Algeria's lessons from The Plague in the age of coronavirus

- Published

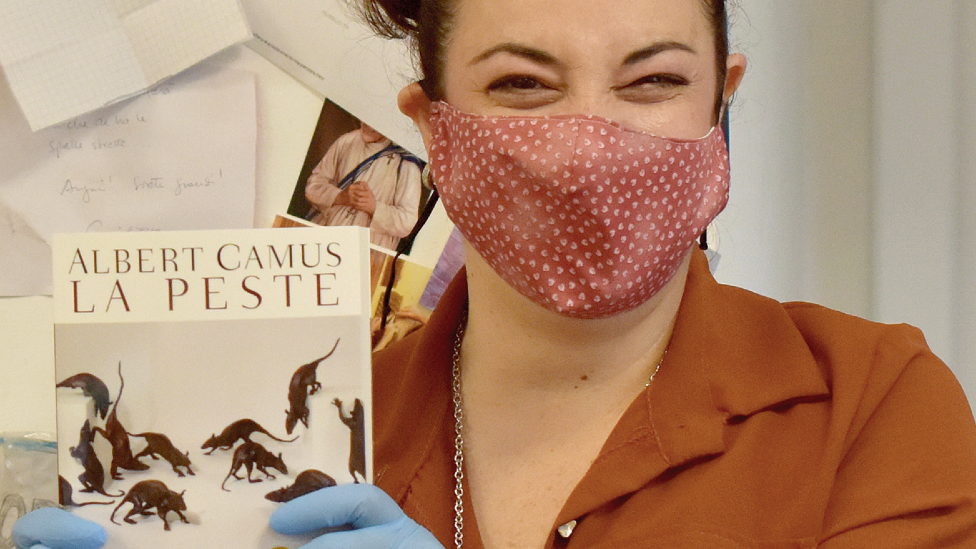

The Plague has been flying off bookshop shelves worldwide

The Mediterranean city of Oran was the setting for a famous fictional outbreak of bubonic plague in Algeria under French colonial rule. The BBC's Lucy Ash finds parallels between Albert Camus' novel The Plague and how the country is coping with the coronavirus pandemic amid political upheaval.

Although it was published 73 years ago, today The Plague almost feels like a news bulletin. It has been flying off bookshop shelves around the world as readers struggle to make sense of the global spread of Covid-19.

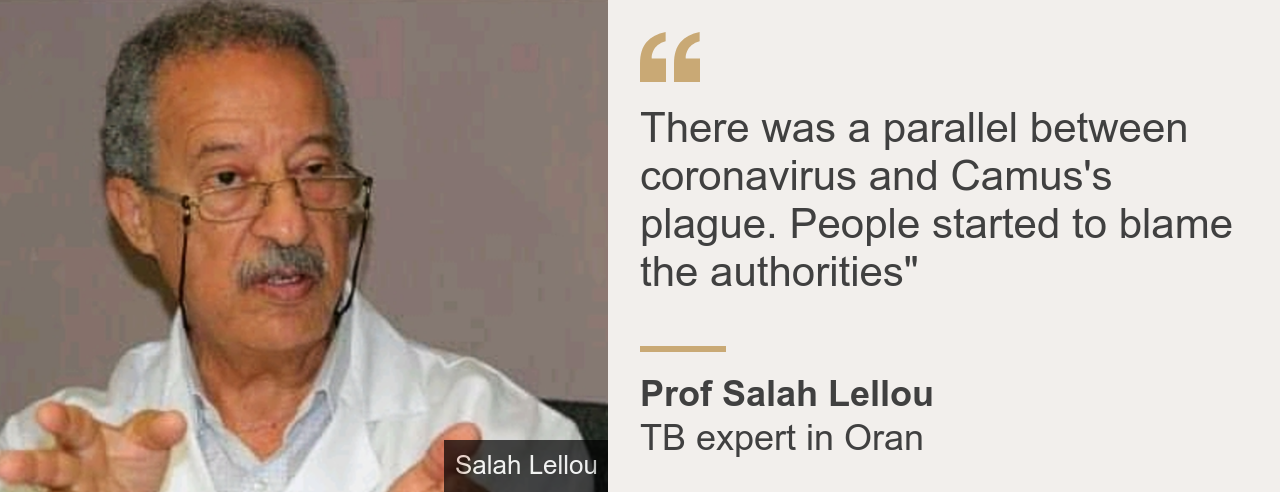

Sitting in his office in the Mohamed-Boudiaf Hospital, where many of Oran's coronavirus cases are treated, Professor Salah Lellou says he is exhausted.

An expert on tuberculosis in Algeria's second city, he's been working flat out for months, rarely leaving the hospital before midnight.

"The sick arrived in a very serious condition. Everyone was panicking - patients and the staff. We had a terrible time of it.

"We're not sure if we've arrived at the peak, or if there's a second wave because right now we have another spike in cases."

Haunted by the novel

The third worst affected country in Africa after Egypt and South Africa, Algeria has officially reported 43,016 cases of coronavirus, including 1,475 deaths.

Oran, a port city on the Mediterranean, was the setting for The Plague, which in the novel was in total lockdown

It imposed a strict lockdown after the first infection was recorded at the end of February and in much of the country night-time curfews remain in force.

With his salt and pepper moustache and receding hair, Prof Lellou is older than Camus' hero, Dr Bernard Rieux, but he seems equally devoted to his patients.

Unlike many in Oran today, he is familiar with the novel set in his hometown and almost seems haunted by it.

"We weren't able to avoid thinking about the plague Albert Camus described during this pandemic… Most patients were very scared, there were a lot of rumours going around. Everyone was caught off-guard."

Medics have been under pressure during the pandemic

In Bouira, east of the capital, Algiers, a hospital director was cornered by angry relatives of a patient who had just died of Covid. He jumped out of the second-floor window of his office to escape, suffering multiple fractures.

"There was a parallel between coronavirus and Camus' plague. People started to blame the authorities," says Prof Lellou.

In Camus' novel, the Cathedral of Sacré-Cœur in downtown Oran - now a public library - was the setting for a fiery sermon delivered by the Catholic priest, Father Paneloux, who tells the congregation they have "deserved" the calamity which has befallen them.

Because of the coronavirus pandemic, Algeria's mosques have been closed and religious leaders like Sheikh Abdelkader Hamouya have been delivering health messages and sermons online.

He has a reputation as a progressive but when he reflects on the meaning of the pandemic, there are echoes of Camus' 1940s Jesuit priest.

"As far as I'm concerned, it's a message from Allah to believers, and to all people, to come back to him. To wake up!" he says.

Virus halts protests

Many Algerians tell me that the real danger they face is less the coronavirus itself and more the way the authorities are exploiting it for other purposes.

The protesters want reforms in a country where a third of young people are unemployed

Before the pandemic brought the world to a standstill, Algeria was swept up in a wave of peaceful protests - known as the Hirak, Arabic for "Movement" - which eventually forced President Abdelaziz Bouteflika to step down in April 2019 after 20 years in power.

Despite the celebrations that followed, the candidates to replace the aged president all belonged to the old guard. A former prime minister became head of state in December after widely boycotted elections.

Abdelmadjid Tebboune promised to extend a hand to the Hirak movement to build a "new Algeria". He talked of reforms and the need to "separate money from politics".

But with no sign of desperately needed jobs, protests became increasingly tense, with scores of activists arrested.

The authorities say Algeria is threatened by a rerun of the bloody violence of the 1990s - known as "the black decade".

Young volunteers have been distributing donated food aid to needy families during the lockdown

Just as the stand-off seemed to be reaching a climax, coronavirus emptied the streets. Activists like Afiff Aderrahmane agreed to temporarily halt the protests.

The web designer threw himself into charity work, setting up a website to put donors in touch with organisations which distribute food and other aid to needy families and the homeless during the lockdown.

"The Hirak during the quarantine transformed itself into one enormous act of solidarity," he says.

Solidarity during a crisis is a major theme in The Plague.

Mr Aderrahmane could be seen as a modern-day version of Camus' character, Jean Tarrou, who organises sanitary teams of volunteers to accompany doctors on house visits, transport the sick and support those in quarantine.

"In fact many Algerians have something in common with him... the urge to help others in difficult times," says Mr Aderrahmane.

Fascism and repression

The sanitary teams organised by Tarrou may reflect Camus' own experience of fighting in the French resistance.

Walid Kechida, portrayed here by cartoonist Nime, is behind bars for irreverent images shared on Facebook

Written just after World War Two, the novel has often been interpreted as an allegory for the Nazi occupation of France with the rats that bring the disease representing the "brown plague" of fascism.

But it can be interpreted in myriad ways and may also contain lessons for the excesses of an authoritarian state.

Walid Kechida, the young creator of Facebook page Hirak Memes, external, was charged in April with offending the president and religious authorities with his irreverent images.

Although the authorities released some political prisoners to mark Independence Day on 5 July, many high-profile detainees like Kechida remain behind bars.

Earlier this month, prominent journalist Khaled Drareni was sentenced to three years for "inciting an unarmed gathering" and "endangering national unity".

The government also passed a controversial law against "fake news" and blocked three websites that had been covering the pandemic and protests.

From 4,000 miles away, a radio station has been trying to fill the information gap.

Radio Corona International was set up by Abdallah Benadouda, an Algerian journalist now based in Providence, Rhode Island, in the US.

In 2014, he got on the wrong side of Said Bouteflika, the then-president's brother, was sacked, blacklisted and after getting death threats, he and his wife fled.

The radio station airs each Tuesday and Friday to pay homage to the days of the street protests - and Benadouda says it helps to keep the flame of the Hirak burning.

You may also be interested in:

There were jubilant scenes after President Bouteflika resigned

"I'm trying to do my best to be part of the revolution. So my body is in Providence but my mind and my heart are in Algeria."

In The Plague, there is a French journalist - Raymond Rambert - who's been sent to report on housing conditions in Oran and finds himself trapped as the city goes into lockdown. He is desperate to return home.

I think of Benadouda as the mirror opposite of Camus' character. He is a journalist stuck on the outside, yearning to get back in. And his anguish increases with the mounting repression in Algeria as he worries about the safety of his contributors there, where frustration is increasing.

'Inoculated against violence'

But like the vast majority of Algerians, Benadouda fears chaos. During the 1990s when the military fought an Islamist insurgency, 200,000 people died and 15,000 were forcibly disappeared.

Abdelkader Djeriou, the star of a gritty TV drama set in Oran, agrees. The actor often addressed huge crowds during the Hirak and was briefly imprisoned last December.

"Our experience of what we call 'the black decade' has inoculated us, it gave us some maturity to not be confrontational, and to avoid violence.

"This pandemic has really caused the mask to slip. We've seen that it's civil society which helps the poor and those in need."

Camus understood that when disaster strikes, people show their true colours.

The current crackdown on anti-government protests is a far cry from the freedom Algerians enjoyed at the start of the Hirak.

Algerians who know the novel might have recognised Camus' warning against complacency at the very end of the book when he says that the plague bacillus - however the reader interprets it - never dies or disappears for good.

You can listen to Lucy Ash's BBC World Service Assignment programme about Algeria's Plague Revisited here.

VACCINE: How close are we to finding one?

GLOBAL SPREAD: Tracking the pandemic

HOW A VIRUS SPREADS: An explanation

- Published9 September 2024