Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue and his love of Bugattis and Michael Jackson

- Published

Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue in 2012

For years the fortunes of Teodoro "Teodorin" Nguema Obiang Mangue mirrored those of his country, Equatorial Guinea, as it rose to become one of sub-Saharan Africa's biggest oil producers.

The son of President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo enjoyed a lavish lifestyle in California and France.

His good times abroad contrasted starkly with the lives of most of his fellow citizens, who saw little trickle-down from the oil revenue.

Now the funding for his lifestyle has been exposed as embezzlement, as Teodorin faces a criminal conviction in France, sanctions in the UK and a record for corruption in the US.

But back home the 52-year-old remains vice-president, in pole position to succeed his father, 79.

'Relentless embezzlement and extortion'

Teodorin spent time in California as far back as 1991 when he enrolled at Pepperdine University in Malibu.

He eventually bought a $30m mansion in Malibu and his other assets in the US included a Ferrari car and Michael Jackson memorabilia.

This came out in 2014 when the US justice department forced him to surrender the assets in a settlement after finding he had paid for them in a "corruption-fuelled spending spree".

"Through relentless embezzlement and extortion, Vice President Nguema Obiang shamelessly looted his government and shook down businesses in his country to support his lavish lifestyle, while many of his fellow citizens lived in extreme poverty," said Assistant Attorney General Caldwell in a statement, external.

Money from the sale of the assets was meant to "be used for the benefit of the people of Equatorial Guinea".

'No longer a haven'

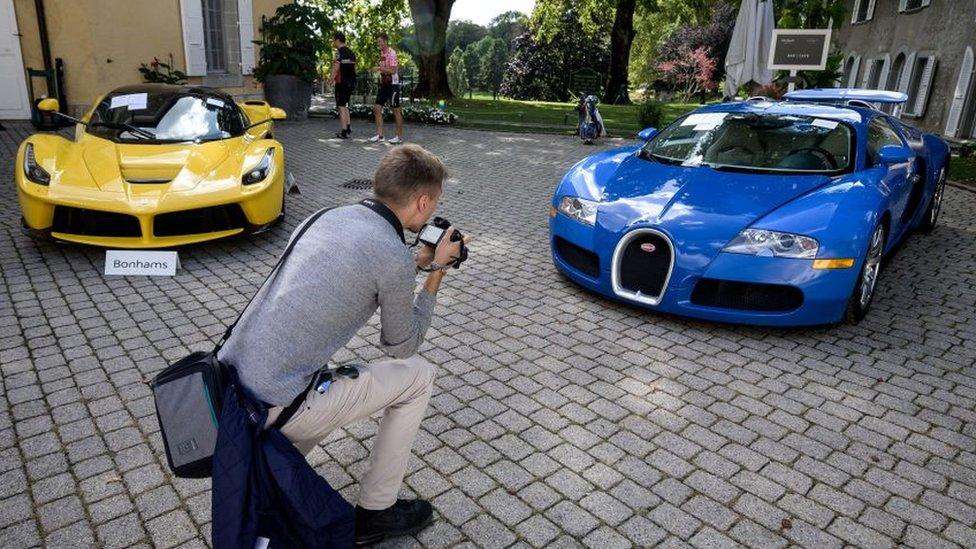

In 2016, Swiss prosecutors seized 11 luxury cars belonging to him. The cars - among them a Bugatti, Lamborghinis, Ferraris, Bentleys and Rolls Royce - were sold at an auction for about $27m.

Sports cars owned by Equatorial Guinea's vice-president were auctioned in Switzerland

Some $23m was to go to social projects in Equatorial Guinea.

Then, in 2017, it was France's turn to clamp down on Teodorin when a court convicted him of embezzlement and ordered the seizure of his assets in the country.

He was given a three-year suspended sentence in absentia and a 30m euro fine, and his luxury assets in France were seized. One of his seized properties in Paris is worth over $120m.

Under a French law all this wealth is to be redistributed to the people of Equatorial Guinea.

The judgment was upheld by the top appeals court, which rejected his protestations of innocence and his argument that French courts had no right to rule on his assets.

"With this decision... France is no longer a haven for money embezzled by senior foreign leaders and their entourage," Patrick Lefas of Transparency International France, which was party to the case, said in a statement, external (in French).

Finally, last week the UK slapped "anti-corruption" sanctions on Teodorin and four other figures from Zimbabwe, Venezuela and Iraq.

Michael Jackson's "Bad Tour" glove was auctioned in Beverly Hills, California, in 2010

The UK said his collection of Michael Jackson memorabilia included a $275,000 crystal-covered glove which the later singer had worn on his 1980s Bad tour.

The sanctions will see the UK impose asset freezes and travel bans to prevent named individuals channelling money through UK banks or from entering the country.

UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab said the new sanctions targeted individuals who had "lined their own pockets at the expense of their citizens".

A warning to others

Despite his legal troubles abroad, Teodorin keeps his place at the top of Equatorial Guinea's political establishment.

His father is Africa's longest serving leader and has been described by human rights organisations as one Africa's most brutal dictators.

While the president himself is the key figure, his son is "relatively well known as a personality in west and central Africa given the international media coverage he has attracted", says Africa analyst Paul Melly.

"The action that has been taken by judicial authorities in some European countries against alleged corruption by some African presidential families is a sign of the risk of potential damage to credibility and access to development funds that some regimes might face," he adds.

"But such cases are very much not typical of today's sub-Saharan Africa."