Idriss Déby: Chad's future rocked by president's battlefield death

- Published

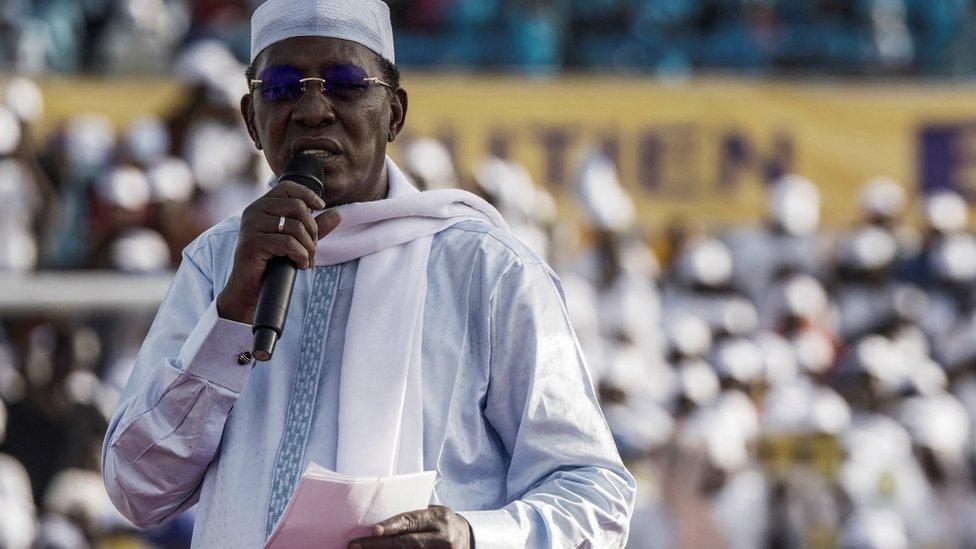

Shortly before his death Idriss Déby campaigned for a sixth term in office

Dying from wounds suffered as he directed the fightback against rebels who had swept south across the Sahara from their Libyan safe haven, Chad's President Idriss Déby Itno was a soldier to the last.

The manner of his death was in keeping with a career that had begun in the officer corps, accelerated by a stint at the École de Guerre defence college in France.

Later, he launched his own revolt, to depose the dictator Hissène Habré in 1990.

Ever since, he had ruled with a strongman's firm hand.

Chad had the formal structures of a multi-party democratic state. But real power was concentrated firmly at the top, and Déby brooked no serious opposition over his three decades in power.

And several times he faced down rebellions, sometimes helped by the military intervention of his ally France - which maintains a major regional base in the Chadian capital N'Djamena.

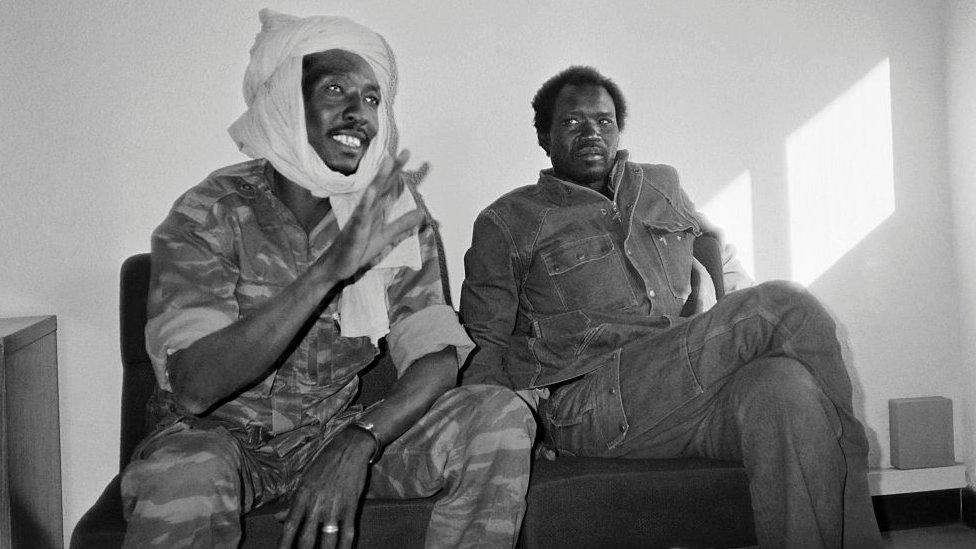

Idriss Déby (L) came to power in 1990 after leading a rebellion against Hissène Habré

In February 2008 it was a particularly close call with the insurgents only stopped at the gates of the presidential palace.

The revolts recurred, often fuelled by rivalries within Déby's own Zaghawa clan, elements of whom established a base in southern Libya - a region outside the control of the government in Tripoli.

This time they broke through further south, reaching Kanem region, north of Lake Chad and just a few hundred kilometres from the capital.

Although government forces have once again proclaimed victory, they have lost their totemic commander.

Huge political figure

His death leaves a gaping question mark.

Contentious certainly, and sometimes brutal, Déby had been a huge figure in the politics and power of west-central Africa.

And that seemed set to continue, following his entirely predictable victory, with 79.3% of the vote, in this month's presidential election. The contest was boycotted by some opponents and several challengers had been excluded.

Now Déby's 37-year old son, Mahamat, hitherto commander of the presidential guard, heads up a self-proclaimed interim military regime that has closed Chad's borders and suspended the constitution.

Chad's President Idriss Déby was one of Africa's longest-serving leaders.

Yet can the old-style Chadian strongman system function and sustain itself in the absence of the redoubtable figure who had created the regime?

Saleh Kebzabo, a leading opposition political voice, has called for dialogue to discuss a route forward and for fresh elections. But there are questions over whether the new leadership would be prepared to contemplate meaningful participation.

Internal politics and rivalries within Déby's Zaghawa clan are also a consideration.

And Chad suffers from deep underlying political, societal and development pressures that had been contained by Déby's forceful rule but certainly not resolved.

At a regional level, his death also poses big questions.

He had built himself into the most significant military actor in the region, deploying forces to assist Nigeria in the campaign against militant Islamist group Boko Haram.

President Déby (second left)) discussed regional security with France's President Emmanuel Macron (second right) and other leaders last year

Chadian troops, with a reputation as tough fighters, were partnered with the armies of Nigeria, Cameroon and Niger, sometimes carrying out cross-border operations against the militants.

Yet while these Chadian interventions had certainly made some impact, the region remained hugely fragile, prey to ongoing violence, with local communities brutally exposed amidst the ongoing conflict.

Meanwhile, further into West Africa, Chad's military clout had earnt Déby a role as one of the principal security actors in the G5 partnership of Sahelian states.

He assigned troops to the UN peacekeeping force in Mali, where they have undertaken some of the toughest desert garrison assignments, and also deployed to support Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger in the highly insecure "three frontiers region" where their borders converge.

Déby also had a long history of influence, both tacit and overt, in Chad's troubled southern neighbour, the Central African Republic.

Looking ahead, there are big uncertainties.

Will the new military regime headed by his son try to sustain the strongman model? Will it seek to strike bargains with other factions amongst the Zaghawa? Or will the leadership try to broaden their political base and open up dialogue about the way forward?

When Déby seized power in 1990 there was no common African stance on the legitimacy of military coups. That has changed.

Africa's demands

Inevitably, the shock of Déby's death has meant that the African Union and other sub-Saharan states will allow this new interim military regime some breathing space to work out the route forwards.

However, in the Africa of 2021 the leadership will eventually need to plot a path back to constitutional rule, with some space for multi-party politics, however constrained.

And on the regional stage, people will be watching to see if the Chadian military feels able to sustain the substantial security commitments that Déby had taken on.

The new government will be aware of the importance of this deployment to its neighbours, as well as to France.

Moreover, the struggle to contain Boko Haram is an issue that directly concerns the security of Chad's own territory and its economic interests.

Related topics

- Published21 April 2021

- Published9 July 2024