Has Felix Tshisekedi tackled DR Congo's six biggest problems?

- Published

When Felix Tshisekedi was sworn in as president of the Democratic Republic of Congo exactly a year ago, it was hailed as a landmark moment - the first peaceful transfer of power in the vast country's almost six-decade history.

For years the country, which has enormous mineral deposits, including a vital ingredient in electric car batteries, had been bogged down by conflict and corruption.

As the flag bearer for the opposition UDPS, Mr Tshisekedi beat his predecessor Joseph Kabila's favoured candidate in the December 2018 vote. But that result was disputed by another opposition candidate, Martin Fayulu, who said he was the rightful winner.

This was not a good start for a leader who hoped to bring together a fractured country facing a host of challenges including an Ebola outbreak, years of fighting in the east, inadequate infrastructure and a struggling economy.

So how has he done on six key issues?

1: Conflict in the east

When he was sworn in, the president pledged to "build a strong Congo, turned toward development in peace and security".

Mr Tshisekedi has tried to boost security but ordinary civilians do not feel any safer than they did 12 months ago.

One his biggest challenges was continued violence in the east of the country, where dozens of armed groups are causing havoc.

The army has gained ground on the battlefield against the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a rebel group that has its origins in Uganda but is now based in DR Congo's Beni region.

But in 2019, the militia intensified revenge attacks against civilians, killing more than 200 people in a three-month period.

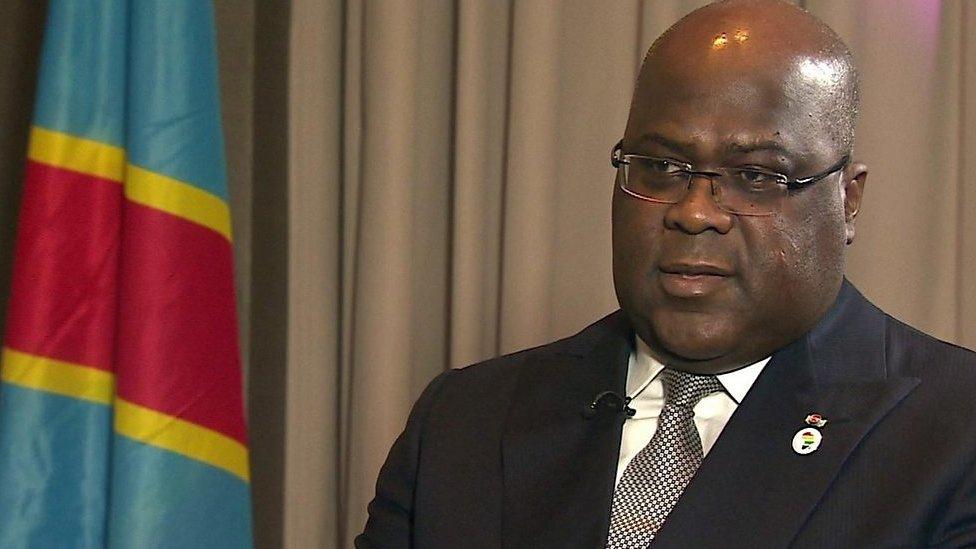

Felix Tshisekedi on his first year in power

"During my election campaign, I had the opportunity to go in these regions and I was struck by this very situation which really hurt me a lot," Mr Tshisekedi told the BBC.

"I made a commitment at that time to do everything I could to bring peace."

The president ordered the army to move a command base to Beni, the city at the centre of the ADF attacks. Some troops have been replaced, bringing new energy into the fight against the militia.

In its battle against another group, at least two key leaders of the Rwandan Hutu FDLR group have been killed.

But many other small armed groups are still active in the region, with some being involved in the illegal trade of minerals.

Attacks on civilians continue, with rebels, armed with nothing more than machetes, able to strike at any time.

The army, meanwhile, has been criticised for trying to fight a conventional war against them.

2: Ebola outbreak

When he came to power, the president was faced with the spread of the Ebola virus, also in the east of the country.

It has since become the world's second worst Ebola outbreak, which the World Health Organization has declared an international health emergency.

since August 2018

3,416infected

2,237died

1,136survived

Mistrust between locals and health workers, fuelled by myths and misinformation, in addition to attacks on members of the Ebola response team, continue to hinder the fight against the deadly virus.

Two vaccines are now being used in the areas affected to prevent its spread.

Mr Tshisekedi's government has had a lot of help from outside agencies and it appears that the rate of new infections is going down, but the WHO says it is difficult to confirm this as there are several areas that are hard to reach because of insecurity.

But the resignation of Health Minster Oly Ilunga last year over a disagreement about how the response was being handled suggested that not everyone in the response team had the same vision of how to fight the virus.

3: Measles outbreak

Mr Tshisekedi has also had to deal with the spread of measles.

The highly contagious virus has infected more than 300,000 people since the start of 2019, with cases being reported in every one of the country's 26 provinces.

At least 6,000 people have died - more than from Ebola - as a result of the epidemic, which the WHO says is the world's worst measles outbreak.

The government, supported by international agencies, have started a large-scale vaccination programme

Mr Tshisekedi's government, supported by the WHO and other international organisations, has vaccinated more than 18 million children under five across the country.

But a lack of funding to buy enough vaccines and poor road conditions have limited the ability of health teams to reach everyone.

The severity of both the measles and Ebola outbreaks are evidence of profound structural problems which have their roots in the long mismanagement of the country, rather than Mr Tshisekedi's time in power.

His government has managed to harness the help of international agencies but he will continue to face enormous challenges in the remainder of his five-year term.

4: Building the country

As soon as he came to power, the president began what he called "the first 100 days emergency programme".

"With very little means [we started] building schools, restoring hospitals, roads, bridges [and] setting up ferries to facilitate river traffic," he told the BBC.

You may also be interested in:

The Congolese NGO Observatory of Public Spending criticised the way the bidding process for contracts was handled.

Furthermore, not many of the projects have been completed and only represent a fragment of the infrastructure needs of the country.

And there is a fear that the extra spending might not actually be used to pay for improved services as the government says.

5: Escaping poverty

Based on average income per person, DR Congo is counted among the five poorest countries in the world, despite its enormous mineral wealth.

Most Congolese live on less than $2 (£1.52) a day, according to the World Bank.

This figure has been steadily growing since the beginning of the century, but the country still has a long way to go.

The president has said he wants to tackle poverty and as part of that effort he has increased government spending.

During the past 12 months, the government budget has risen from nearly $6bn (£4.6bn) to $11bn.

Mr Tshisekedi's supporters hoped that he would improve their circumstances

This has of course opened up the question of how to raise the money.

A popular belief in the president's circle is the money can be found by curtailing government corruption.

But so far, no huge amounts of money have been uncovered and no high-profile figure suspected of corruption has been prosecuted.

The president's spokesperson has said that the justice system is still carrying out investigations.

Taxation in some areas, including on property, have gone up in order to help pay for expenditure.

But most ordinary people remain impatient to see their social and economic conditions improved.

6: Political tensions

Despite winning the presidency, Mr Tshisekedi has had to come to an accommodation with the coalition of his predecessor Joseph Kabila, which controls the majority of seats in parliament.

Negotiations between the two parties took seven months before a consensus was found so that a government could be formed.

Relations between the two parties has been tense over the past year with rival politicians exchanging verbal abuse and in some cases using physical violence.

President Tshisekedi has had to work with allies of his predecessor Joseph Kabila (L)

But there seems to be a determination to make it work.

Since taking power, President Tshisekedi has created a political climate that is in contrast with the last years of Mr Kabila.

Political prisoners have been freed and key opposition figures, who were living in exile have returned to the country, where they are now playing a role without fear of violent repression.

- Published23 January 2020

- Published24 January 2019

- Published2 August 2019

- Published3 November 2019

- Published10 January 2019

- Published31 January