Chalk Back: Kenyan women fight back against street harassment

- Published

Girls in Kibera say they face street harassment on a daily basis

Young women and girls in Kibera, one of Africa's largest informal settlements, are writing their street harassment experiences on roads and canvasses to highlight the damaging nature of sexual harassment.

Warning: Some readers may find part of this article distressing

Zubeida Yusuf has lived in Kibera, in Kenya's capital, Nairobi, all her life, and for as long as she can remember, street harassment has been a part of her life.

"Men will say things like: 'You're very fat. Is your mother a butcher? Did God use his last piece of clay on you because you have large breasts and a big behind.'

"It's a lot for us to take in when we walk out here (in the streets)," says the 22-year-old.

But over time, Ms Yusuf has learnt to fight back and she is helping other women in Kibera claim their voices back in situations where some women say they feel powerless.

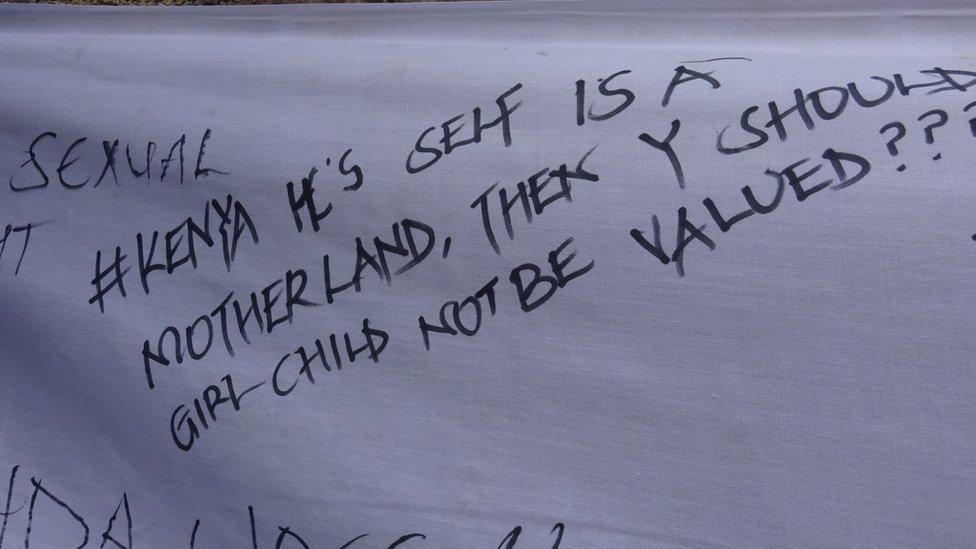

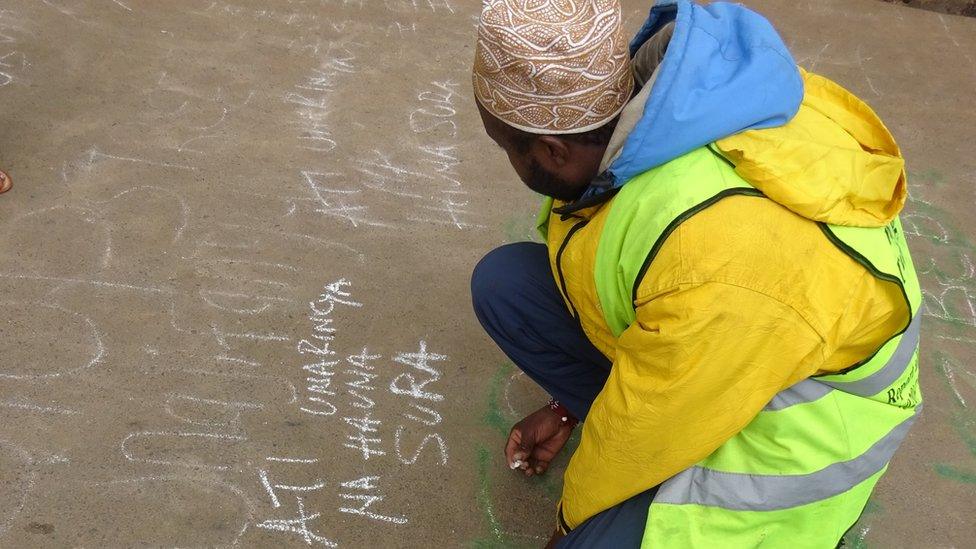

Using chalk and markers, in a campaign dubbed "Chalk Back", Ms Yusuf and other girls and women are writing down their experiences of street harassment.

The campaign, they hope, will spur conversations around the damaging nature of street sexual harassment.

"Nowadays, when the men insult me, I stop and ask them to their faces, why they are insulting me. However, for underage girls fighting back may be harder," she says.

"That's why campaigns like these are important. More of us need to push back and tell people it is not okay to speak to women this way."

Shocking messages

"Respect my body," one message on the road screams.

Others, written in Swahili, reveal more disturbing messages.

The impact of street harassment some girls say can be emotionally distressing

"Unaringa, wewe ni vajo" (You think you are too good for us, yet you're still a virgin).

"Chura hii" (slang for prostitute, which also means frog in Swahili).

Caroline Mwikali, who is 20 years old and also a Kibera resident, confesses some of the slurs used against her have cut deeper than the perpetrators realise.

"You really can't walk down these streets without a man saying something nasty to you. Sometimes we're even likened to animals.

"It affects one's self esteem. When I sit by myself, I wonder: 'Am I really as worthless or as ugly as that person has said I am?'"

Women say rampant street harassment makes them feel unsafe to

But it's not just the emotional cost of street harassment that is the problem.

No-go areas for women

According to the UN, , externalthe lack of conclusive and comparative national data and policies on street harassment within countries is one among many of the challenges when it comes to combating the problem and ensuring the safety of girls and women in public spaces.

A 2019 Plan International street harassment survey of five cities revealed that less than one in 10 of the women and girls, external interviewed reported their experiences to the authorities.

This is because women were unsure of what exactly authorities could do, and whether street harassment could be termed as a "serious" crime.

Experts agree that street harassment continues to curtail women's participation in public spaces, external socially and economically. Often, women are forced to modify their behaviour to fit in.

"There are certain places and scenarios I avoid. When I see a large group of men congregated somewhere, I won't pass there," says Ms Mwikali.

"There are also places, especially in the evening that will never find me outside. Women have been raped in some of these areas."

You may also be interested in:

As the world continues to mark days of activism against gender-based violence, women around the world have been marching to demand more action and justice when it comes to such crimes.

Some men have also picked up the chalk

As Ms Mwikali and other women continue to write on the streets, some men gather around. They confess that the women's revelations of the impact of street harassment has been eye-opening.

"Our mentality for a long time has been that we are entitled to women. We think if we talk to a girl she must talk back. We didn't know that it was not OK until recently. We are slowly learning," says 25-year-old Wilson Maina.

"I think we know better now. We have been enlightened about issues surrounding sexual and gender-based violence and how to deal with it," 26-year-old Jairus Omulando adds.