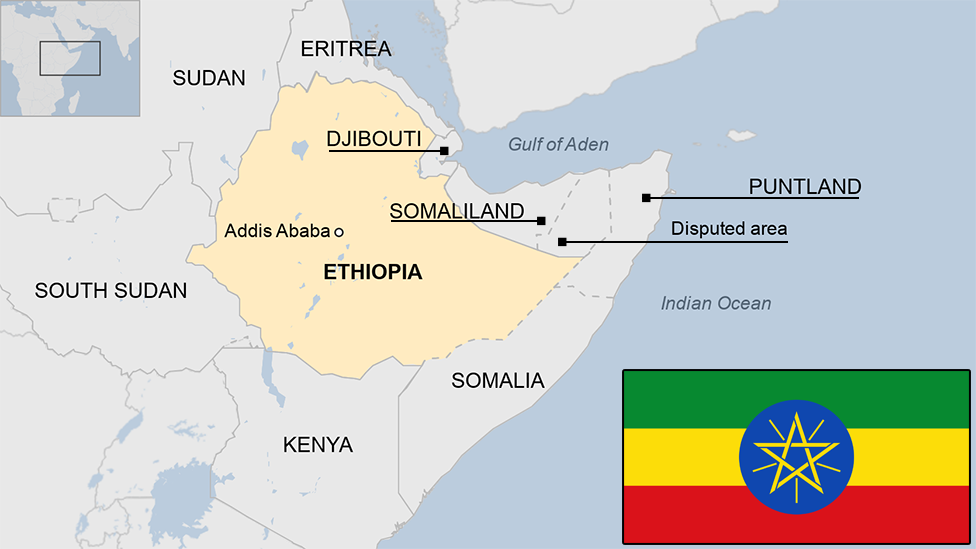

Ethiopia's Tigray crisis: How a massacre in the sacred city of Aksum unfolded

- Published

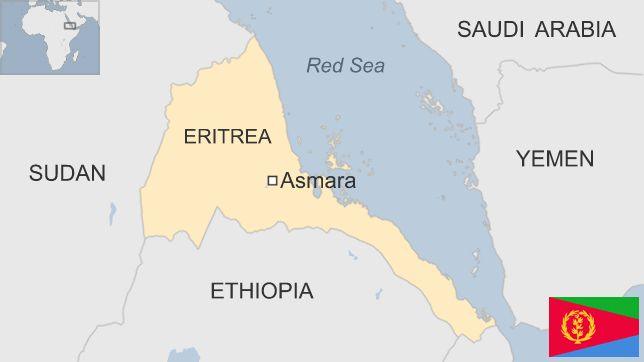

Aksum is said to be the birthplace of the biblical Queen of Sheba

Eritrean troops fighting in Ethiopia's northern region of Tigray killed hundreds of people in Aksum mainly over two days in November, witnesses say.

The mass killings on 28 and 29 November may amount to a crime against humanity, Amnesty International says in a report.

An eyewitness told the BBC how bodies remained unburied on the streets for days, with many being eaten by hyenas.

Eritrea's Information Minister Yemane G Meskel has dismissed the accusations as "preposterous" and "fabricated".

In a tweet, external, he suggested that the eyewitnesses quoted were militiamen allied to Tigray's former ruling party, the TPLF, whose dispute with Ethiopia's federal government led to the conflict in the region.

Ethiopia's government has promised a joint investigation with international actors. While it cast questions on Amnesty's methodology, it admitted "serious issues that should be of great concern" were raised.

Both Ethiopia and Eritrea deny that Eritrean forces have been involved in the Tigray conflict.

The conflict erupted on 4 November 2020 when Ethiopia's government launched an offensive to oust the TPLF after its fighters captured federal military bases in Tigray.

Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, told parliament on 30 November that "not a single civilian was killed" during the operation.

But witnesses have recounted how on that day they began burying some of the bodies of unarmed civilians killed by Eritrean soldiers - many of them boys and men shot on the streets or during house-to-house raids.

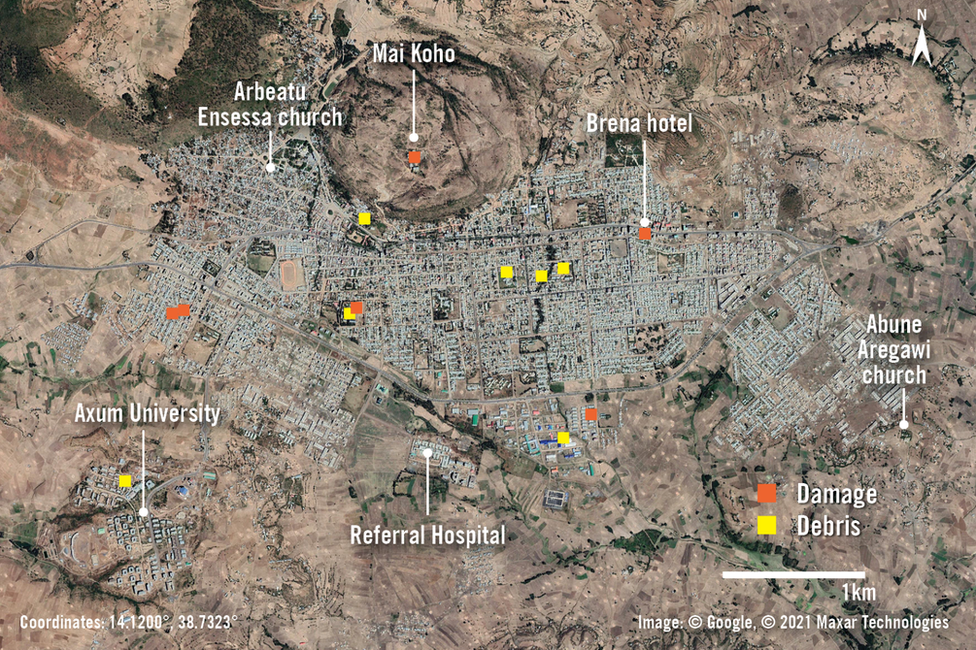

Amnesty's report has high-resolution satellite imagery from 13 December showing disturbed earth consistent with recent graves at two churches in Aksum, an ancient city considered sacred by Ethiopia's Orthodox Christians.

A communications blackout and restricted access to Tigray has meant reports of what has gone on in the conflict have been slow to emerge.

In Aksum, electricity and phone networks reportedly stopped working on the first day of the conflict.

How was Aksum captured?

Shelling by Ethiopian and Eritrean forces to the west of Aksum began on Thursday 19 November, according to people in the city.

"This attack continued for five hours, and was non-stop. People who were at churches, cafes, hotels and their residence died. There was no retaliation from any armed force in the city - it literally targeted civilians," a civil servant in Aksum told the BBC.

Amnesty has gathered similar and multiple testimonies describing the continuous shelling that evening of civilians.

Once in control of the city, soldiers, generally identified as Eritrean, searched for TPLF soldiers and militias or "anyone with a gun", Amnesty said.

"There were a lot of... house-to-house killings," one woman told the rights group.

There is compelling evidence that Ethiopian and Eritrean troops carried out "multiple war crimes in their offensive to take control of Aksum", Amnesty's Deprose Muchena says.

What sparked the killings?

For the next week, the testimonies say Ethiopia troops were mainly in Aksum - the Eritreans had pushed on east to the town of Adwa.

A witness told the BBC how the Ethiopian military looted banks in the city in that time.

The conflict has left Tigray's population in dire need of humanitarian aid

The Eritrean forces reportedly returned a week later. The fighting on Sunday 28 November was triggered by an assault of poorly armed pro-TPLF fighters, according to Amnesty's report.

Between 50 and 80 men from Aksum targeted an Eritrean position on a hill overlooking the city in the morning.

A 26-year-old man who participated in the attack told Amnesty: "We wanted to protect our city so we attempted to defend it especially from Eritrean soldiers... They knew how to shoot and they had radios, communications... I didn't have a gun, just a stick."

What did Eritrean troops do?

It is unclear how long the fighting lasted, but that afternoon Eritrean trucks and tanks drove into Aksum, Amnesty reports.

Witnesses say Eritrean soldiers went on a rampage, shooting at unarmed civilian men and boys who were out on the streets - continuing until the evening.

More on the Tigray conflict:

A man in his 20s told Amnesty about the killings on the city's main street: "I was on the second floor of a building and I watched, through the window, the Eritreans killing the youth on the street."

The soldiers, identified as Eritrean not just because of their uniform and vehicle number plates but because of the languages they spoke (Arabic and an Eritrean dialect of Tigrinya), started house-to-house searches.

"I would say it was in retaliation," a young man told the BBC. "They killed every man they found. If you opened your door and they found a man they killed him, if you didn't open, they shoot your gate by force."

He was hiding in a nightclub and witnessed a man who was found and killed by Eritrean soldiers begging for his life: "He was telling them: 'I am a civilian, I am a banker.'"

Witnesses says roads in Aksum were littered with bodies

Another man told Amnesty that he saw six men killed, execution-style, outside his house near the Abnet Hotel the following day on 29 November.

"They lined them up and shot them in the back from behind. Two of them I knew. They're from my neighbourhood… They asked: 'Where is your gun' and they answered: 'We have no guns, we are civilians.'"

How many people were killed?

Witnesses say at first the Eritrean soldiers would not let anyone approach the bodies on the streets - and would shoot anyone who did so.

One woman, whose nephews aged 29 and 14 had been killed, said the roads "were full of dead bodies".

Many of the burials are reported to have taken place at Aksum's Arba'etu Ensessa church

Amnesty says after the intervention of elders and Ethiopian soldiers, burials began over several days, with most funerals taking place on 30 November after people brought the bodies to the churches - often 10 at a time loaded on horse- or donkey-drawn carts.

At Abnet Hotel, the civil servant who spoke to the BBC said some bodies were not removed for four days.

"The bodies that were lying around Abnet Hotel and Seattle Cinema were eaten by hyenas. We found only bones. We buried bones.

"I can say around 800 civilians were killed in Aksum."

This account is echoed by a church deacon who told the Associated Press that many bodies had been fed on by hyenas.

He gathered victims' identity cards and assisted with burials in mass graves and also believes about 800 people were killed that weekend.

The 41 survivors and witnesses Amnesty interviewed provided the names of more than 200 people they knew who were killed.

What happened after the burials?

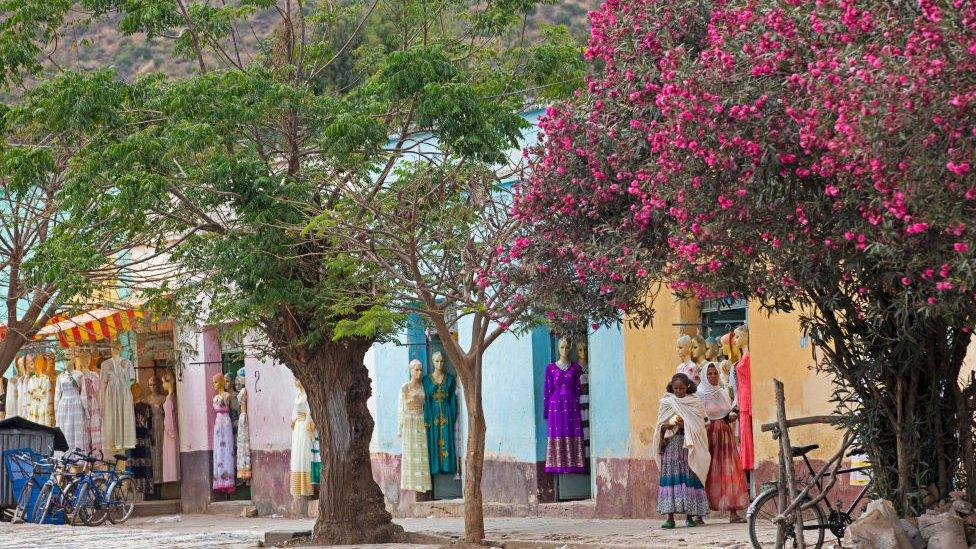

Witnesses say the Eritrean soldiers participated in looting, which after the massacre and as many people fled the city, became widespread and systematic.

What does the future hold for Ethiopia, and what challenges remain in the Tigray region?

The university, private houses, hotels, hospitals, grain stores, garages, banks, DIY stores, supermarkets, bakeries and other shops were reportedly targeted.

One man told Amnesty how Ethiopian soldiers failed to stop Eritreans looting his brother's house.

"They took the TV, a jeep, the fridge, six mattresses, all the groceries and cooking oil, butter, teff flour [Ethiopia's staple food], the kitchen cabinets, clothes, the beers in the fridge, the water pump, and the laptop."

Shops in the city have reportedly been stripped bare

The young man who spoke to the BBC said he knew of 15 vehicles that had been stolen belonging to businessmen in the city.

This has had a devastating impact on those left in Aksum, leaving them with little food and medicine to survive, Amnesty says.

Witnesses say the theft of water pumps left residents having to drink from the river.

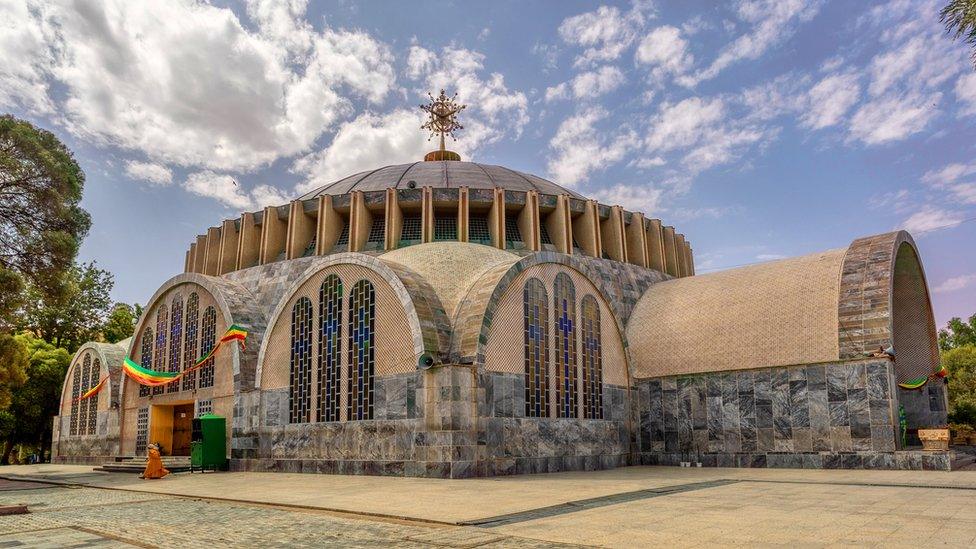

Why is Aksum sacred?

It is said to be the birthplace of the biblical Queen of Sheba, who travelled to Jerusalem to visit King Solomon.

They had a son - Menelik I - who is said to have brought to Aksum the Ark of the Covenant, believed to contain the 10 commandments handed down to Moses by God.

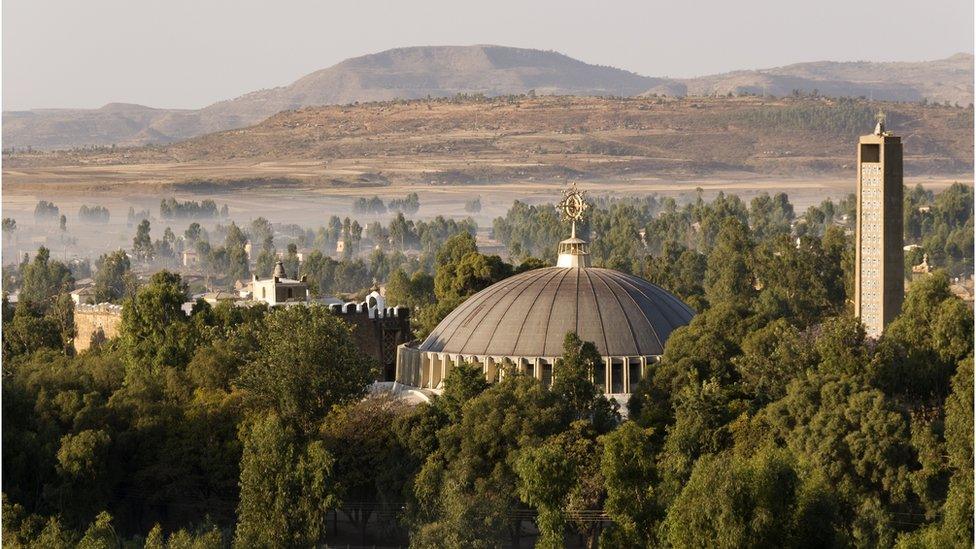

It is constantly under guard at the city's Our Lady Mary of Zion Church and no-one is allowed to see it.

Aksum's Our Lady Mary of Zion Church is a site of pilgrimage for many Ethiopian Orthodox Christians

A major religious celebration is usually held at the church on 30 November, drawing pilgrims from across Ethiopia and around the world, but it was cancelled last year amid the conflict.

The civil servant interviewed by the BBC said that Eritrean troops came to the church on 3 December "terrorising the priests and forcing them to give them the gold and silver cross".

But he said the deacons and other young people went to protect the ark.

"It was a huge riot. Every man and woman fought them. They fired guns and killed some, but we are happy as we did not fail to protect our treasures."

Related topics

- Published24 June 2019

- Published2 January 2024

- Published18 April 2023