DR Congo: Measles vaccines missed because of Covid focus

- Published

With many children missing out on measles vaccines because of disruption caused by the coronavirus pandemic, fears are growing that there could be an outbreak of the disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

"In the last two to three months we've not been able to carry out routine measles vaccinations, which is worrying," says Eugénie Ngabo Nzigire, a nurse based in the eastern city of Bukavu.

"It takes just one sick child and the whole community is in danger," adds the 57-year-old head of the maternity unit at Skyborne Hospital.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has warned that with an estimated 140 million measles vaccinations around the world having been missed due to Covid-19 disruption, countries with fragile healthcare systems, such as DR Congo, could be sitting on a "time bomb" of potential outbreaks.

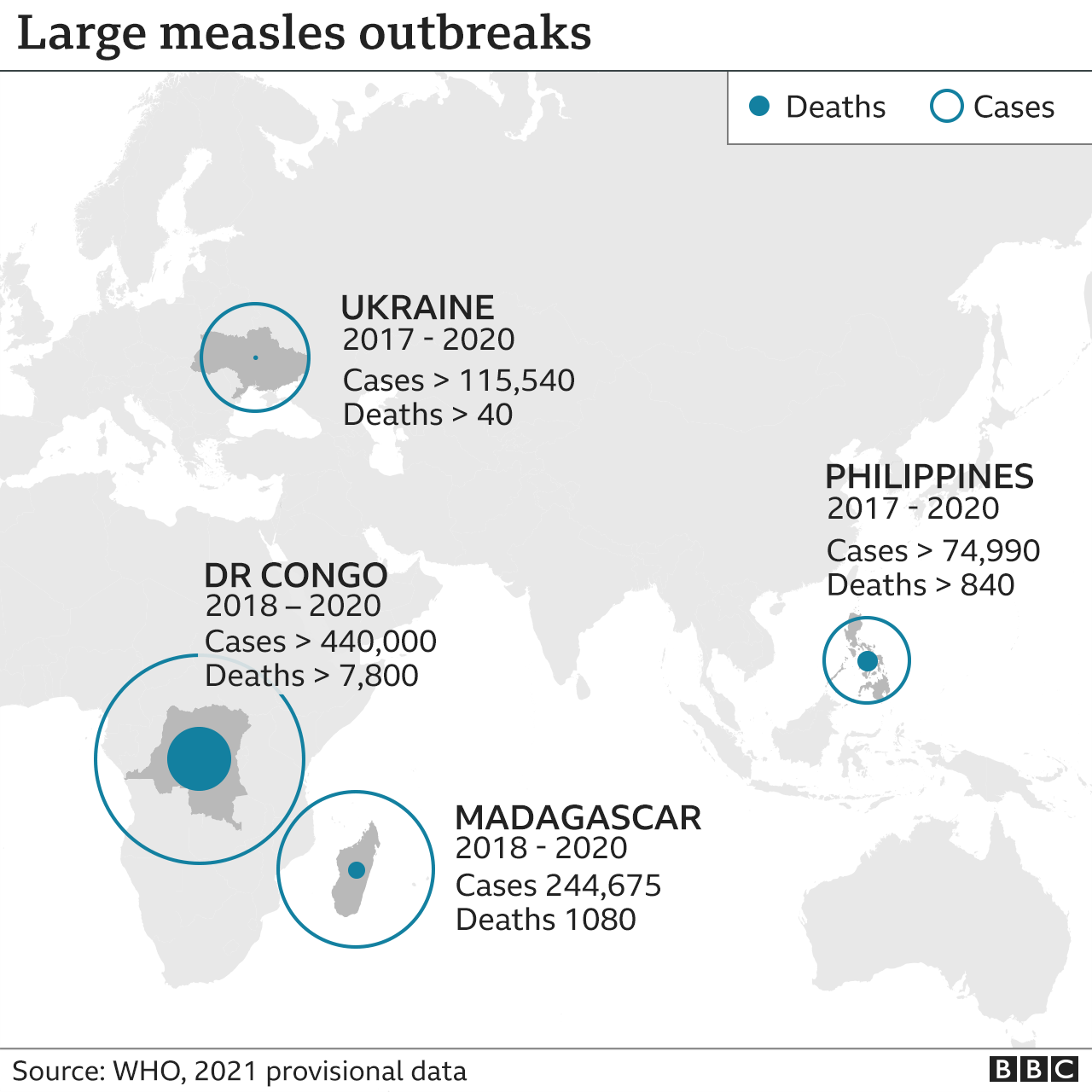

DR Congo reported 440,000 cases in its last measles outbreak, which ended in September.

DR Congo is currently experiencing a surge in Covid-19 cases

Nearly 8,000 people - mainly children - died from measles between 2018 and 2020 in the country, according to monitoring data from the WHO.

Measles is the most infectious preventable disease in the world, much more contagious than Covid-19. It is spread through contact and droplets that can remain in the air for hours.

Still a common killer, there are outbreaks currently in Pakistan and Yemen as well as concerns that there could be one in the Tigray region of Ethiopia.

"A child can get measles and die wherever they are in the world, but the likelihood of death is much higher for children younger than one and if there are other stresses like malnutrition or vitamin A deficiency, these really increase the risk of death," says Dr Natasha Crowcroft, senior technical advisor for measles and rubella at the WHO.

I knew I wanted to be a nurse at a very young age, so it's not just a job that I fell into but a vocation to care for people"

Bukavu is a bustling commercial centre and home to around a million people.

It is also where Ms Ngabo Nzigire has dedicated more than three decades of her life to treating children.

"I knew I wanted to be a nurse at a very young age, so it's not just a job that I fell into but a vocation to care for people," says the mother of 11.

Ms Ngabo Nzigire found her calling unexpectedly when she became very ill and had to be hospitalised at the age of 12.

"I remember the nurse treating me was using an old mercury thermometer that you had to shake before taking the temperature," she says. "I was fascinated by it and thought: 'This is what I want to do with my life'."

The most recent four major outbreaks of measles

The city is also a distribution hub for vaccines, which arrive from the capital Kinshasa, before being sent out to nearby smaller towns such as Bunyakiri.

"It's been four months since we have had measles vaccines available, and we've had other vaccine shortages at the same time," says Marocain Chumac Buroko, a supervising nurse in Bunyakiri.

Fearing vaccines

Bunyakiri is located within the "red zone", an area in the east of the country plagued by decades of insecurity and violence.

Trust, says Mr Buroko is critical to his work, "because people are living with trauma".

But recently fake news and rumours about Covid vaccines have resulted in some families refusing to vaccinate their children completely.

"Many in the community were worried when the news of Covid-19 first emerged. People were told that the vaccine [for Covid-19] would be included along with other routine vaccines, so parents didn't want to vaccinate their children from all other diseases out of fear," says Mr Buroko.

The city of Bukavu has limited health facilities

Regarding regional shortages, the authorities declined to comment.

However aid agencies say it is due to a lack of investment.

"In the last few months, there was a shortage of some vaccines paid for by the government. Measles vaccinations weren't stopped, but there was a slowdown in immunisation programmes," says Thomas Noel Gaha from the UN children's agency Unicef in DR Congo.

A life-saving dose

It's not only DR Congo that's been affected by the pandemic.

Many countries have fallen behind with critical vaccination programmes, threatening the health of an estimated 228 million people, external - mostly children - at risk of diseases such as polio, yellow fever and measles.

Of the more than 20 countries which temporarily halted their measles vaccination campaigns entirely last year, 15 were in Africa.

"Despite the falling routine vaccine coverage in the first two quarters of last year, many countries managed to make up ground. But we don't know whether all children in the first half were ever reached,'' says Dr Crowcroft.

"Many of us in the measles field are really concerned that we're sitting on a time bomb with some countries," she says.

The World Health Organization recommends two measles vaccine doses for optimum protection in children

Prior to the pandemic, in 2019 measles infections surged worldwide reaching the highest number of reported cases in 23 years - resulting in nearly 208,000 deaths, external.

Experts say the high number of cases and death toll were mainly fuelled by a failure to vaccinate children on time with the recommended two doses of the vaccine.

However in countries like DR Congo, where there is conflict, weak healthcare systems and limited resources, even providing a single dose to every child in the country under the age of five is a struggle.

"Children are normally vaccinated against measles at nine months here [DR Congo] with a single 0.5ml injection," says Ms Ngabo Nzigire.

Critically, says Dr Crowcroft, measles prevention relies on herd immunity, whereby the large majority of the population is immune, reducing the chance the virus can spread to those who are the most vulnerable.

But in DR Congo, with one of the highest birth rates in the world, external, this is very difficult to achieve. Just one unvaccinated child risks passing the virus on to the next generation of new-borns.

DR Congo is one of nearly 50 countries at risk of a severe measles outbreak in the next few years, according to the WHO.

"Every measles death is a preventable death," says Dr Crowcroft.

"Outbreaks are a sign that something has gone wrong, so we are pushing for countries to be prepared ahead of what we think is coming," she adds.

BBC photographs by Raïssa Karama Rwizibuka