Ethiopia's Tigray crisis: What a blind man's death reveals

- Published

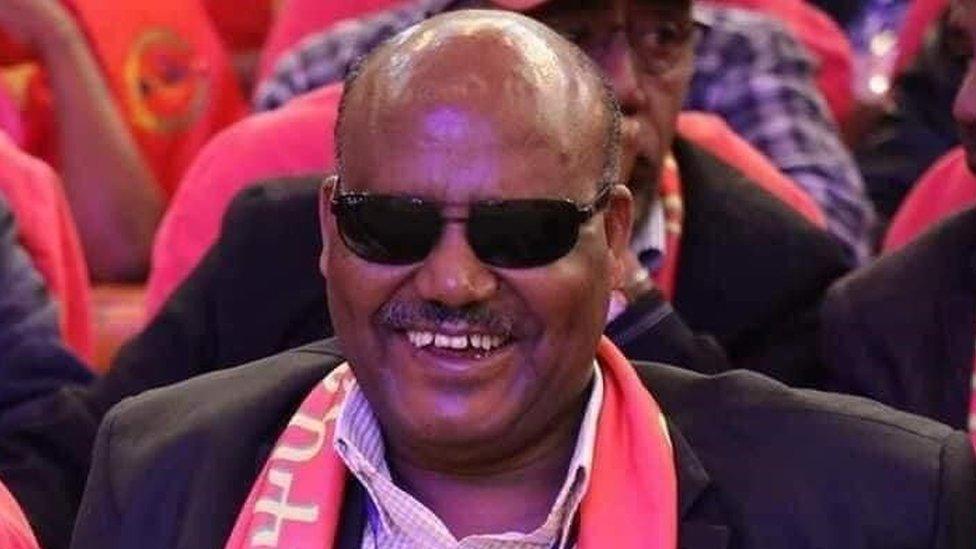

The injury-plagued life, and now death, of Asmelash Woldeselassie highlights the brutality and cyclical nature of conflicts in Ethiopia's mountainous Tigray region.

Having joined the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) around the time of its formation in 1975, Asmelash lost his eyesight when he was bombed in his hideout in the Imba Alaje mountain during the war that ended with the guerrilla movement marching into Ethiopia's capital, Addis Ababa, to seize power from the notorious Mengistu Haile Mariam regime in 1991.

Then in 1998, when the TPLF-led government found itself at the centre of a border war with Eritrea, Asmelash lost his left arm in an airstrike on the regional capital, Mekelle.

In the latest conflict that has seen the TPLF return to being a guerrilla movement, Asmelash - who was a member of its executive - was killed along with two other TPLF veterans - former foreign minister Seyoum Mesfin and former minister of federal affairs Abay Tsehaye.

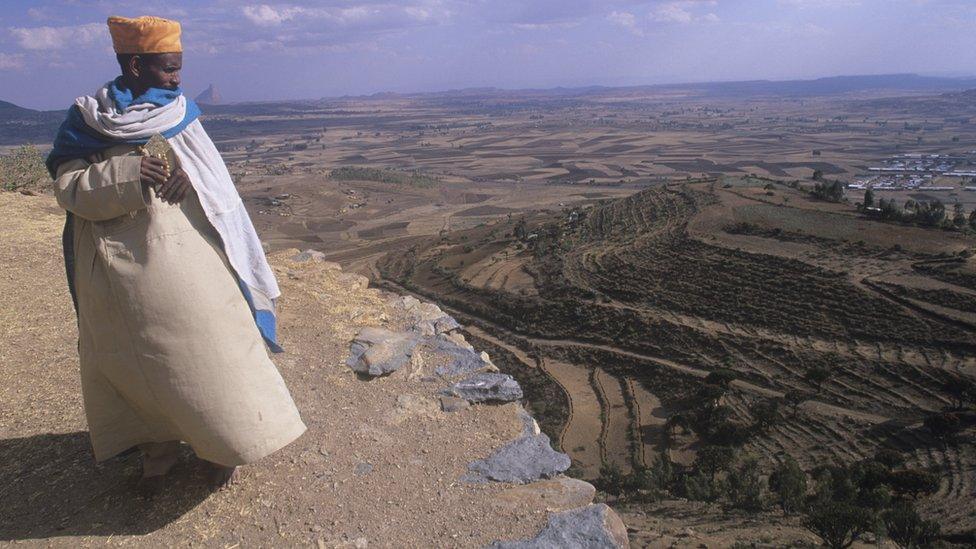

Tigray is a sparsely populated mountainous region

Ethiopia's 44-year-old Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed - who ordered the military operation that ultimately led to their deaths - was a junior member of the TPLF-led coalition government until his rise to power in 2018.

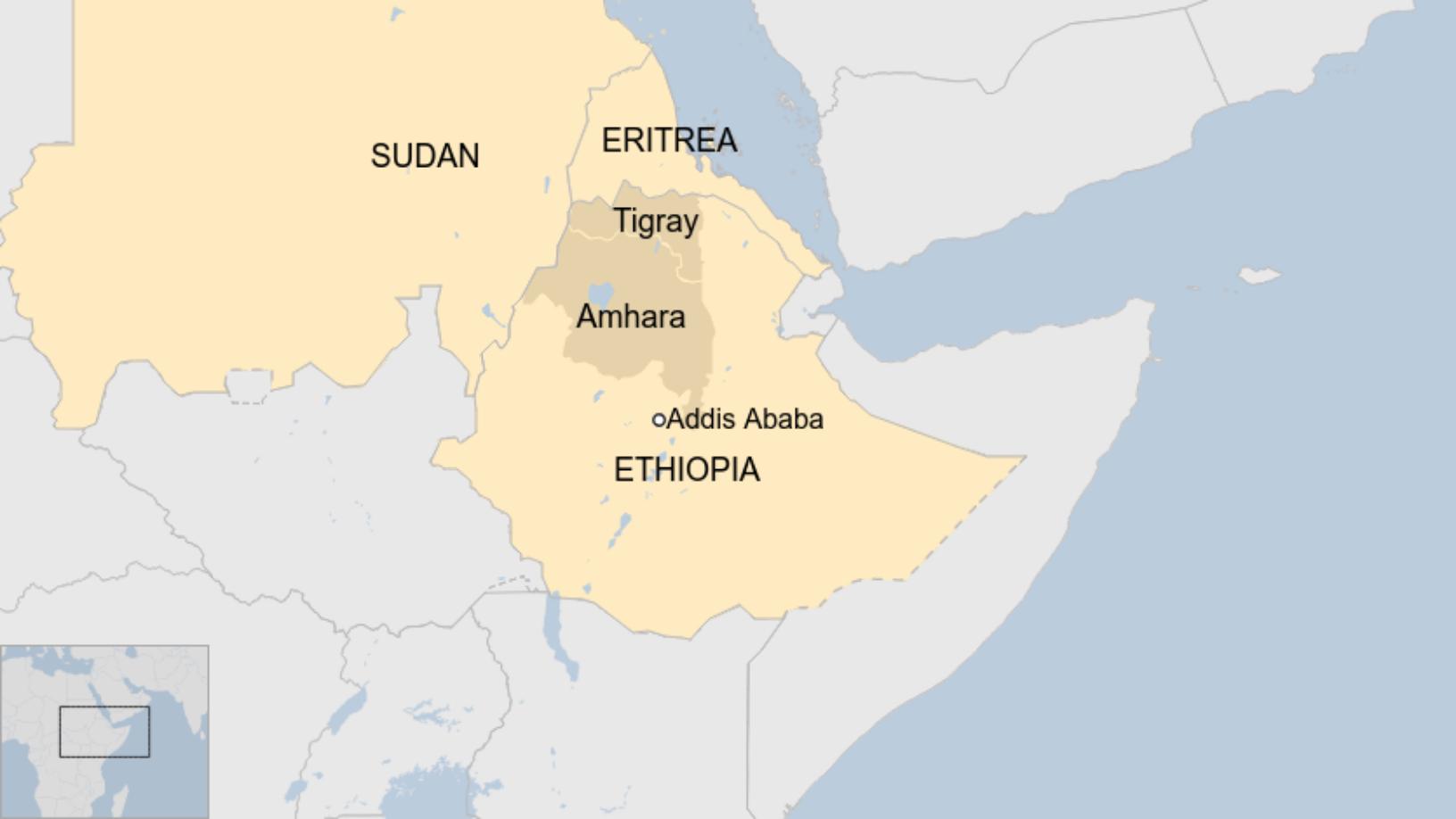

Now, he and the TPLF are enemies fighting for control of Tigray, a strategically important region which borders Sudan and Eritrea, the gateway to the shipping routes of the Red Sea.

Eritrea's President Isaias Afwerki has reportedly sent troops to Tigray to bolster the Ethiopian military's operation and, some say, to avenge his humiliation at the hands of the TPLF during the 1998-2000 border war that left up to 100,000 people dead.

Both governments deny Eritrean troops are in Tigray, despite many Tigrayans, Eritreans and the US government saying they are there.

Mr Abiy declared victory over the TPLF following the capture of the regional capital, Mekelle, on 28 November, but vowed that efforts to apprehend the TPLF "clique" - which was estimated to have 250,000 fighters under its command - would continue.

Handcuffed and dishevelled

How Asmelah, Seyoum and Abay - all aged over 60 - died is unclear: some allege they were shot dead in cold blood, but the official Ethiopian version is that they were killed in a cave area after they refused to surrender.

Their deaths came on top of the capture of several other TPLF stalwarts - including Sebhat Nega, who was paraded in front of the cameras in handcuffs and looking dishevelled, in a scene reminiscent of the capture of Iraq's former ruler Saddam Hussein in 2003.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Faisal Roble from the US-based Institute for Horn of Africa Studies and Affairs said that supporters of Mr Abiy are celebrating the fate of the men who belonged to an organisation that had ruled Ethiopia with an iron hand until mass protests forced it to relinquish power to Mr Abiy nearly three years ago.

"They are saying: 'We got the TPLF. We are destroying it. They will never be able to oppress us again.'

"But Tigrayans - including those who never liked the TPLF - are saying: 'You killed Asmelash, a blind man, Seyoum, who had back surgery and struggled to walk, Abay, who had heart surgery, and you humiliated Sebath, who can't walk up two stairs. These are our heroes.'"

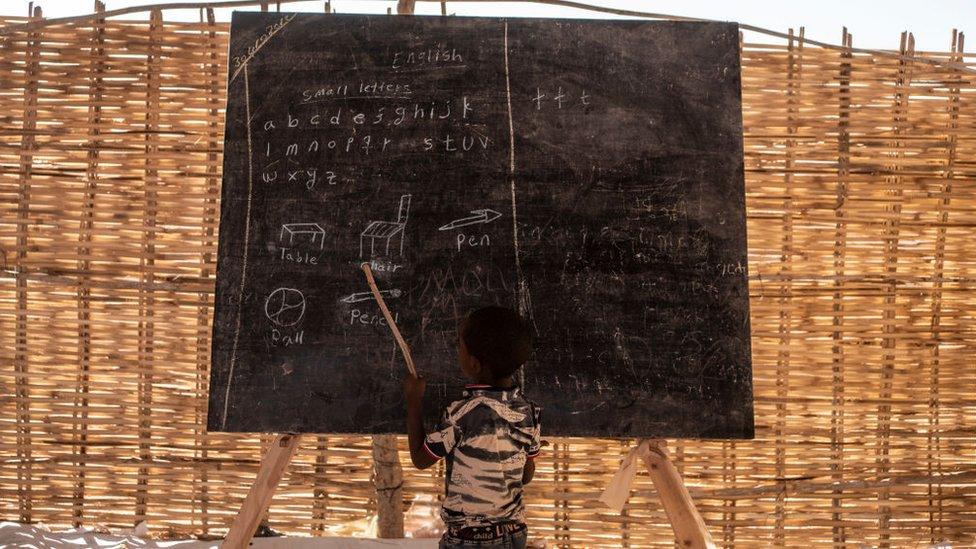

About 60,000 people from Tigray are in refugee camps in Sudan

Exiled Eritrean human rights campaigner Paulos Tesfagiorgis said there was no doubt that almost three months into the conflict, the TPLF has suffered major setbacks after being hit by drone strikes and the massive deployment of Ethiopian and Eritrean troops, as well as forces from Ethiopia's Amhara region, which under the country's federal system has its own land dispute with Tigray.

"The TPLF has lost a lot of ground, a lot of leaders, a lot of fighters, and a lot of heavy weaponry. It now has only medium and light weapons. I don't think it expected Eritrea to get involved to the extent it has.

"Isaias has pursued his old strategy of overwhelming the enemy with troops, tanks, armament, and bombings," Mr Paulos said, adding: "But the TPLF is not finished. It fought intense battles. Now, it has returned to familiar ground, the rural areas of Tigray, its mountains and hills, to wage a guerrilla war."

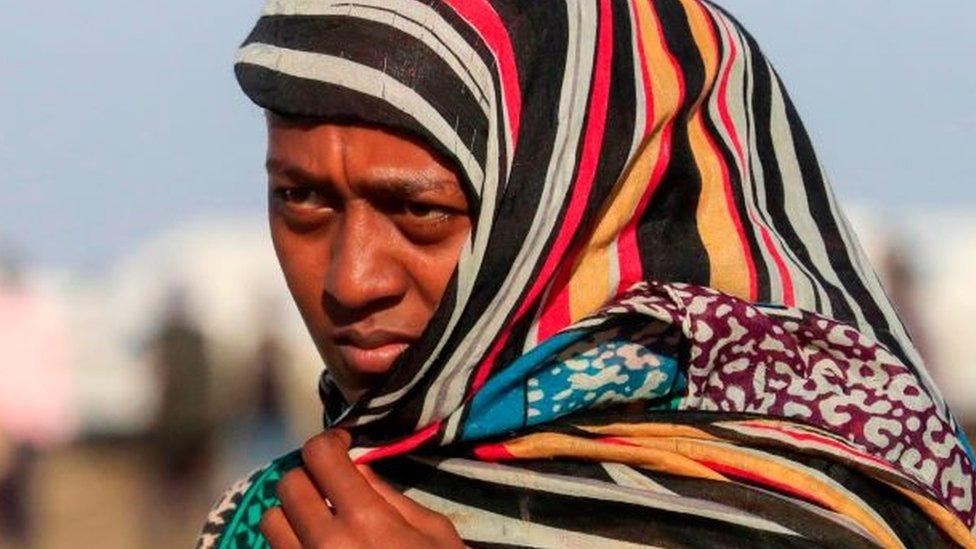

Many Tigrayans fled on foot and by boat to Sudan

Menychle Meseret, an academic at Ethiopia's University of Gondar, said the TPLF's move to guerrilla warfare, after waging a "full-scale" conflict against the Ethiopian military, posed its own dangers.

"With insurgent groups, even one suicide bomber can cause a lot of deaths. In the case of the TPLF, it has some remaining fighters. There are reports of fighting in some mountainous areas, and of the TPLF having already carried out ambushes on roads - even on an aid convoy."

Warnings of famine

Mr Paulos said he believed that the government was using starvation as a weapon of war.

"Government soldiers burnt the crops of Tigrayans; the offensive happened during the harvest season, and slaughtered their livestock. This was happening while the government imposed a total blockade on Tigray. No food was getting in. Even now, the flow of aid is heavily restricted.

"People are already dying of hunger. There are warnings of a famine. This is a war waged without compassion. It reminds me of Mengistu's quote: 'To kill the fish, drain the pond'." In order to weaken the TPLF, Abiy's government has to subdue the civilians, including subjecting them to hunger," Mr Paulos said.

Many refugees are worried about the relatives they have left behind

Aid agencies have reported that the conflict - which came amid the coronavirus pandemic and a locust infestation of crops - had caused a "dire" situation:

More than two million people are in need of aid

Mass displacements have raised fears of a "massive" transmission of Covid-19

Only five out of 40 hospitals are accessible

Some 300 motorized water sources are dysfunctional

Local markets are near collapsing

An official in the newly appointed administration in Tigray was quoted by local media as saying that the crisis in the region was "unprecedented in its history", external. He put the number who required emergency food aid at 4.5 million (up to 75% of the population), the number of displaced at 2.5 million, and said his office had received reports of 13 people - including three children - having died of hunger.

The government has denied using starvation as a weapon of war, external, and Mr Menychle said such accusations were "completely wrong".

"The government has enough food stocks but it can't deliver them in rural areas because the TPLF is killing drivers. The TPLF wants to orchestrate starvation as a weapon to manipulate global opinion and get sympathy for its cause.

"The TPLF gave guns to farmers, and forced some of them to fight. That is why crops ended up being destroyed. The TPLF also controlled the government administration of all towns. It destroyed offices - even hospitals - before it abandoned towns," Mr Menychle said.

The state-linked Human Rights Commission said that residents of the agricultural hub of Humera in western Tigray had reported widespread looting of houses and businesses by an ethnic Amhara youth group, militias, special forces, as well as some Ethiopian and Eritrean soldiers.

"Looters have also emptied food and grain storages," it said, adding that a resident had complained that even people sent by the newly appointed administration to help them "take part in theft", external.

More on the Tigray crisis:

The International Crisis Group's Ethiopia analyst William Davison said the federal government was delivering some aid into areas where its troops, or security forces from Amhara, were firmly in control.

But this was not happening in areas where Tigrayan forces were still a major threat, as the government would not want them to get hold of aid supplies or to find ways of smuggling in fuel or arms.

"Large swathes of rural Tigray have not been receiving any aid because there is insufficient federal control or too much insecurity.

"Aid is going into Mekelle, the regional capital, and some parts of the south or west, as federal or Amhara forces are in control in these places," he said.

'Eritrean troops in sacred city'

Mr Davison added that to get aid into areas under the control of Eritrean troops was also difficult logistically and politically, as there was as yet no acknowledgement from either the Ethiopian or Eritrean leadership that the latter's forces have been part of the Tigray conflict.

Is Aksum the home of the Ark of the Covenant?

Local people told the BBC that Eritrean forces were in key cites and towns, including Aksum, the most sacred site for Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, and Wukro, only about 45km (28 miles) from Mekelle.

They had withdrawn from Shire, the birthplace of Tigray's ousted President Debretsion Gebremichael, after helping Ethiopian forces take control of it, but they still had a strong presence in surrounding villages, residents said.

Sudan's key role

Martin Plaut - a senior research fellow at London University's Institute of Commonwealth Studies - said that control of territory was not an indicator of who was winning.

"The TPLF does not believe in holding cities and towns. It fights from the hills and mountains. It lets the enemy settle down.

"It then carries out hit-and-run attacks. It wears out the enemy over months and years. This is what it did in the previous guerrilla war. Whether it can wage an effective guerrilla war again depends on whether it can secure supply routes for ammunition, fuel and food," Mr Plaut said.

The last time around, the TPLF got its supplies through Sudan. Whether Sudan agrees to do so again - amidst a border dispute with Ethiopia that has led to clashes between their forces - was the big question, Mr Plaut said.

"It is likely to determine whether this is a long or a short war."

Related topics

- Published25 January 2021

- Published6 December 2020

- Published20 December 2020

- Published17 December 2020

- Published10 December 2020

- Published3 January 2021