Nourin Mohamed Siddig: The African art of reciting the Koran

- Published

Social media has enabled a revival in unique African styles of Koranic recitation, which were once dominated by Middle Eastern traditions and as Isma'il Kushkush reports a voice from Sudan has come to exemplify what the continent has to offer.

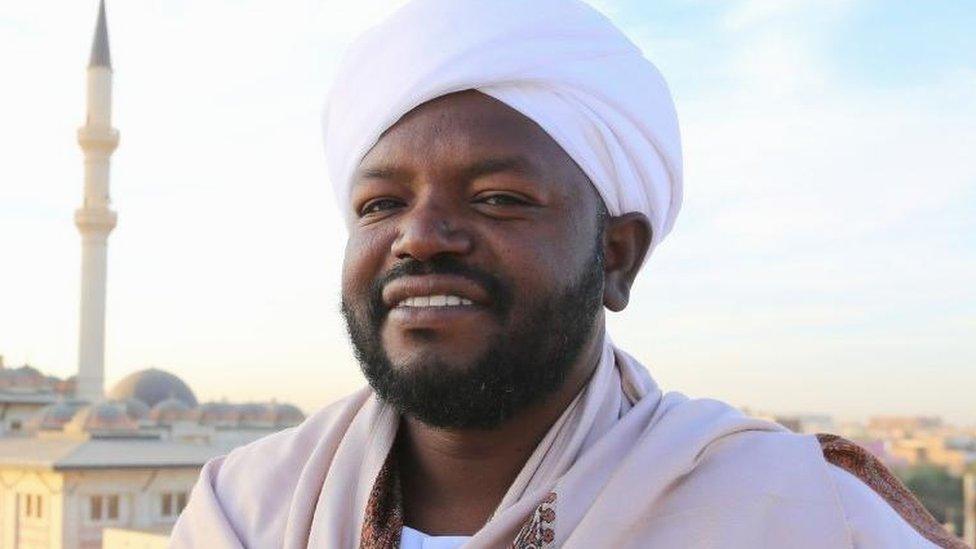

When Nourin Mohamed Siddig recited the Koran, people around the world described his tone as sad, soulful and bluesy.

His unique sound made him one of the Muslim world's most popular reciters.

As a consequence, his death at the age of 38 in a car accident in Sudan in November was mourned from Pakistan to the United States.

"The world has lost one of the most beautiful [voices] of our time," tweeted Imam Omar Suleiman of Texas.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Hind Makki, a Sudanese-American interfaith educator, said it had a hard-to-describe quality.

"There is an African authenticity that people point to even if they are not able to articulate exactly what it is and they like it," she said.

The comparison made with Blues music is not an accident.

According to historian Sylviane Diouf the chants, prayers and recitation of enslaved West African Muslims - which can sound similar to that of Muslims across the Sahel region to Sudan and Somalia - may have contributed to the creation of "the distinctive African American music of the South that evolved into the holler and finally the Blues".

According to tradition, the Koran, Islam's holy book, is typically recited in a singing manner, encouraged by the Prophet Muhammad, who said that people should "beautify the Koran with your voices".

Different places, different approaches

It is especially appreciated when large numbers come together for religious occasions such as evening prayers in the month of Ramadan, taraweeh.

There are even several international recitation competitions.

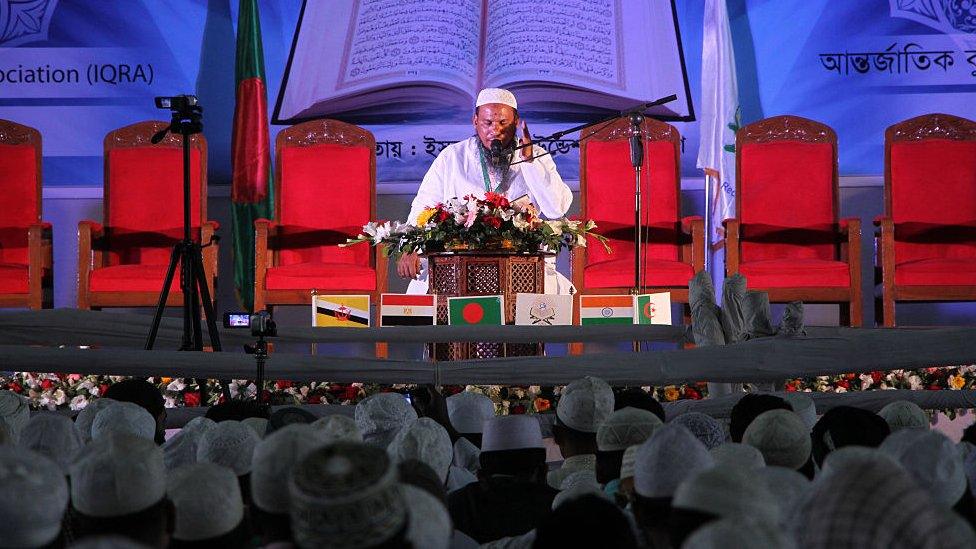

Overlooked at times, however, is the fact that there are many approaches to reciting the Koran.

Different styles can be heard at recitation conferences like this one in Bangladesh in 2017

These may differ in tone and articulation according to geography, culture and historical experiences in the vast Muslim world beyond its heartland in the Middle East.

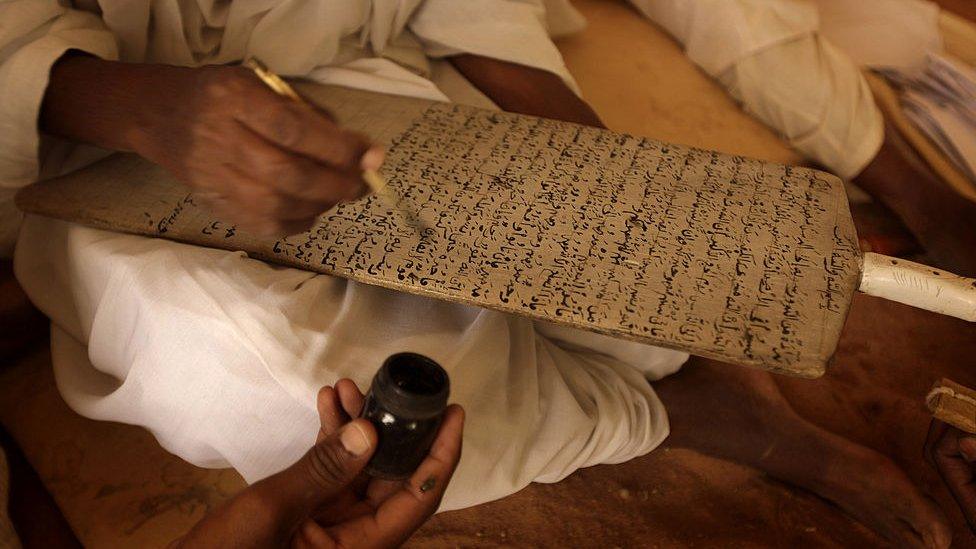

Siddig's recitations and untimely death brought greater attention to a traditional African style. He picked up the tone studying in a traditional Koranic school in his village of al-Farajab, west of the capital, Khartoum, in the mid-1990s.

When he later moved to Khartoum, he led prayers in a number of the city's main mosques and caught people's attention. His fame spread once videos of him were uploaded to YouTube.

This is the tone of the environment I grew up in, the desert; it sounds like [Sudanese folk-music genre] dobeit"

While sounds described as reflective of a seven-note heptatonic scale are popular in the Middle East, Siddig's recitation mirrored the five-note or pentatonic scale that is common in Muslim-majority regions of the Sahel and the Horn of Africa.

"This is the tone of the environment I grew up in, the desert; it sounds like [Sudanese folk-music genre] dobeit", said Al-Zain Muhammad Ahmad, another popular Sudanese reciter.

"The reciters in the Levant recite according to the melodies they know, as do the ones in Egypt, the Hijaz, North Africa and elsewhere."

This view is backed up by musicologists such as Michael Frishkopf, music professor at the University of Alberta in Canada.

While he cautions about lumping sub-Saharan Africa into one sonic tradition, he does confirm that the pentatonic scale is widely present in the region.

"Broadly speaking you won't find pentatonic or hexatonic [six-note] recitation in Egypt, whereas you do find it in Niger and Sudan, Ghana and The Gambia."

Imam Omar Jabbie of Olympia, Washington state, is a graduate of the prestigious Islamic University in Medina, Saudi Arabia. He was born in Sierra Leone and first learned to recite the Koran with teachers in Senegal and The Gambia.

"That's where I learned many Koranic tones," he explained.

In recent decades, Middle Eastern styles of reciting the Koran began to dominate in many regions in Africa and worldwide, especially in urban areas. Listeners of the Koran had access to recordings through vinyl records, shortwave radio broadcasts, audio cassette tapes and CDs, produced and distributed or sold by organisations largely from Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Returning students from Egypt's Al-Azhar University and the Islamic University in Medina, and the impact of Gulf-funded charities, also helped spread and popularise these Middle Eastern styles among many reciters globally, including those from sub-Saharan Africa, with some even excelling in this approach.

Some saw, and propagated it, as more authentic, which at times was at the expense of local traditions.

Siddig would have studied the Koran on boards like this one where the verses are handwritten

But the internet and social media in particular has brought renewed attention, especially from a younger generation, to traditional voices.

"The democratising forces of the social media and modern technology has mitigating effects on these historical forces," explained Professor Mbaye Lo, who researches the sociology of Islam.

Elebead Elshaifa of Naqa Studio, a Khartoum-based media production company established in 2016 elaborated.

"Social media doesn't need the same requirements of a satellite television station," he said, pointing to lower costs and fewer legal restrictions.

Global appeal

Ahmad Abdelgader, an amateur videographer has been recording Imam Jabbi's recitations for his YouTube channel since 2017.

"The most popular video recording is the African style supplication [du'a] with over two million views, external," he said. "Most of the people watching were from France, where many West African Muslims live, followed by the United States."

These online recordings have also brought attention to different schools of verbalising the Koran, qira'at.

The Koran, for Muslims, is believed to have been transmitted according to seven schools of verbalisation that vary slightly in how some words are read.

The most well-known of these schools today is Hafs, mandated by the Ottoman Turks in the lands they conquered and later widely taught in institutions of learning and distributed through printed copies of the Koran made in Cairo and Mecca.

But in some parts of the Muslim world, especially in rural areas of the African continent, other schools of verbalisation continued to be used such as al-Duri in Sudan, which Siddig often followed in his recitations.

His recitation style was a reminder of both the universal and diverse traditions among Muslims and for many followers and observers there is a clear lesson here.

While the content and letter of the Koran is largely agreed upon, different recitation styles provide a universal message expressed through a "beautiful combination of local sound and global semantics," explains Prof Frishkopf.

"This is the key point."