Coronavirus in Africa: Whipping, shooting and snooping

- Published

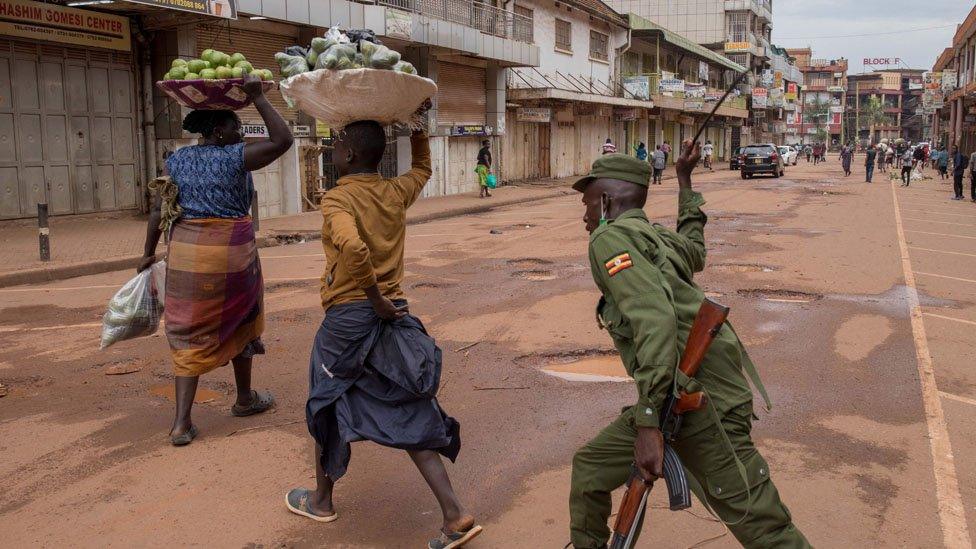

Ugandan police hit vendors who refused to clear the streets

Armed variously with guns, whips and tear gas canisters, security officers in several African countries have been beating, harassing and, in some cases, killing people as they enforce measures aimed at preventing the spread of Covid-19.

The actions of the police and military are at the sharp end of a debate over the balance between personal freedoms and human rights on the one hand, and the need to protect society as a whole from coronavirus on the other.

Faced with a growing health crisis, some African governments have introduced new emergency laws and digital surveillance echoing an earlier and more oppressive era.

Rights groups have warned that if they are not reversed once the crisis is over then these new measures could undermine basic freedoms.

A night-time curfew is in place in Kenya

The authorities say the lockdowns, curfews, and other crowd control measures are aimed at saving lives, but overzealous enforcement has cost lives.

In Kenya, a 13-year-old boy playing on a balcony in a high rise residential building in the capital, Nairobi, was shot dead after being hit by what police described as a "stray bullet".

Three other deaths, including that of a motorcycle taxi rider who succumbed to injuries after being beaten by police, have been reported in the local press.

President Uhuru Kenyatta has apologised "to all Kenyans… for some excesses which were conducted" by the security forces, while urging the public to abide by measures the government had put in place to contain the spread of the virus.

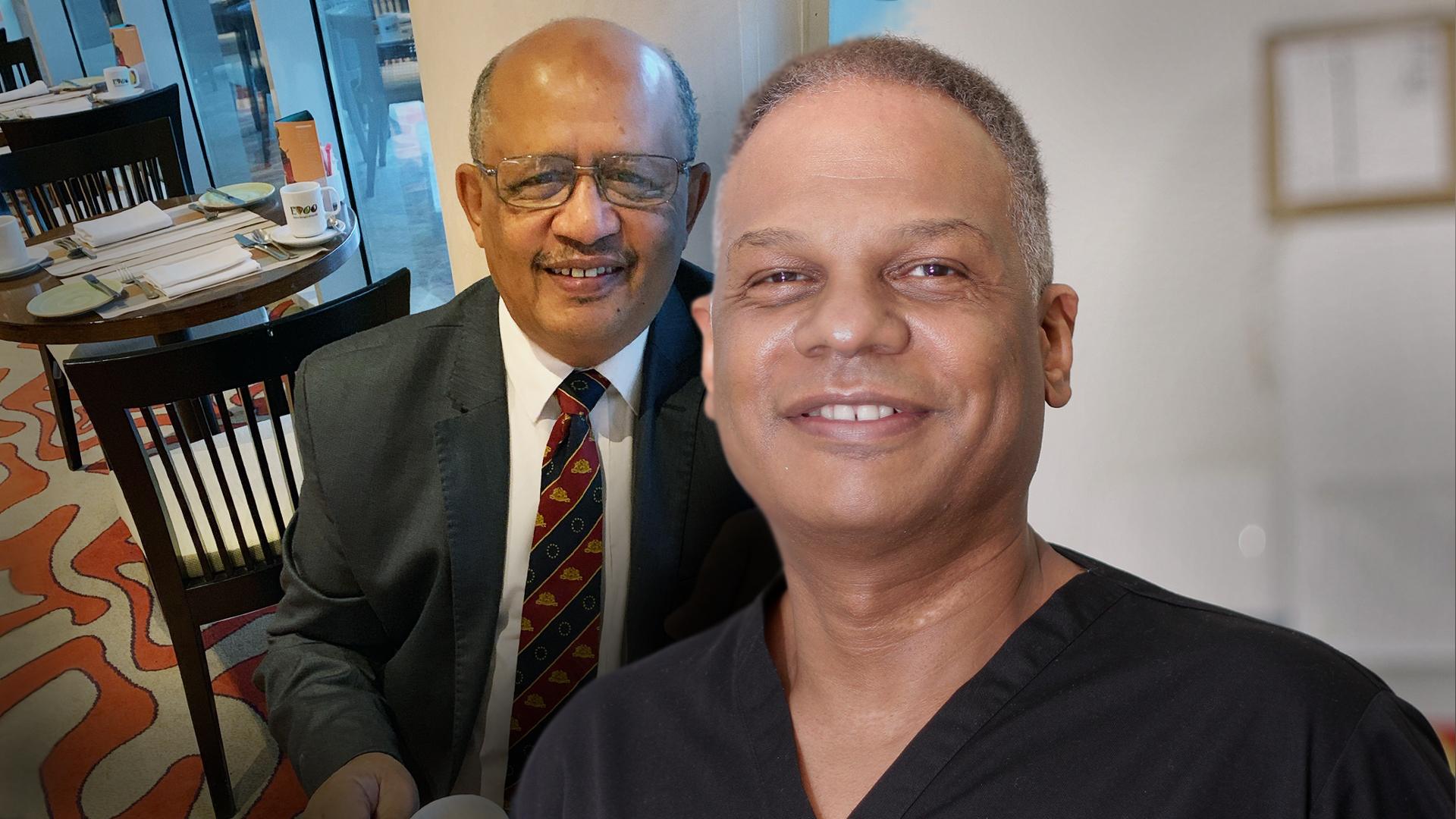

'Gays targeted in Uganda'

In neighbouring Uganda, Human Rights Watch (HRW) has accused police of using "excessive force" - including beating fruit and vegetable sellers and motorcycle taxi riders.

Moreover, police arrested 23 people during a raid on a shelter for homeless lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth, accusing them of disobeying orders by remaining in the shelter and charging them with "a negligent act likely to spread infection of disease", HRW said.

The police and army have been deployed in South Africa to enforce a lockdown

"The basic human rights of people should be at the centre of the government's response to this pandemic, especially those who are most vulnerable like street vendors, and homeless youth," HRW said.

In the face of mounting criticism, 10 officers were charged with torture on Tuesday after being accused of caning 38 women and forcing them to swim in mud in the northern town of Elegu. The officers have not yet been asked to plead.

While in South Africa, which has recorded the highest number of Covid-19 cases on the continent, at least eight people have been killed by police since a nationwide lockdown was imposed on 26 March, the country's Independent Police Investigative Directorate said.

'Loaded gun'

Nearly all countries on the continent are battling the spread of coronavirus, and with confirmed cases surpassing 10,000, there are legitimate reasons to be worried about the disease.

Most have poor healthcare systems that could be overwhelmed, resulting in an unprecedented health disaster.

However, global watchdog Freedom House has warned that some measures being used to fight Covid-19 could have lasting "harmful effects and can be extended and re-purposed after a crisis has passed".

Coronavirus in Lagos: Enforcing the lockdown in Africa's biggest city

Opposition groups in Ghana are, for instance, worried about a new law that gives the president sweeping powers to impose restrictions on people's movements.

"We wanted the president to use emergency powers in the constitution which would require him to come to parliament every three months so that MPs can assess if the measures are needed," Ras Mubarak, an MP for opposition National Democratic Congress, told the BBC.

"The new law gives him a loaded gun to use as he pleases, especially in restricting people's movements."

Ghana's Justice Minister Gloria Akuffo defended the legislation, saying it had been drafted to protect the nation's health and would help deal "not only with the risk that our country has been exposed to presently but also in the future".

'Perfect timing'

Similar concerns have been raised in other countries.

Critics of Malawi's President Peter Mutharika say he is using the coronavirus outbreak to "fix his political problems".

The government is happy with the coronavirus status and want to use it as a scapegoat to continue the president's rule"

"The government would want to use coronavirus to prolong their stay in power," Gift Trapence, the leader of the Human Rights Defenders Coalition, told the BBC.

Mr Mutharika, who in July is facing a re-run of last year's annulled election, has declared a state of national disaster.

The new powers allow him to ban public gatherings.

"They are happy with the coronavirus status and want to use it as a scapegoat to continue the president's rule," Mr Trapence said.

Malawi's Information Minister Mark Botomani dismissed such comments as "the usual noise" from civil society groups.

"Our focus as a government is to put everything in place to protect the lives of our people," he said.

You may also be interested in:

In Africa's second most-populous country, Ethiopia, a state of emergency has been declared following the indefinite postponement of the much-awaited August election because of coronavirus.

Nobel Prize-winning Prime Minister Ahmed Abiy says he held discussions with opposition leaders on his response plans for the pandemic after some hit out about not being consulted about the poll delay.

Yet it has not eased their fears, with the Oromo Federalist Congress saying the state of emergency should not be misused.

Ethiopia, the second most-populous state in Africa, has declared a state of emergency

Tahir Mohammed, from the National Movement of Amhara, said the decree was too vague and people had "a right to know what was allowed and what was prohibited".

"What we're seeing is that the government is still focusing on activities that have political gains - it's showing a tendency to do politics even now," he told the BBC.

Though Isabel Linzer from Freedom House says when it comes to the vote, a postponement is not a bad idea.

"It may allow time to better prepare and administer a more credible election," she told the BBC.

Magufuli criticised

Another development that rights groups are concerned about is the targeting of people who challenge the official narrative about the health pandemic.

In Tanzania, the Communication Regulatory Authority (TCRA) penalised three TV stations for airing content that was "misleading and untrue" about the government's strategy on fighting coronavirus.

The TCRA did not elaborate, but speculation is that it objected to a report which criticised President John Magufuli for saying that churches should remain open because "coronavirus cannot survive in a church".

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

Ten journalists covering the impact of Uganda's lockdown were beaten by security officers, Robert Sempala, from the Human Rights Network for Journalists in Uganda, told the BBC.

While the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has singled out South Africa's new regulation criminalising the spread of misinformation for criticism.

"If information is false, it needs to be debunked instead of criminalising speech," the CPJ's Muthoki Mumo told the BBC.

Mobile phone tracking

Privacy rights are also a cause for concern for some.

Activists says people should be informed if they are being tracked via their mobile phone

The authorities in Kenya have been tracking mobile phones of people suspected to have Covid-19 as a way of enforcing a 14-day mandatory isolation period, government spokesman Cyrus Oguna told the BBC.

"We want to know that they are where they say they are," Mr Oguna said, adding that a mobile app was being developed so that "detailed" information about their movements could be obtained.

Kenyan lawyer and privacy specialist Mugambi Laibuta said that while freedoms were not absolute, people should be informed that they were being tracked and how their data was being handled and stored.

South Africa is also working with mobile phone companies to collect geo-location data from mobile phone towers to help track people who had contact with Covid-19 patients.

However, the government has stressed that it is not intercepting calls.

There's certainly a place for certain kinds of medical surveillance right now, there's no question about that"

The UN special rapporteur on freedom and rights, David Kaye, said it was understandable for governments to use emergency measures to deal with the health crisis.

"There's certainly a place for certain kinds of medical surveillance right now, there's no question about that," he told the BBC.

To avoid the abuse of power, all new regulations should be subject to judicial oversight, and have a sunset clause so that they did not remain place after the Covid-19 crisis, he added.

South Africa has taken a step in this direction, appointing a respected former judge, Kate O'Reagan, to oversee the use of data, and to recommend any changes required to the emergency regulations.

Activists welcomed the move, but said the public needed to remain vigilant.

"I think that we must always have reservations [about surveillance] and that it's good to stay sceptical about these things, external," South African digital rights activist Murray Hunter said.

- Published8 April 2020

- Published4 April 2020

- Published24 April 2020

- Published2 April 2020

- Published26 March 2020

- Published29 March 2020

- Published4 April 2020