Kenneth who? How Africans are forgetting their history

- Published

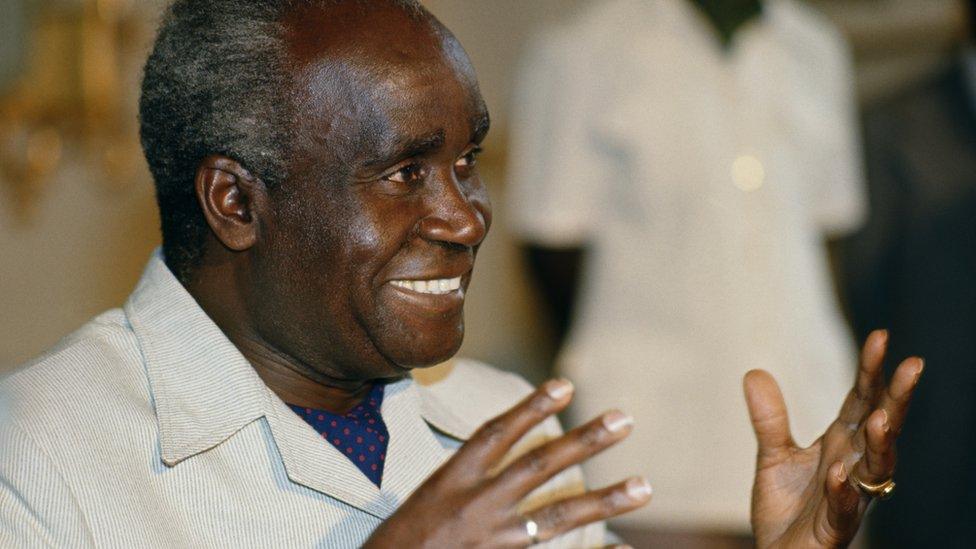

Kenneth Kaunda puts his longevity down to his diet, reportedly saying: "I eat only vegetables, like an elephant"

In our series of letters from African journalists, Sierra Leonean-Gambian writer Ade Daramy considers what young Africans know about their recent history - and why it is important.

I was shocked to find out on the 97th birthday of Kenneth Kaunda - Zambia's first president and a giant in the fight against colonialism - that some people had never heard of him.

I had posted my birthday greeting to the nonagenarian on social media on 28 April with the tag line: "The only African independence leader from the 1960s still alive."

Many celebrated. Other were astonished, saying: "I didn't realise he was still alive."

But to be honest, those under the age of the 30 were clueless.

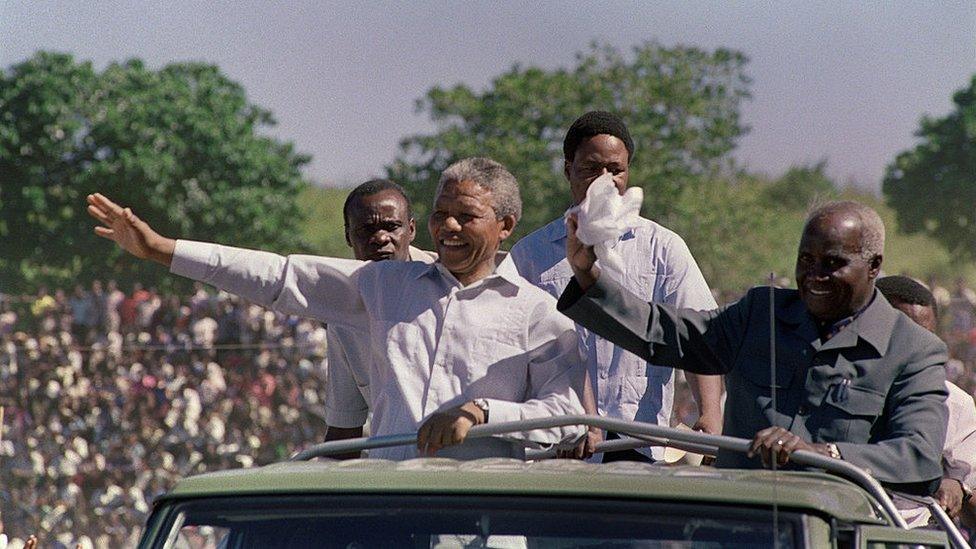

Kenneth Kaunda (R), seen here with a Zimbabwean struggle leader Joshua Nkomo (L), was at the forefront of calls for independence

For someone who grew up in the 1960s in Sierra Leone, this was difficult to fathom.

I was part of a special generation of Africans observing the emergence of colonial states on the continent into independent nations.

UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, fresh from visiting several British African colonies, had delivered his now-famous "Wind of Change" speech in Cape Town to South Africa's all-white parliament on 3 February 1960.

In 1960 UK PM Harold MacMillan (L) signalled that Britain was going to grant independence to its colonies

By the following year, 17 African countries had gained independence.

At school my classmates and I could proudly reel off the names of the leader of every independent African nation, including Milton Margai of Sierra Leone, Dawda Jawara of The Gambia, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Patrice Lumumba of Congo, Ahmed Sekou Touré of Guinea, Modibo Keïta of Mali, Léopold Senghor of Senegal - as well as Mr Kaunda.

Egg and milk promise

Kaunda, the youngest of eight children, was a school teacher before joining the independence struggle.

This is when he became known for his guitar playing, composing liberation songs and travelling the country to drum up support for the campaign against colonial rule.

Kenneth Kaunda famously wields his guitar wherever he goes - here on an official visit to Portugal in 1975

He went on to become Zambia's founding president at the age of 40.

His wish, he said, was for Zambians to have an egg on their table for breakfast every morning, a pint of milk - and for every Zambian to have a pair of shoes on their feet.

Popularly known as KK, during his presidency he was a fierce critic of apartheid South Africa and white-minority rule in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe - and he allowed groups fighting these regimes, like the African National Congress (ANC), to make Zambia their base.

Less than a month after anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela was freed from prison in 1990 he visited Zambia, the home in exile of the ANC

To begin with he made huge strides towards improving the lot of Zambians, but betrayed the promise of democracy by introducing a one-party state in 1973.

Mr Kaunda was the only candidate in elections in 1978, 1983 and 1987 - scoring more than 80% of the vote each time.

He must have been too embarrassed to register 100%.

More on Zambia:

Even within his own party, he changed the rules to keep getting selected as the only candidate.

Eventually, Zambians felt Mr Kaunda had overstayed his time in office and voted him out in 1991 after mass protests forced him to reintroduce multi-party elections.

Dreams forgotten

In the three decades since the rush and joy of independence, the continent had become awash with dictatorships - which may explain why some of its post-colonial leaders are no longer remembered by a younger generation.

Some were assassinated or deposed in coups, others had forgotten the dreams of people and the promises made to them.

Africa still has leaders who have been in power for more than 20 or 30 years.

It makes me wonder what is taught in African history classes today"

Some have been in power for almost 40 years, like Cameroon's President Paul Biya. He is only the second president Cameroon has had since independence from France in the 1960s.

Perhaps it is because of this legacy that men who should be lionised are largely forgotten.

And it makes me wonder what is taught in African history classes today.

Surely Mr Kaunda - who since leaving office has largely kept out of politics and has devoted much of his energy to fighting HIV after losing one of his sons to Aids in the late 1980s - is someone who ought not to be forgotten.

He is a living reminder of the continent's history - good and bad - and we can learn from both.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

Related topics

- Published24 March 2023