Letter from Africa: How London was sold to a child fleeing war

- Published

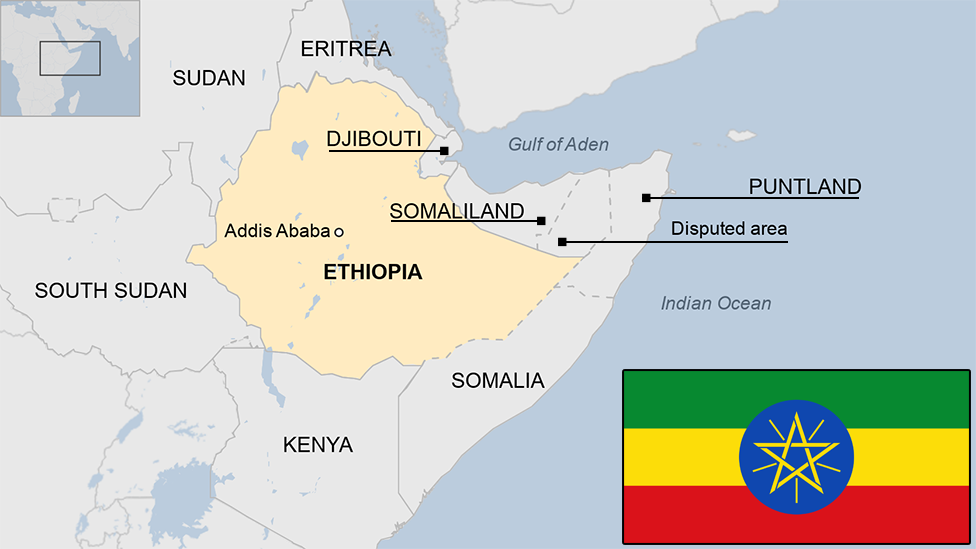

In our series of letters from African journalists, Ismail Einashe reflects on being transported back to his childhood in Ethiopia, and memories of life as a refugee before he moved to the UK.

On a sweltering lunchtime I sat on a small stool drinking coffee and observing life in the Bole-Mikael neighbourhood of Addis Ababa, the heart of the Somali community in the Ethiopian capital.

I had last been here as a young boy in December 1994, where I had lived after fleeing the civil war in Somalia.

Sipping coffee in Addis Ababa's Bole-Mikael neighbourhood sparked a trip down memory lane

My family were forced to leave Hargeisa city in 1988, first escaping on foot to a refugee camp in Ethiopia near the border town of Hartisheik, where I spent the defining years of my childhood and later ended up in Bole-Mikael.

We were not alone.

In the 1990s this neighbourhood became home to a large number of Somali refugees, who had gathered in this dream-filled corner of Addis Ababa hoping to resettle in European countries they knew little about.

Somalis bound for countries like Norway, Sweden, the UK and the Netherlands had come to Addis Ababa waiting for those embassies to make decisions.

The refugee camp near Hartisheik in Ethiopia was once the biggest in the world

As I sipped my coffee and looked around 25 years later, I reflected how radically the area and community had changed - prosperity was in the air.

It was June and people were dressed elegantly in their finest Eid attire for the Muslim festival: women wore bright, beautiful "dirac" robes adorned with gold jewellery while the men wore colourful "khamis" tunics and suits.

The sounds and smells of Eid pervaded the air - spiced goat curries, rice with fried onions and raisins, fudge-like "halwa" sweets and an abundance of sugary soda drinks.

Around me a modern city was taking shape, transformed by new buildings that dominated the skyline some as high as 30 to 40 storeys, covered in bright blue plastic sheets and wooden scaffolding.

Residents of Bole-Mikael were wearing their best clothes for Eid

There were malls everywhere, mobile phone shops, and fast-food restaurants where young couples sat together eating burgers and drinking milkshakes.

But as I wondered through Bole-Mikael's semi-paved side streets, I glimpsed parts of the city I remembered as a child: puddles of dirty water, the incessant barking of dogs, aromas of coffee and berbere spice, young children tugging at my shirt asking for coins.

I have such fond memories of Addis as a child. I remember visiting the Addis Zoo to see the lions and being mesmerised by a portrait of Haile Selassie, the country's former emperor.

'The country with four names'

It all made me think about the past - of how much my family had lost in the war, but how lucky we were to escape and eventually start a new life in the UK.

Looking back now I am not sure if we knew much about where we were going or what we would lose in the journey west.

You may also be interested in

The only thing I knew about the UK was what an elderly Somali woman in Bole-Mikael told me.

She would sit at a street corner for hours a day talking to us children while we drank sodas.

She would ask us where our families were going to.

I told her: "London." She said: "Ah do you know that country has four names? UK, England, London, Europe."

I was intrigued. She also told me that once I got there I would not need to use my legs to walk.

She said there they had machines that did the walking for you - she was, of course, referring to escalators, which back then were in short supply in Ethiopia. I had never seen one.

In London the dangers of Somalia were replaced by a new reality: council estate gangs and social alienation"

When I arrived a few days after Christmas in 1994 at Heathrow Airport I was delighted to see escalators but soon disappointed when I realised that I would have to use my legs on the streets of London after all.

I often wonder if those of us who left Addis in the 1990s knew what we would be giving up - the warmth, safety of language and our land.

But no-one chooses to give up the comforts of home; conflict forced us to make new homes far away.

'Learning to queue'

Yet in countries like the UK we became invisible shadows, cut-off in deprived inner-city neighbourhoods.

In London the dangers of Somalia were replaced by a new reality: council estate gangs and social alienation.

Council estates like this are common in London

Coming to the UK was a huge shock. I felt confused and was unable to make sense of my new home.

I was only 10 and unable to speak English, so I felt like an outsider.

I had a lot to learn and quickly: how to deal with the winters, how to queue, going to school and becoming a citizen in a new culture.

I struggled to fit into British society. Like many of my peers, I came to escape guns, violence and refugee camps and found myself in a rough inner-city neighbourhood, confused and alienated.

There is an air of prosperity Bole-Mikael these days

This experience was often challenging, but as I got older I slowly began to see a world far beyond the small pocket of London I was living in.

I have now lived in London for 25 years and I feel very much at home in this wonderful, diverse and liberal city.

Nevertheless, the walk through Bole-Mikael made me realise how the shadow of Somalia's civil war had remained with me despite having left the conflict behind.

But I understood that as the neighbourhood had changed, so had I.

And I left this time as a man at peace with what I have gone through and become, rather than a fearful child unaware of what life had in store for me.

More Letters from Africa

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

Related topics

- Published2 December 2019

- Published2 January 2024

- Published2 January 2024