Libya conflict: Russia and Turkey risk Syria repeat

- Published

The conflict has denied Libyans access to a decent life despite its oil and gas riches

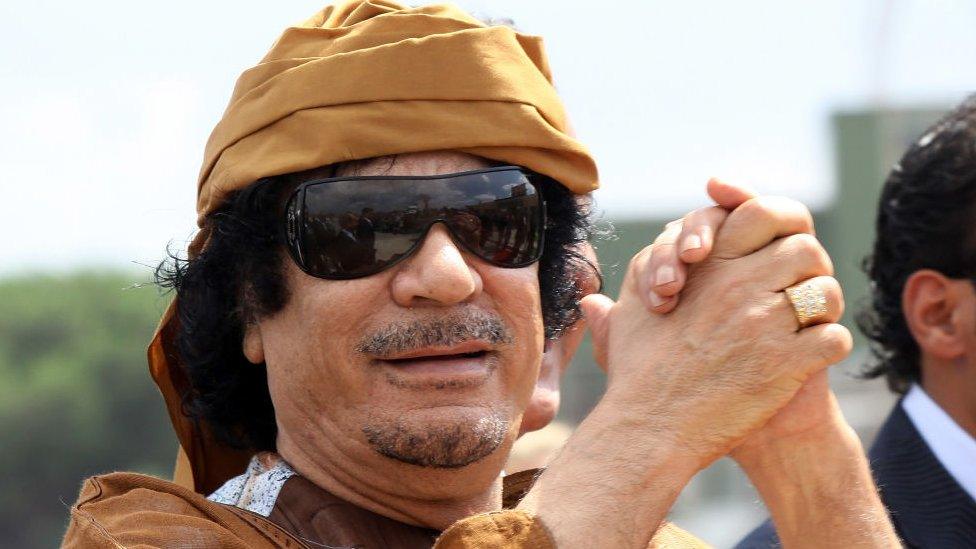

Libya looks to be at the end of one bleak chapter, but there is no guarantee that the next will be any better for a country that has been torn to pieces by civil war and foreign intervention since Col Muammar Gaddafi met his grisly death in 2011.

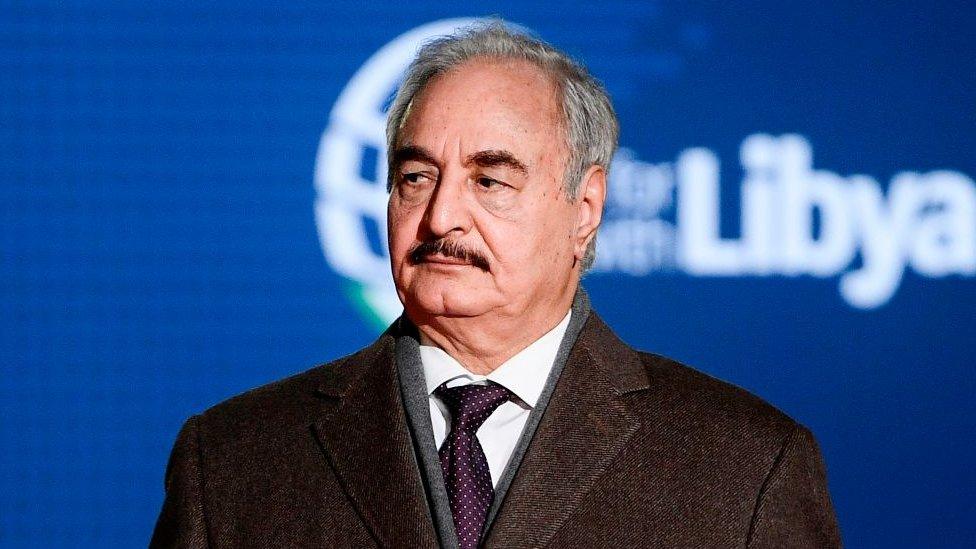

Since last year Gen Khalifa Haftar, the strongman of eastern Libya, has been trying to capture the capital, Tripoli, in the far west of the vast country.

Intervention by Turkey in support of the Tripoli government, recognised by the United Nations, looks to be decisive. Gen Haftar's men, along with a force of several thousand Russian mercenaries, are in retreat.

But that does not mean that Libyan civilians can expect the peace they crave. Once again they are the biggest losers.

Their country, richly endowed with oil and gas, should be able to guarantee them rights of which they can only dream: education; healthcare and a decent standard of living. They don't have any of them, or safety.

What's behind the fight for Libya?

Libyans who have not lost their homes have been locking down to prevent the spread of Covid-19, hoping they do not also become the target of artillery, drones or warplanes. The war has destroyed most of Libya's clinics and hospitals.

Around 200,000 civilians in western Libya have already been displaced from their homes, according to Hanan Saleh of Human Rights Watch.

Libya's future once looked bright

In a recent webinar organised by the think-tank, Chatham House, Ms Saleh said that "you have to look at Libya currently as an accountability-free zone and it has been that way unfortunately since 2011".

All parties in the war have been reckless in their treatment of civilians, though Gen Haftar's side, she said, has committed more documented abuses that could potentially be crimes of war.

Fighters loyal to the UN-backed government have pushed back Gen Haftar's forces recently

It is hard to believe now, but after Col Gaddafi was overthrown it looked for a while as if Libya might have a decent future.

Back in 2011 I walked with the British ambassador through the ruins of his embassy in Tripoli; it had been attacked and torched by a mob after Nato started bombing the Gaddafi regime's forces.

Next to the charred frame of what had been a 1920s billiard table, we talked about the pride that Libyans had in their revolution, their luck in not being cursed with significant sectarian differences like Syria or Iraq, and about the treasure house of oil and gas under the vast Libyan desert.

Perhaps even tourism would be possible. Libya has 2,000 kilometres of Mediterranean beaches, and Roman archaeological sites that are the equal of anything in Italy.

But Libya was broken, and in almost a decade since that conversation it has continued to fragment.

You may be interested in:

The militias that took on the Gaddafi regime never disbanded, and came to like their power.

Once the colonel, his sons and the family's cronies were gone, no kind of functioning state was left. The men who acquired the important job titles found that if there were any levers of government to pull, they came away in their hands.

Libyans who saw themselves as revolutionaries were in no mood to ask for much help from the powerful countries which had provided weapons and most importantly an air force to help them win.

In turn, the outsiders were relieved to be able to turn away, declaring the job was well done. Removing Gaddafi was one thing. Helping to build a country was something very different.

It did not take long for the remains of Libya to fall into even smaller pieces. The bigger towns became city-states.

The militias had their own agendas and would not lay down their weapons. A series of diplomats, mostly under the auspices of the United Nations tried, unsuccessfully, to promote dialogue and reconciliation.

Foreign powers seek Libya prize

By 2014 Gen Haftar had emerged as a power in the broken land, expelling radical Islamists from Benghazi, Libya's second city and the capital of Eastern Libya.

Gen Haftar was well known in Libya, as a general who had fallen out with Gaddafi. In exile he had spent years plotting Gaddafi's downfall from a new base in Langley, Virginia - the American town that is also the headquarters of the CIA.

Libya, in reality already in pieces, eventually found itself with two rival governments.

Gen Haftar controlled the east from Benghazi, and set about unifying the country by marching west to attack Tripoli, the capital, aiming to unseat the internationally recognised Government of National Accord led by Fayez al Sarraj.

Who controls Libya?

Supporting Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj (l)

Turkey

Qatar

Italy

Supporting Gen Khalifa Haftar (r)

United Arab Emirates

Jordan

Egypt

Russia

France

It was certain that foreign powers would get involved in the civil war. Libya is a desirable prize. It has the biggest reserves of oil and gas in Africa, with a population of less than seven million.

Strategically, it is opposite Europe and its hydrocarbons can be exported direct to markets in the west through the Mediterranean. Rival producers in the Gulf need to ship their exports through potentially dangerous sea lanes.

Gen Haftar's most important backers are Russia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt.

Turkey is the key ally of the Sarraj government in Tripoli.

The US has sent a variety of signals out about Libya under President Donald Trump, offering encouragement at different times to Mr Sarraj and Gen Haftar, and bombing jihadist extremists when they can find them.

Now their biggest concern is that Russia's President Putin might be establishing himself in Libya in the same way that he has dug into Syria.

Libya's war has developed disturbing similarities with Syria's. The arbiters of the fate and future of both are the same foreigners.

The proxy wars in Libya have become, in many ways, a continuation of the proxy wars in Syria. Both sides have flown in Syrian militias to apply the skills they have gained in almost a decade of war in their homeland.

It is possible that Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Russia's President Vladimir Putin have applied in Libya a version of the deals they have made in Syria.

The Russian mercenaries who have fought with Gen Haftar are from an organisation known as the Wagner Group, run by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a close associate of President Putin. The Wagner fighters have also been used in Syria.

It is significant that the Russian pullback from Tripoli has not been harassed by Turkey's highly efficient military drones. The Russians have also moved advanced warplanes into Libya.

The next big battle

President Putin and President Erdogan could have agreed to end Gen Haftar's offensive against Tripoli so they can split the spoils between them, according to Wolfram Lacher, a German academic who has just published a book about the fragmentation of Libya.

In the Chatham House webinar he said: "We are talking about two foreign powers trying to carve up spheres of influence in Libya and their ambition may well be for this arrangement to be long term."

He doubted whether the other powers involved in Libya, and the Libyans themselves, would quietly accept the arrangement.

The influence of Libya's late leader Muammar Gaddafi can still be felt in the ongoing conflict

The next big battle could be for Tarhuna, a town that lies around 90km (55 miles) south-east of the capital.

It is Gen Haftar's western stronghold, controlled by a militia known as al-Qaniyat, mainly made up of men previously loyal to the Gaddafi regime.

Troops loyal to the Tripoli government, former opponents of Gaddafi, are advancing on Tarhuna.

The fight against the old regime is still a factor in Libya's never-ending war.

- Published7 May 2020

- Published23 January 2020

- Published8 April 2019

- Published23 February 2018