Tunisians question whether life is better after Arab Spring

- Published

A third of young Tunisians are unemployed

"Be honest, can you really say things are better today?" It is a question I have often been asked, by Tunisia's poor and privileged alike, as well as those in-between.

One could ask, what is the measure of "better"?

The 10th anniversary of the events in Tunisia that kickstarted what we call the Arab Spring, has coincided with a four-day national lockdown to control alarming rates of Covid-19 infections. The following night saw violent confrontations between groups of youths and the police in over a dozen working-class neighbourhoods across the country.

Security forces used tear gas and water cannon on the protesters

It wasn't initially clear what triggered them, and civilians and officials were deeply split over how best to describe them - were they protests or riots? And what were they really all about?

Some said they were caused by impoverished, hungry, and angry young people. More than 600 of them, mostly teenagers, were later arrested. The next day dozens of protestors came out in the centre of the capital, Tunis, against the arrests, reviving revolutionary chants calling for "the fall of the regime".

But few Tunisians are clear on what that would entail today. The last parliamentary and presidential election was less than two years go.

Some demonstrators are also demanding that the names of people who died in the 2011 uprising be listed as martyrs

There is no question that people here are hurting - financially and socially - or that vital public services are declining. There have been annual bouts of civil unrest in recent years, usually demanding jobs and better pay.

For 10 years, across the region, I have witnessed a lot of confusion and struggle. A sense of gain one day, matched by a sense of loss the next, and an inch of hope one year that is later engulfed by hopelessness, to varying degrees.

Tunisia has been trapped in a soft cycle of that turmoil.

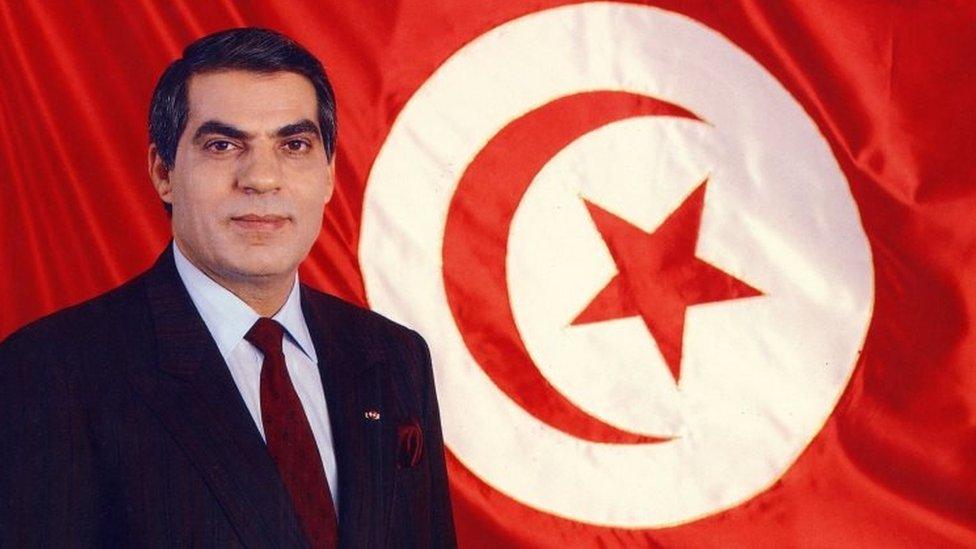

Then-president Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali was forced from power by the wave of protests 10 years ago

What Tunisia achieved in beginning its political and democratic transformation has not been matched by deeper economic and social development. The reality is that when former President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali was toppled from power, the economy tanked, and has not recovered since.

Who is responsible for that?

People blame an entrenched system that allows corruption, or the political rivalry in parliament that crippled numerous governments. Tunisia has had 12 in 10 years - consensus politics was abandoned a long time ago.

The IMF loans with their conditions are also a source of economic pressure.

Wrangles over wages have led to strikes and protests in vital sectors, including health, transport and natural resources.

You may also be interested in:

So, what do people want?

A Tunisian businessman who imports food products recently told me: "We need something in-between... a strong leader who supports freedoms. This parliament, and all these political parties who work against each other are paralysing the country."

In Ettadhamen, one of the capital's most densely populated and underprivileged suburbs, where young people took to the streets this month and clashed with the police, there is a similar view.

Security forces fired tear gas at protesters in the Tunis suburb of Ettadhamen on Monday

Wael is a 27-year-old civil society activist. "Some people here are now asking for the parliamentary system to be removed," he tells me.

"The president has no power, he's like a symbol of the state only."

I listened with intrigue - here is a young man from a neighbourhood that is reputed to have been the pulse of the 2011 revolution that overthrew an all-powerful president, now asking for a head of state with yet more power.

"It's true we have freedoms now," he admits, "but we discovered that our dreams will not materialise".

When I ask him about the teenagers who were arrested recently, Wael quickly points to the high number of school drop-outs in his area. "Maybe this system we have works elsewhere, but it doesn't work here… all the political parties failed us."

Tunisia's prime minister has acknowledged general "legitimate anger" brought on by the economic crisis

I have a video call with Chokri al-Laabidi, an Arabic-language teacher from the same area, who once stood and led his street in demonstrations against the former regime in 2011. I find he's not happy about the recent unrest, describing some of the protesters as "violent", with no tangible demands.

Reflecting on the last decade, he thinks that there is a tendency to focus on what's still wrong instead of what's better - "the change people want," he explains, "is a matter of time".

So, I ask him, what is better now?

"The municipalities are elected and have more power - there is freedom of speech today, and there is a mechanism to hold anyone and everyone to account - this did not exist before," he tells me.

In his spare time he runs a local youth group, and is under no illusion that things are working perfectly.

"But I have faith in freedom," he tells me. "As long as it is there, it guarantees change… and a way to make fewer mistakes".

Related topics

- Published18 October 2019

- Published3 April 2020

- Published19 September 2019

- Published9 October 2024