children. We sent them to be people but they ended up being maltreated.''

According to Sanusi Buba, the Katsina police commissioner, parents are not able to speak to their children while they are at the centres. And even if they visit they do not have unsupervised access to them.

This wave of discoveries has raised awareness outside of northern Nigeria of the problem of abuse in these rehabilitation centres.

Mr Buba said the tradition of people in the north taking their troublesome children to religious rehabilitation centres "has been an age-long situation but [the behaviour] can worsen as a result of abuse".

Nevertheless he is adamant that "the law of this country does not allow someone to create a rehabilitation centre and collect money".

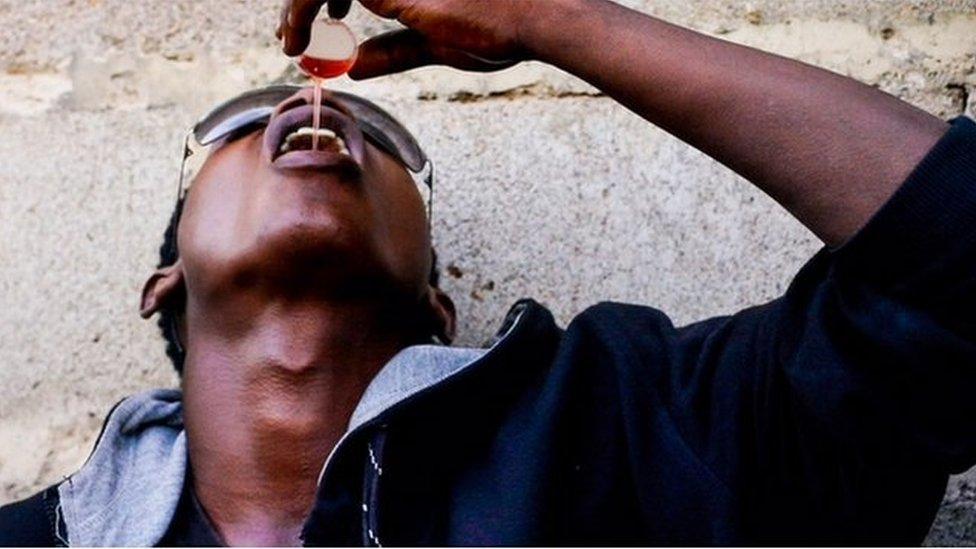

Drug addiction

Part of the problem may be to do with the lack of state-funded facilities in the north.

According to the UN, there were three million drug users in north-west Nigeria in 2017. Nearly half a million of them were in Katsina state, which only runs two rehabilitation centres - one for men and another for women.

Students have been found shackled and chained to car wheel rims

With a lack of publicly-funded options, private rehabilitation centres in the form of these schools have become a final resort for parents who have run out of options.

Even those who manage to access a public facility find conditions are not much better.

Last year a BBC investigation exposed horrifying conditions in a state centre in Kano, where patients with mental health issues were chained to the ground.

BBC Africa investigation: Nigeria’s deadly codeine cough syrup epidemic

Katsina Governor Aminu Bello Masari said his centres were well-equipped to provide the rehabilitation needed for drug abuse or mental disorders.

But with parents still turning to centres that say they rehabilitate people in the name of Islam, it is not clear that the government has the capacity to deal with the problem.

And with no concrete alternatives, desperate families will keep turning to religious centres for solutions.

- Published17 October 2019

- Published29 September 2019

- Published30 April 2018

- Published30 April 2018

- Published28 July 2023