Kenya's Deputy President Ruto campaigns for 'Hustler Nation'

- Published

William Ruto has been giving out wheelbarrows to youths

From pushing wheelbarrows to making much of the fact that he was a chicken seller in his youth, Kenya's Deputy President William Ruto is increasingly framing next year's general election as a contest between "hustlers" and "dynasties".

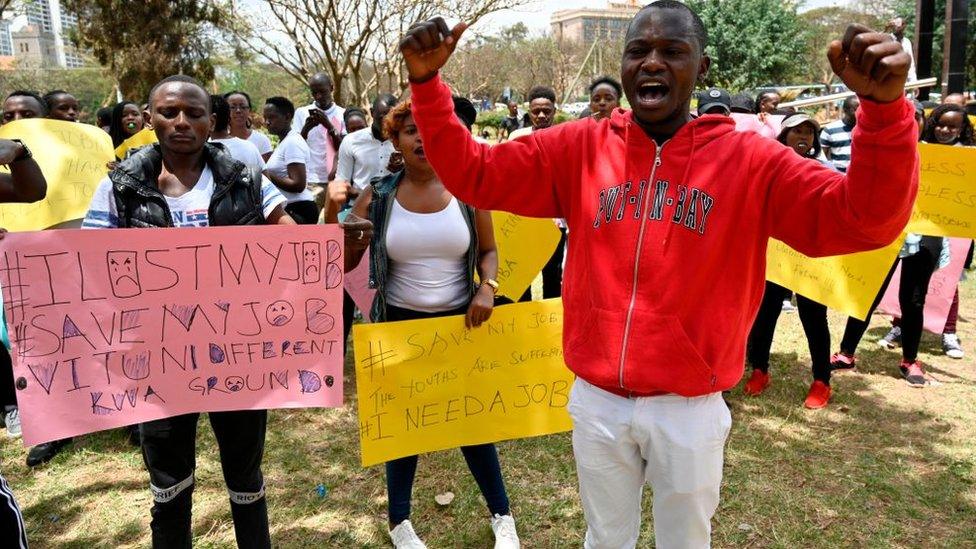

In Kenya, hustlers refer to those - especially young people - who struggle to make ends meet in an economy that is said to be no longer working for them.

The word dynasties, on the other hand, is a moniker to describe wealthy families that are seen to have dominated politics - and the economy - since independence from the UK in the 1960s.

President Uhuru Kenyatta and opposition politician Raila Odinga have been put in the latter category.

They are the sons of the country's first president and vice-president respectively, although Mr Odinga holds the record for being Kenya's longest-serving political detainee and has been instrumental in the fight for political reforms.

The phrase "Hustler Nation" was coined by Mr Ruto, a 54 year-old combative and ambitious politician.

He has spoken of how he went to school barefoot, getting his first pair of shoes at the age of 15, and how he once "hustled by selling chickens by a roadside".

Political divorce

These days Mr Ruto has been giving out wheelbarrows, handcarts and water tanks to the unemployed, which is endearing him to many young people.

Youth unemployment stands at almost 40% in Kenya

He formed an alliance with Mr Kenyatta in the 2013 and 2017 elections, propelling the two of them to power.

The alliance was viewed by many as a union of convenience between two men whose backgrounds couldn't be more different.

The pair have since fallen out, but Mr Ruto still remains in office, courtesy of constitutional provisions that secure the tenure of a deputy president.

He hopes to rise to the presidency next year, in an election that could see him pitted against the 76-year-old Mr Odinga, who - in a sign of the shifting political sands in Kenya - is now in an alliance with Mr Kenyatta.

The two have countered Mr Ruto's campaign by promoting the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), which revolves around constitutional changes aimed, they say, at improving governance.

This includes creating the post of prime minister. It fuelled speculation that Mr Kenyatta hopes to take the post in an Odinga-led government.

But in a major blow to the duo, the Appeals Court last week upheld a High Court ruling that BBI was illegal, saying that only parliament - not the president - could initiate the process of amending the constitution. The government has indicated that it will appeal against the ruling in the Supreme Court.

'Deepening divisions'

Mr Ruto - who also rallied support in the last election under the "Hustler Nation" slogan - is now using it to promote a "bottom-up" approach to the economy, saying it will benefit the poor, especially the youth, who are bearing the brunt of the downturn largely triggered by the coronavirus pandemic.

Deputy President William Ruto harbours presidential ambitions

The official rate of unemployment among those aged between 18 and 34 years is nearly 40%, and the economy is not creating sufficient jobs to absorb the 800,000 youths joining the workforce every year.

Critics have dismissed Mr Ruto's "bottom-up" idea as full of "hackneyed clichés".

"It only seems as if the plan is to dish out money to the common people. That doesn't sound like a sound economic idea or plan," says historian Ngala Chome.

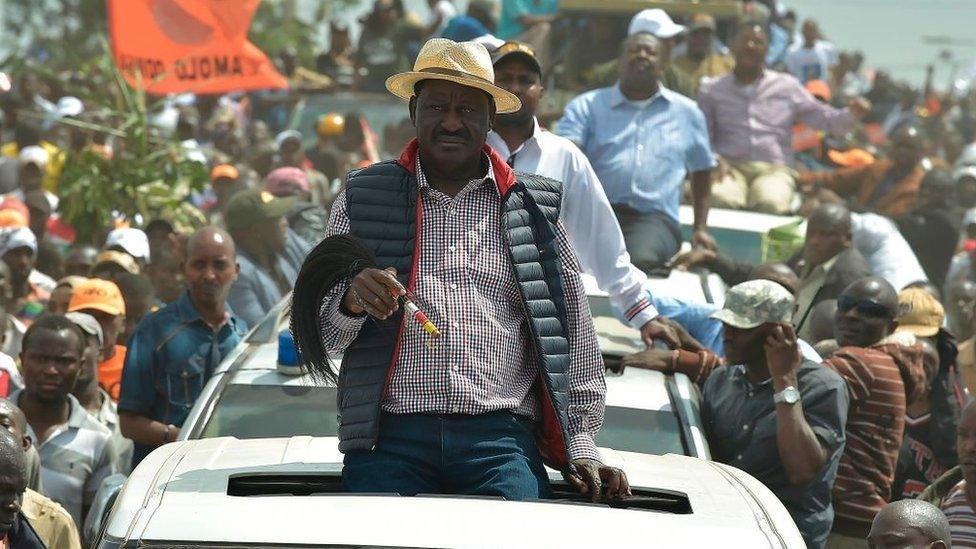

Mr Odinga, who has failed in four previous bids for the presidency, has described Mr Ruto's proposal as "rubbish", saying economic growth cannot be achieved without steps being first taken to guarantee political stability and good governance.

The National Cohesion and Integration Commission, a state body mandated to promote national unity, previously warned that continuing with the "hustlers v dynasties" line risked deepening class divisions and plunging the country into chaos.

Veteran opposition politician Raila Odinga is expected to run for the presidency next year

There is no doubt that Mr Ruto's focus on the "Hustler Nation" has triggered debate about Kenya's harsh political reality since independence.

"The same political elite that gained power after the colonialists left is the same elite that is still in power. That's a very crucial aspect of trying to understand Kenya's politics," says Mr Chome.

Mr Ruto's focus on this is strengthening his standing among the young and the poor. Candidates he endorsed have won three recent parliamentary by-elections.

His campaign has so far largely avoided playing the ethnic card - something that is normally a big mobilising tool and has caused unrest in previous elections.

"There is a shift in Kenya's politics. People are now talking about the economy in a campaign in a way that they have not done before," says Mr Chome.

Glitzy campaign

There are still questions being raised over Mr Ruto's claim that he stands for change.

He has been linked to corruption scandals in government and the source of his wealth is a subject of debate.

In June 2013, the High Court ordered him to surrender a 100-acre (40-hectare) farm, and compensate a farmer who had accused him of grabbing the land during the 2007 post-election violence.

Violence has marred some of Kenya's previous elections

He insists he is clean and says his immense wealth has been painstakingly acquired through hard work.

The question of finance is important, because Kenyan politics is an expensive affair - candidates spend thousands of dollars, with no guarantees of success.

The "Hustler Nation" campaign waged by Mr Ruto and his allies has been glitzy, suggesting access to a substantial budget.

A study on campaign financing released in July, external found that levels of spending were "a major contributor to the outcome". The lack of regulation also means that voters can be bribed, and the outcome of elections influenced.

Mr Chome sees Mr Ruto's campaign as "a struggle between old and new money".

"This new younger generation - that is now being referred to as the 'hustler generation' - is not proposing a serious relooking at Kenyan politics," he says.

They are merely "asking for space to be included in governance".

You may also be interested in:

Related topics

- Published4 July 2023