Cameroon's deadly mix of war and coronavirus

- Published

Prominent Cameroonian human rights activist Beatrice Titanji leapt for joy when a major secessionist group declared a ceasefire on 29 March to protect people from the "fury" of coronavirus in the central African state's English-speaking heartlands, but her hopes have since been dashed as fighting continues to rage.

"It's a scary situation. Thousands are trapped in the bushes," Dr Titanji told the BBC.

"How do we tell them about Covid-19?" she added.

The Southern Cameroons Defence Forces (SCDF) unilaterally declared the ceasefire, following an appeal by UN chief António Guterres for conflict to end across the world.

"The fury of the virus illustrates the folly of war," he said.

"It is time to put armed conflict on lockdown and focus together on the true fight of our lives," Mr Guterres added.

Cameroon's descent towards civil war

However, none of Cameroon's other secessionist groups, estimated to number at least 15, have heeded the appeal.

The Ambazonia Governing Council, which is one of the biggest groups, said a unilateral ceasefire would open the way for government troops to march unopposed into territory under its control.

Hunger and illness

Cameroon's government, led by the French-speaking President Paul Biya, has not declared a truce either and, to the dismay of aid workers, has banned humanitarian flights, along with commercial flights, in its efforts to curb the spread of the virus.

"If we don't have the means to reach out to people and give them food and medication, many of them are going to suffer. They will die of hunger and illnesses," said Dr Titanji, an academic who leads the Women's Guild for Empowerment and Development, a non-governmental organisation involved in peace initiatives in Cameroon.

Both English and French are official languages in Cameroon following a complicated colonial history but in practice, the Francophone majority dominates, leading the Anglophone minority to complain of discrimination.

About 3,000 people have already died since protests over the increasing use of French in courts and schools in the English-speaking heartlands of the North-West and South-West regions morphed into violence in 2017.

Nearly a million people have also been displaced by the conflict - many of them fled into bushes, where they built huts and villages as they started life afresh after their once-peaceful cites and towns turned into battle zones.

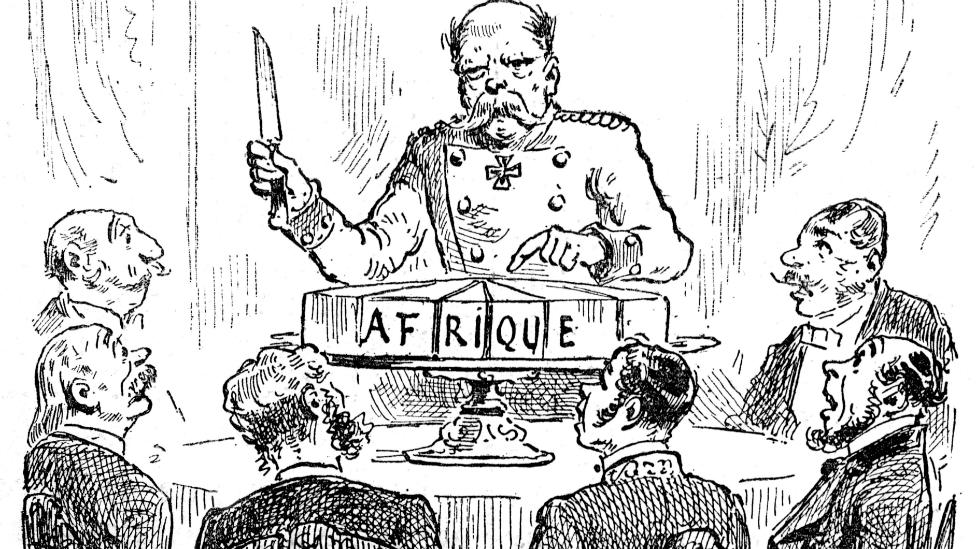

Cameroon - still divided along colonial lines:

Africa's borders were "carved up" up by colonial powers

Colonised by Germany in 1884

British and French troops force Germans to leave in 1916

Cameroon is split three years later - 80% goes to the French and 20% to the British

French-run Cameroon becomes independent in 1960

Following a referendum, the (British) Southern Cameroons join Cameroon, while Northern Cameroons join English-speaking Nigeria

Read more: Cameroon timeline

The UN children's agency, Unicef, estimates that about 255 of the 7,421 health facilities in the North-West and South-West are either non-functional or only partially functional, external because of the conflict.

Some of the facilities have been attacked and burnt down, forcing medics to flee.

This has increased fears about treating people in the event of a major outbreak of Covid-19.

We don't need war at this time, with Covid-19 raging and killing people"

Cameroon has so far recorded more than 2,200 cases and 100 coronavirus-related deaths since March, the highest in central Africa.

However, few of them have been in the North-West and South-West, either because of little testing or because conflict has heavily restricted movement, effectively putting many urban and rural areas on lockdown long before the outbreak of coronavirus.

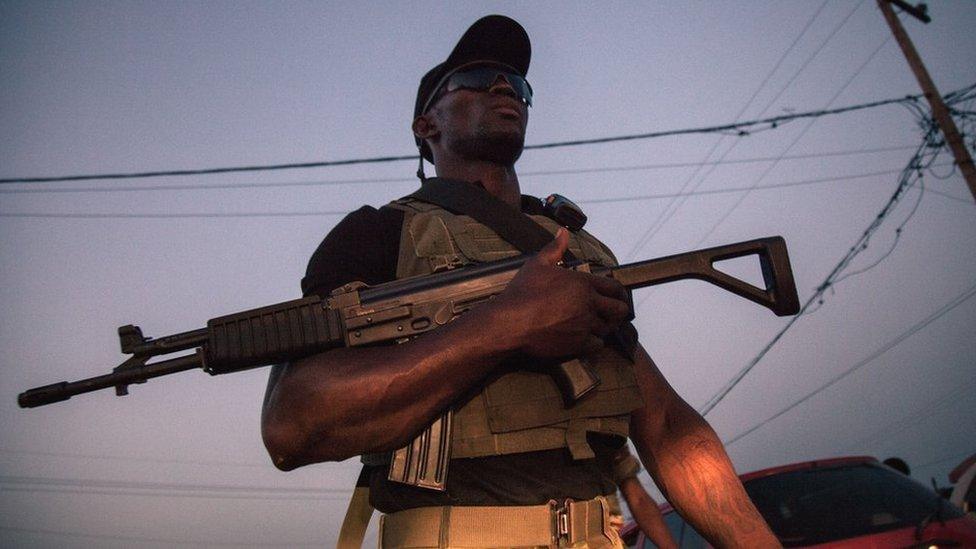

Like most civilians, soldiers are now seen wearing mass-produced protective masks, and using hand sanitizer, as they patrol cities and towns in the North-West and South-West.

Many people have lost their properties and livelihoods because of the conflict

However, there is little indication that the armed militias have taken any protective measures against coronavirus, or that they are medically equipped to deal with infections in their forest hideouts - where they sometimes hold abducted government officials.

About 300 government troops carried out a six-day operation against the separatists late last month. The military said it had killed 15 fighters, and destroyed two of their military camps outside the town of Bafut in the North-West.

The security forces are still searching for three government officials, including a court registrar, after they were seized by separatists in Boyo, another town in the North-West, late last month.

Lamenting the continuing conflict, Dr Titanji said: "It's a great challenge getting aid to the suffering masses. We don't need war at this time, with Covid-19 raging and killing people."

More about the secessionist crisis:

- Published21 May 2013