Refugees in South Africa: 'Give us a place where we can be safe'

- Published

Hundreds of refugees and asylum seekers have been crammed into a church in the centre of the South African city of Cape Town for four months. They are desperate to move to another country, as Vumani Mkhize reports.

The air is thick with the smell of too many people confined in one space.

Blankets, making up temporary beds, are strewn all over.

The cacophony of children's playful laughter rises above the scene, but it cannot mask the plight of the more than 500 refugees and asylum seekers who have sought refuge inside Cape Town's Central Methodist Church.

Last October this group, made up of people from across the continent, staged a sit-in protest outside the offices of the UN's refugee agency (UNHCR), demanding to be resettled outside South Africa.

Last October, the police clashed with protesters outside the UNHCR offices in Cape Town

Armed with an eviction order, police tried to forcibly remove them and images of stun grenades and weeping children desperately clinging to their mothers shocked the nation.

At the time the UNHCR said it had been "encouraging [the protesters] to participate in constructive dialogue to address their grievances".

"South Africa is a generous host country with progressive asylum policies and laws," it added.

In their time of need the church offered the group sanctuary. They have remained there ever since.

Nadine Nkurukiye escaped unrest at home in Burundi and has been living in South Africa for 13 years, but has not been granted asylum.

What I'm asking is for the UNHCR to help us, to give us a place where we can be safe"

While in South Africa, a place where she thought she was safe, she was attacked and raped by a man who remains at large.

"There is no help, there is no-one who can show you the way to go," Ms Nkurukiye tells the BBC as she wipes away her tears.

Her voice breaking as she recounts her horrific ordeal, she says her problems are compounded by South Africa's inefficient asylum process, where applicants can spend years waiting for refugee status.

"What I'm only asking is for the UNHCR to help us, to give us a place where we can be safe. Where they can accept us like human beings, because South Africa doesn't treat us like human beings," Ms Nkurukiye says.

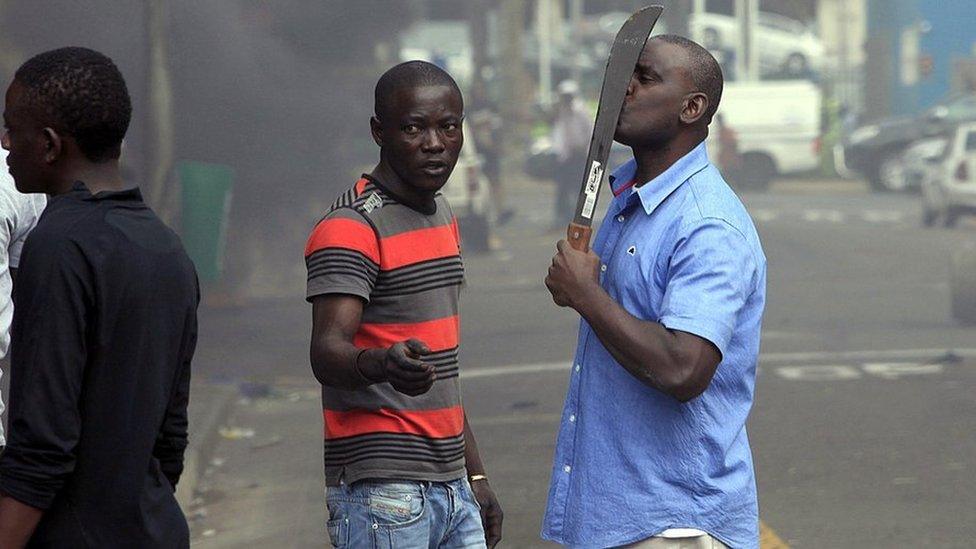

Since 2008, there have been numerous outbreaks of xenophobic violence targeting foreign nationals from the rest of the continent in townships across the country.

Several people have been killed in attacks on migrants in South Africa, as Milton Nkosi reports

South Africa is one of the most unequal societies in the world, with the gap between the rich and the poor growing, and African migrants are caught in the middle of this divide.

They are often targeted in the communities where they live, accused of stealing jobs and resources.

Last year, following a bout of violence, President Cyril Ramaphosa described it as "totally unacceptable" and said there was "no justification for any South African to attack people from other countries".

Refugees in South Africa have to regularly renew their asylum visas at the department of home affairs. Waiting in long queues and faced by documents they do not understand, many have grown weary of the process.

"I've seen clients who have been here for over 10 years... living in limbo, renewing that asylum paper," says Sally Gandar from the charity Scalabrini, which works with migrants and refugees in Cape Town.

"Every one month, every three months or every six months depending on what home affairs decides on the day that you go to get your renewal."

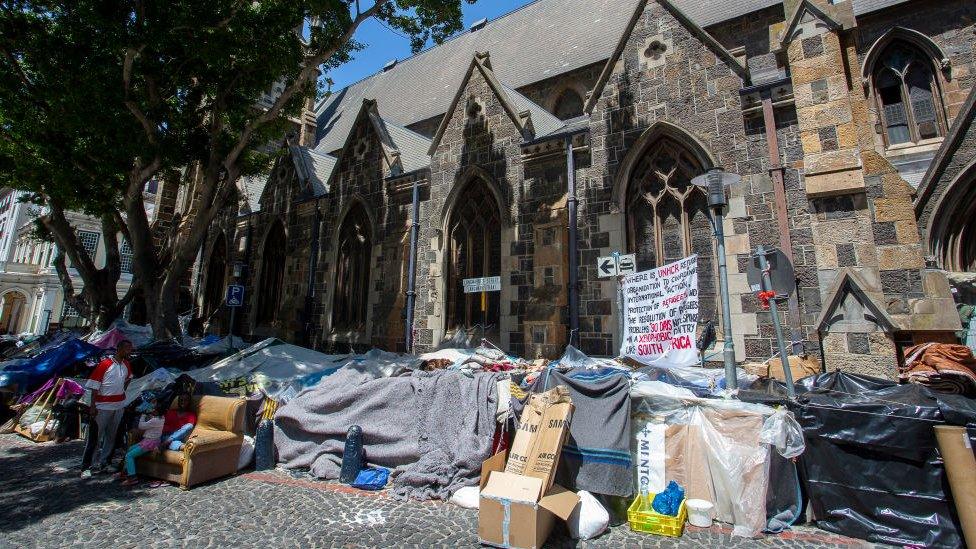

The refugees and asylum seekers have been in the church for four months

The multi-coloured walls and friendly staff of Scalabrini's offices are a welcome relief for desperate foreigners in search of help.

And life has just got harder for refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa. The Refugees Amendment Act is a tough new law that aims to restrict the work refugees can do and prevent them from taking part in political activities relating to their home country.

This has "made it even more onerous and even more difficult for asylum seekers in South Africa," Ms Gandar says.

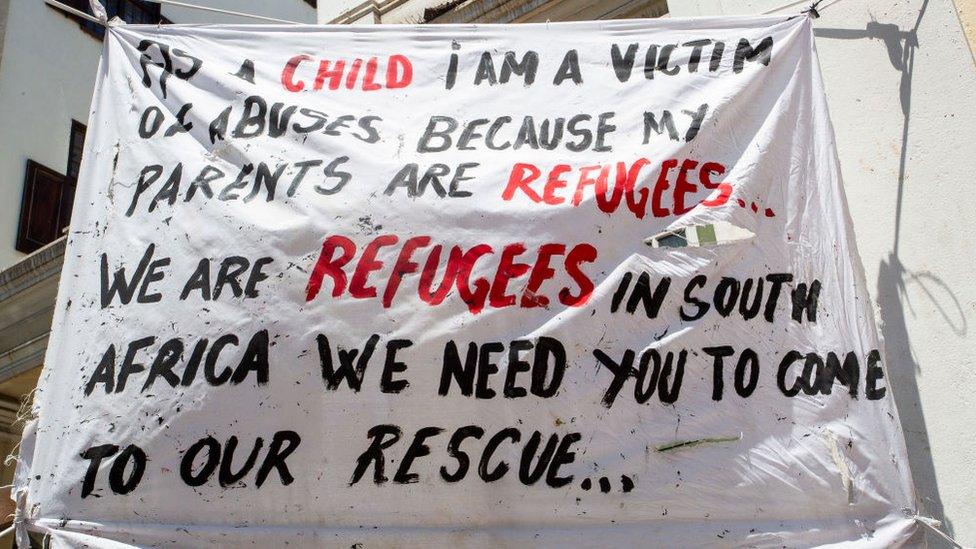

Frustrated with the never-ending asylum renewal process, the refugees want to leave South Africa, with many saying they are also victims of xenophobia and discrimination.

They are demanding that the South African government and the UNHCR resettle them outside the country.

'Irresponsible leadership'

But Chris Nissen from the South African Human Rights Commission believes the group has been deliberately misinformed by their leaders. He says they are aware that the UNHCR does not do group resettlements, opting to evaluate applicants on a case-by-case basis.

"It's very sad, the situation that is there [in the church]," he tells the BBC.

"And of course from a humanitarian point of view it's unacceptable that it continues - children don't go to school. I think it's irresponsible of leadership to allow for that situation to happen, because there's an unrealistic expectation and people are sitting there hoping to be resettled."

Local business owners and residents of Greenmarket Square, next to the church, are growing increasingly impatient.

Locals have been complaining about the temporary homes that have been set up

What should be a popular tourist hotspot resembles a shanty town as makeshift homes made from plastic sheets and cardboard dot the church's exterior.

Children play on the cobbled pavements as their mothers stoke the fires they make to prepare dinner.

Cafe Sante is opposite the church and every morning owner Elias Pazaites says he has to chase away people sleeping in front of his property.

"This has had a huge effect on my business," he tells the BBC.

"All the tour operators don't come here any more and we are just waiting for something to be done. It's lunchtime now, and the place should be full, but as you can see it's empty."

The refugees prepare meals in front of the church

As a consequence he has had to let go some of his staff.

While people in the area were initially compassionate regarding the plight of the refugees, many now want them removed.

"I feel they should just go away, it's not right what they are doing," says angry resident Russell Rass.

"It's affecting the businesses especially, and the people are uncomfortable, so they should go."

'It's not xenophobia'

He was quick to add that he had nothing against people from other African countries.

"We are not xenophobic, we work for our money. We are not xenophobic, it's not right what they are doing, you can't just go and put up camp everywhere around the country, it's just not right."

For the time-being though, the church will continue to provide sanctuary to the refugees, but for how much longer this will continue is not clear.

However, the refugees say they feel unsafe in South Africa's townships and have vowed to remain in the church until they are resettled elsewhere.

- Published2 October 2019

- Published29 August 2019

- Published14 October 2019

- Published21 September 2019