How do you fight a locust invasion amid coronavirus?

- Published

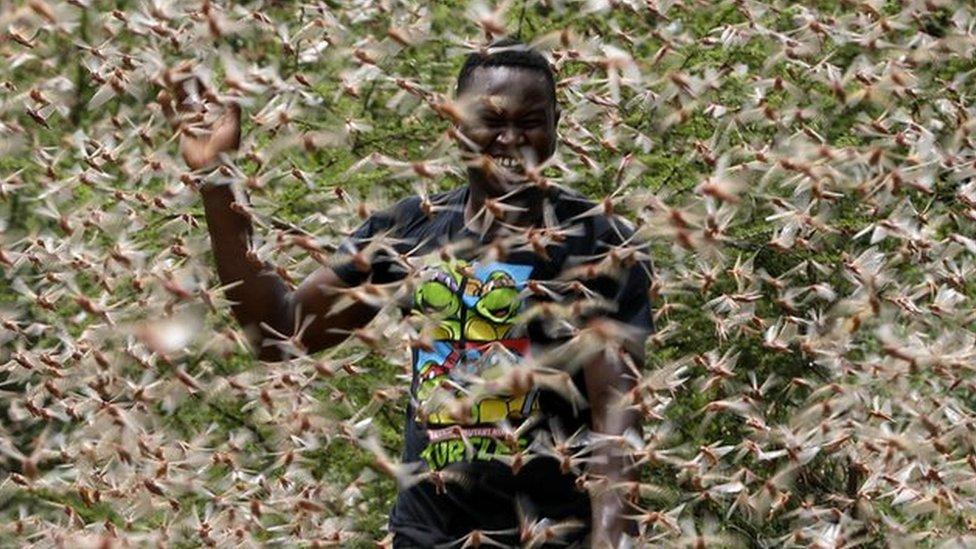

A second invasion by desert locusts has hit East Africa in just a few months, as younger and more aggressive swarms hatch and spread across a region already battling hunger and coronavirus, which has made it more difficult to get supplies to kill the crop-devouring pests.

Currently, Africa's second most-populous state, Ethiopia - along with regional economic powerhouse Kenya and politically unstable Somalia - have been worst hit.

The UN estimates the swarms could be up to 20 times bigger than during the first invasion -and they could become 400 times bigger by June.

"We found locusts on bushes, on pasture, irrigation plantations, even in forests," said Meseret Hailu, an Ethiopian government official who assessed the devastation caused by the latest invasion in the country's northern Amhara region.

The staple grain teff - along with vegetables such as onions - have been devoured by the pests, she added.

Usuallylead shy, solitary lives

Whenthey get crowded together they become gregarious mini-beasts

Colourchanges from brown to pink (immature) and yellow (mature)

Swarmcan be the size of Paris or New York

40 million eat the same amount of food daily as three million people

Cropsare destroyed and livelihoods threatened

Towards the end of 2019, a major upsurge of swarms was seen in Ethiopia, as well as its neighbours Eritrea and Djibouti, and continued to spread, taking hold in Somalia, Kenya and even reaching Uganda, South Sudan and Tanzania though in smaller numbers.

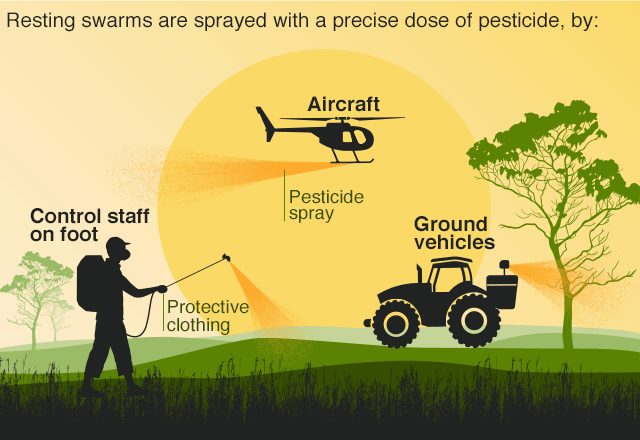

Governments, which have not been confronted with such large invasions for at least a quarter of a century, have had to scramble for pesticides, protective clothes, fumigators and aircraft to fly above the locust swarms, and spray them dead.

"The scale-up of the operation has been the biggest difficulty," said Cyrill Ferrand from the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

"That first generation reproduced then laid eggs on the ground, and then we have this second generation that is now maturing."

Locust swarms are adding concerns to food security in Africa during the pandemic.

The younger creatures are much more aggressive in devouring vegetation. These swarms are now reported to be spreading along the borders of Kenya and Somalia and into Ethiopia.

By the start of April, they began to fly into Uganda once again - a local official estimated that just one swarm was spreading across five sq km (1.9 sq miles).

Mass breeding in Kenya

The short rainy season from February to May is the perfect time for farmers to plant their seeds in the ground in the hope of a bumper harvest in June.

Following the droughts of recent years, there have been good rains this time. But the moist, humid conditions are also perfect for locust eggs to hatch.

Northern and central Kenya are not a traditional habitat for the pests. The country has not experienced a major upsurge for more than 70 years but farmers are witnessing the mass breeding of locusts.

Jude Musili Mkulima, who lives in the town of Mwingi in central Kenya, is worried things will only get worse.

"The mother locusts came and left eggs. After two weeks now, they have already hatched. They are millions more than their mothers. These small ones are eating everything, even pastures for our cows," said Mr Mkulima, echoing the words of Ms Meseret in Ethiopia.

Pilots need quarantine

To bring the invasion under control, pesticides and the more environmentally friendly bio-pesticides are needed. They are sourced from countries such as Japan, the Netherlands and Morocco.

But with the coronavirus pandemic grounding most flights, cargo supply chains have become less reliable and more expensive.

Find out more about locusts:

"It has slowed down importations. And when you are late with spraying, you know the consequences - the insects will increase. That situation has particularly hit Kenya," said Dr Stephen Njoka, the executive director at the Desert Locust Control Organisation for East Africa.

Helicopters needed to track the locusts movements have also faced delays getting into the region - a shipment from Canada has not arrived yet - and pilots have to undergo quarantine when they arrive.

Protective clothes for fumigators - including overalls, boots, goggles and masks similar to those worn by teams disinfecting streets and other public places to curb the spread of the virus - come mainly from China.

UN FAO regional spokeswoman Judith Mulinge said they currently had enough stocks, but were concerned about running out if delays in deliveries persist.

Ugandan soldiers have helped to curb the locust invasion

The UN predicts if the outbreak is not brought under control soon, the size of swarms could grow 400 times by June, affecting mid-year harvests.

"When the plants are emerging, desert locusts are going to eat into these very young plants, which means that all the effort to grow crops will be vanished. We could have people with zero harvests, up to 100% losses," said Mr Ferrand.

In one of the worst-hit countries, Ethiopia, the insects devoured about 200,000 hectares of cropland and more than a million hectares of pasture.

The FAO estimates that about one million people in the country have already been pushed into hunger by the locust infestation.

This worries regional experts, who point out that hunger caused by the infestation - along with lockdowns in place because of coronavirus - could have a devastating effect on poverty levels.

Jasper Mwesigwa, a food security analyst with the regional inter-governmental body Igad, said that 25 million people in the eight states that make up the group were currently struggling to feed themselves and a further five million could be threatened by hunger if the locust invasion was not contained.

"That would be the highest number of food insecure people this region has had," he added.

- Published10 March 2020

- Published2 February 2020