How Africa hopes to gain from the 'new scramble'

- Published

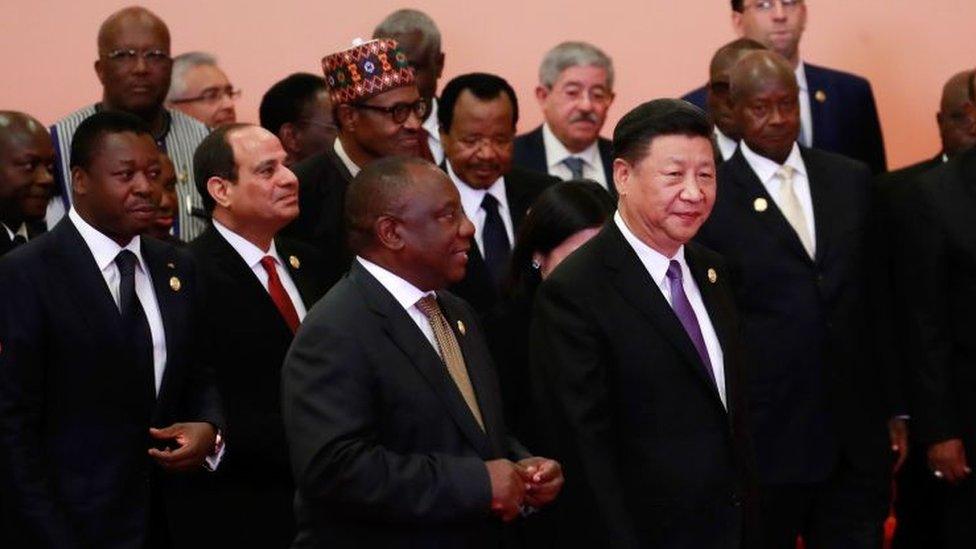

Last year's China-Africa summit attracted the most attendance from African leaders

Major world powers are jostling for political and economic influence in Africa, but what is behind the renewed interest on the continent and what are African countries doing about it? The BBC's Dickens Olewe reports.

In recent years Africans have become used to seeing their leaders accumulate air miles while honouring invitations to attend a series of Africa-themed summits held around the world, often advertised as win-win partnerships.

Last year, Japan, Russia and China hosted African presidents and heads of government; last month 15 African leaders attended the UK-Africa Investment Summit in London, and invitations have probably already been sent for similar events reportedly planned in France, Saudi Arabia and Turkey this year.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

What's the interest?

A mixture of the continent's rich mineral resources, unexploited agricultural land, its influential 54 votes at the UN, stemming a growing threat of Islamist militancy, economic immigration, and anxiety, some say racist, about its burgeoning population, are among the issues behind this renewed interest.

Africa is more than just a continent producing security threats or unregulated migration that must be contained"

"The world needs to engage and help solve Africa's problems, which, sooner rather than later, will become global problems,", external Zambian economist Dr Dambisa Moyo argued in her 2018 article titled: Africa Threat.

"There has never been a greater need for constructive international engagement on the continent. Besides, the global economy could reap significant rewards from positive engagement," Dr Moyo wrote.

Kenya's President Uhuru Kenyatta agrees, saying during a recent visit to the US that Africa is "more than just a continent producing security threats or unregulated migration that must be contained," but that it offers investment opportunities to the world.

However, he warned against the frenzied contest between China, US, Russia, and other countries:

"I have noticed conversations in Western countries and their counterparts in Asia and the Middle East have returned to competition over Africa, in some cases… behaving like Africa is for the taking... Well I want to tell you it is not," Mr Kenyatta added.

Ugandan factory workers assemble mobile phone cases at a factory in Kampala

But does Africa have a plan?

In 2013, African leaders, under the African Union (AU), agreed on a blueprint to tackle the myriad challenges the continent faces. The plan was dubbed Agenda 2063.

It sets out a vision, among others, to end wars on the continent, develop infrastructure, and allow freedom of movement on the continent.

Another flagship project, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCTA), the world's largest free trade pact in terms of countries involved, is projected to improve and boost trade amongst African nations.

Critics, however, say that AfCTA, which comes into effect in July, is not a panacea and faces big hurdles, especially protectionism policies and poor transport infrastructure in member states.

Could free trade deal be a new dawn for Africa?

Flagship projects of Agenda 2063

Connect all African capitals and commercial centres through high speed train network

Accelerate intra-African trade and boost Africa's trading position in the global market place

The development of the Inga Dam in DR Congo to generate 43,200 MW of power

Remove restrictions on Africans ability to travel, work and live within their own continent

Ending all wars, civil conflicts, gender-based violence, violent conflicts and preventing genocide

Establishment of a single African air-transport market (Saatm)

Strengthen Africa's space industry

Create an African virtual and e-university

Develop an encyclopaedia Africana to provide an authoritative resource on the authentic history of Africa and African life

Source: Agenda 2063

However, the AU is struggling to implement Agenda 2063 because the organisation lacks the carrot-and-stick influence to corral member countries to focus on the agreed plans, W Gyude Moore, a former minister of public works in Liberia, says.

He argues that with many African countries increasingly saddled with debt and using their resources to pay off foreign loans, they have been distracted from the grand continental plan.

The state of roads has forestalled economic development in many African countries

He says that they should take advantage of the intensified interest in the continent to find affordable ways of improving the transport infrastructure, especially roads, to help boost their economies.

While the Agenda 2063 makes a big play of high-speed rail, roads are the predominant mode of transport in Africa carrying at least 80% of goods and 90% of passengers, external, according to the African Development Bank (AfDB).

The poor state of the road infrastructure in 49 countries in sub-Saharan African countries has led to isolation of people from basic education, health services, trade hubs, and economic opportunities, the AfDB says.

"Only 43% of the roads in Africa are paved. And 30% of all paved roads on the continent are in one country: South Africa," Mr Moore, who is currently a Senior Policy Fellow at the Center for Global Development in the US, says.

"It's almost impossible to build a modern society and a modern economy without roads," Mr Moore says.

A man washes his motorbike in a flooded road in Liberia's capital Monrovia during the 2014 Ebola outbreak

He gives an example of the 2014 Ebola crisis in West Africa, which happened during the rainy season. "What began as a health crisis was actually an infrastructure crisis," he says.

"Taking the blood specimen from the patient to the lab became invalid because of how long it took," he added.

Mr Moore says that research and investment in building paved roads that can withstand heavy rainy seasons would transform the continent.

You may be interested in:

The Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) is also ambivalent about the Agenda 2063 targets.

Billionaire Mo Ibrahim, IIAG founder, said while reviewing the 2019 index report, that there was a "poverty of data" in measuring progress on the continent., external

"There is no good to set up wonderful targets if you cannot measure them... the African Union agenda has 255 targets, almost half are not quantifiable," he adds.

Another handicap several African countries face is the lack of an effective bureaucracy working in government, Dr Ken Opalo from the Georgetown University told the BBC. Something, he says, democratic African countries can learn from China.

"What makes China succeed isn't autocracy, it's bureaucratic effectiveness... the capacity for making and implementing government policy don't fall in order when you have free elections. It is therefore ridiculous at the moment to expect things to change in countries like South Sudan, CAR or even Malawi," Mr Opalo adds.

The AU admits there have been challenges and it is planning to roll out a platform to enable it to best monitor implementation of the Agenda 2063 targets, the organisation's Vice-Chairperson Quartey Thomas Kwesi, said recently.

"We also welcome criticism," he added.

Creating jobs

Curiously, Africa's most urgent problem, youth unemployment, is not listed as a flagship Agenda 2063 project but according to AU officials, all projects are aimed at creating a conducive environment for job creation.

Africa's population is set to double by 2050 to 2.2 billion, according to projections from the UN population division, putting pressure on governments to create meaningful employment.

African countries are struggling to create jobs for the youth

Another worrying statistic is that while global poverty levels are dropping, they are rising in Africa, according to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The organisation projects that Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo together will be home to 44% of the world's poorest people in 30 years' time if current trends continue.

The agriculture sector which in most countries in Africa offers the best opportunity to lift millions out of poverty is largely untapped and slowed down by lack of investments, Mr Opalo says.

Trapped in desperation and hopelessness, many young people have moved to the cities.

"We now have urbanisation without jobs, and instead of investing in manufacturing we are seeing a lot consumption cities being built. They provide jobs but rely on importation," Mr Opalo says.

It is another multifaceted challenge the continent has to grapple with.

Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel (C) launched the Compact with Africa in 2017 to help encourage private investment on the continent

Dr Moyo asked provocatively in her 2018 article: If the rest of the world never had to hear about Africa again, would anyone care?

The renewed scramble for Africa suggests the answer is yes.

"How Africa's population evolves, and how the continent's economies develop, will affect nearly everything people near and far assume about their lives today, external," Africa commentator Howard French wrote recently.

The challenge is for African leaders to match their rhetoric with achievable and measurable plans, Dr Opalo and Mr Moore say.

They add that the leaders should negotiate policy concessions that match their priorities instead of accepting short-term deals and transactions that are often offered in the now popular Africa-themed summits.

- Published7 May 2020

- Published22 February 2019

- Published2 February 2019

- Published21 March 2018

- Published3 September 2018