Libya's city of ghosts

- Published

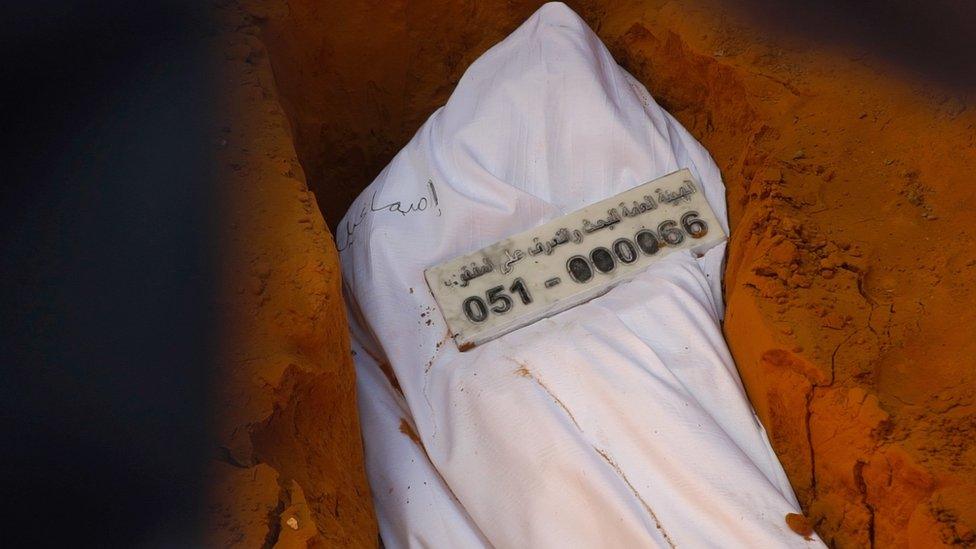

Abdel Manaam Mahmoud lays his brother's body to rest, though he can't be sure he's burying his brother

As the senior man in his family, in fact its only surviving adult male, it falls to Abdel Manaam Mahmoud to climb into the grave and lay his brother Esmail's body to rest. Though it may not be his brother he's burying today.

Around him, the men of Tarhuna gather, pushing the red sandy earth and patting down the mound of dirt with their hands.

Nearby, Mr Mahmoud's father, Hussin, his brother Nuri and his uncle Mohamed are also buried - each a victim of Libya's civil war, casualties of its factional, shifting alliances and all murdered by the same militia who ruled their town.

The bodies were found and buried because of Libya's ceasefire signed last year. Since 2011 and the fall of the dictator Muammar Gaddafi, the country has been roiled by chaos, and later, civil war.

That war reached a crescendo in recent years, as Gen Khalifa Haftar, now aged 77, attacked from the eastern city of Benghazi and tried to unseat the internationally recognised government in the capital, Tripoli.

He had powerful backers: the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Syria, Jordan and France too. His lightning attack on Tripoli became bogged down and was then routed, after Turkey sent a naval force and attack drones to support the government in the east.

Added to this toxic mix were mercenaries from Syria, mostly on the government side, under the control of the Turks. Gen Haftar had his own hired guns - Russian contractors and fighters from Sudan and Chad.

The body count soared, and a country that had reached and passed the brink many times before teetered on the edge of greater catastrophe.

What's behind the fight for Libya? (January 2020)

But a ceasefire was agreed, and for the first time in years, Libya has a unified government. Its prime minister is Abdul Hamid Dbeibah, a fantastically rich businessman from the commercial hub of Misrata. While his family has links to the Muammar Gaddafi rule, little is known about the new prime minister, a political neophyte.

"He was no-one's bête noire," said one Western diplomat in Tripoli, explaining Mr Dbeibah's appointment by a UN-led process that created the interim government. Elections are supposed to be held in nine months, on Libyan Independence Day - 24 December - but already there are doubts.

"It is a tight deadline, but it's not impossible. But of course, again, it starts with all the institutions and authorities of Libya," says Jan Kubis, the UN's special envoy on Libya.

"Either they will deliver what they have to deliver, to make it happen. If not... they will find pretexts, excuses, not to do it... I hope that this will not happen because the people of the country, they would like to have the elections.

"It's not only the proclamations of the authorities and pledges. It's the wish of the people of the country to have the elections on 24 December."

After our interview, Mr Kubis headed to Benghazi to meet Gen Haftar, the man many in Tarhuna believe empowered the seven Kani brothers (whom Mr Mahmoud accuses of killing his relatives) in their final killing spree before they quit town. Some suspect the general is sheltering the surviving brothers, some of whom have been added to US and European sanctions lists.

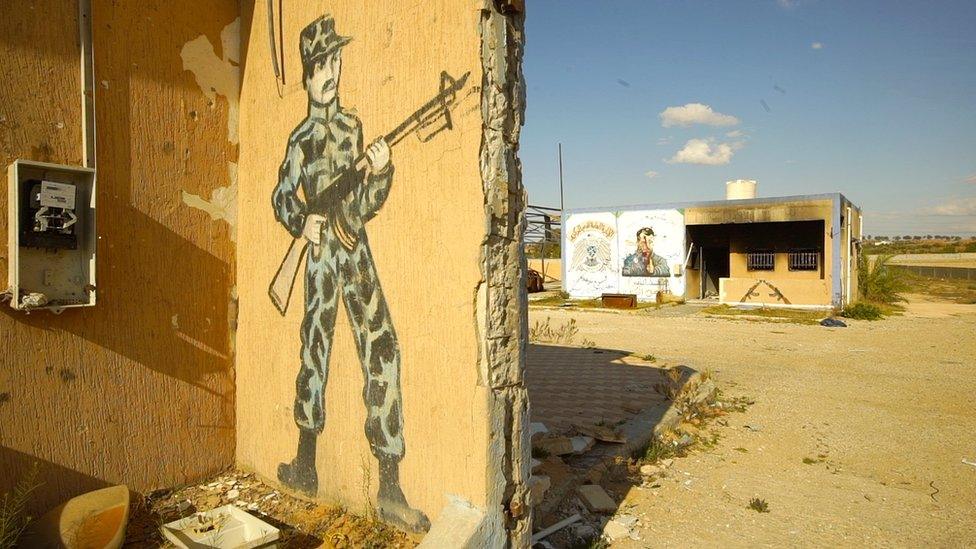

The town of Tarhuna was the western launchpad for the attacks on Tripoli and a flashpoint in the steady internationalisation of the country's civil war.

From here, Gen Haftar's forces from the east, his self-styled Libyan National Army, led assaults on the capital. Mercenaries from Russia's Wagner group took up positions in the town too.

The Kani brothers reigned supreme in the town for years

At the town's cemetery, there are 13 burials today. The men and boys of the town are here in force, they walked in their hundreds after Friday prayers, some using their prayer mats to shade themselves from the afternoon sun.

After the ceremony, Mr Mahmoud said: "They took my family from their homes. They were simple civilians. In October 2020, the al-Kani militia came to their homes in cars that belonged to the state, they took them away from their homes and killed them."

He searched for his family for 10 months, in vain. First the bodies of Hussin, Nuri and Mohamed were found. Two months ago, Esmail's body was discovered.

"Even in his 42 years of ruling, Gaddafi never committed the kinds of killings that occurred after his rule. As Libyan civilians, there is no-one to protect us, our lives have become unprotected," Mr Mahmoud says.

The seven Kani brothers, famous for the three lions they had stolen from the zoo in Tripoli and kept as pets, reigned supreme. Mercurial, their Kaniyat militia switched sides more than once in Libya's civil war.

Their rule came to an end in June last year, when government forces, backed by Turkish support, took the town. Turkey sent seven naval frigates to Libya's coast to push back Gen Haftar's forces, and imported thousands of Syrian fighters from Idlib, Aleppo and Deir Ezzor to fight on the ground.

In the face of the onslaught, the remaining Kani brothers and their families fled east, their whereabouts unknown.

The body of Esmail Mahmoud is identified by a DNA reference number

Tarhuna's cemetery is austere in the Muslim tradition, surrounded by tall thirsty eucalyptus trees and with few headstones; it has only simple grave markers. But Esmail's marker bears a number: 051-000066.

It's a DNA reference. Because the body buried today may not be Esmail's. He was only identified by the clothes he was wearing, when he was discovered in a collection of mass graves to the south of the city.

The road to the farmhouse is surrounded by almond groves. A cardboard sign across the entry, warns: "No Entry, Only Missing Person Committee Allowed."

Beyond the farmhouse, fine red soil is piled in high mounds that stretch to the end of the property. There are too many to count, some the size of a single corpse, others far wider.

It's Friday, so there is no work today and the site is silent, but the evidence of the meticulous effort to uncover the crimes here is all around. In one pit, four red flags mark out the twisted remains of perhaps four bodies, wrapped together, almost unrecognisable.

Men, women and children were buried here, some killed by a single bullet to the head, others with their hands bound with signs of torture on their bodies. The dry earth has left the bodies intact, and swollen. Like artefacts from a terrible disaster.

Esmail's identity will be confirmed when a DNA match is made at a lab in Tripoli. So far, 140 bodies have been found, according to Libya's General Authority for Searching and Identifying Missing Persons. They have confirmed the identities of 22 of the dead by DNA matching.

In total, 350 people are missing from the town, although bodies from elsewhere may be buried here. Across Libya, more than 6,000 people have been declared missing since the downfall of Muammar Gaddafi. Only 1,950 have been found.

At the edge of the cemetery stands Ahmad Abdel-Mori Saad, who's here to bury a friend. Tarhuna is a city of ghosts, he said.

"I have seven siblings who were kidnapped by the Kaniyat. We have buried two of them found in the mass graves," he said.

Mr Saad doesn't know where his other brothers are, but he believes they are dead. He's left to care for all their children, 24 in total.

"We do not follow any political parties; we are not policemen or army men… If you have money, you die; if you have five young siblings, you die; you get in a discussion with me, you die; you don't support me, you die.

"You die for nothing, it's a death for no reason at all."

Related topics

- Published5 February 2021

- Published13 September 2023

- Published23 October 2020