Paul Rusesabagina: From Hotel Rwanda hero to convicted terrorist

- Published

Paul Rusesabagina refused to appear in court for much of his trial

Paul Rusesabagina, the subject of Oscar-nominated film Hotel Rwanda portraying his life-saving actions during the Rwandan genocide, is now facing many years in prison for terror-related crimes.

Nearly two decades ago he presented himself as an ordinary man who happened to be caught up in extraordinary times.

The Rwandan former hotel manager, 67, is credited with saving the lives of more than 1,000 people during the genocide.

Over the course of 100 days, starting in April 1994, about 800,000 people, mostly ethnic Tutsis were massacred by extremists from the Hutu community.

As Rusesabagina, a Hutu married to a Tutsi, described in his autobiography, An Ordinary Man, it was his ability to persuade the killers against targeting those who had sought refuge in the Hotel Mille Collines that spared them.

He was also able to use his connections and call in favours with some of the high-profile people who used to pass through the upmarket hotel. In addition he had cash.

In one passage he writes about the hotel being surrounded by "hundreds of [militia] holding spears, machetes, and rifles" shortly after he was told he had to evacuate the building.

"It would be a killing zone... in an hour," he concluded. He then got on the phone and spoke to as many senior officials as he could, one of whom called off the attack.

He always maintained that it was what he said that made the difference.

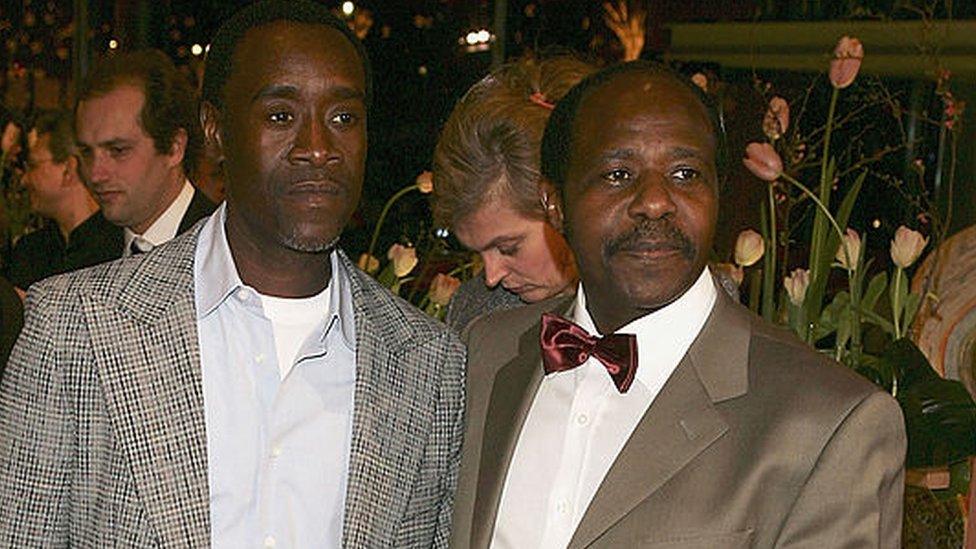

Don Cheadle (L) played Rusesabagina (R) in the film Hotel Rwanda

Words can be "powerful tools of life", he wrote in his 2006 book, but now they have landed him in prison.

Rusesabagina, who left Rwanda in 1996, went from hero to enemy of the state in a short time as his criticism of the post-genocide government grew louder. It gradually morphed into calls for regime change.

In a video message in 2018, he was recorded as saying that "the time has come for us to use any means possible to bring about change in Rwanda. As all political means have been tried and failed, it is time to attempt our last resort".

By that point he was the leader of an opposition coalition in exile, the Rwanda Movement for Democratic Change (MRCD). Its armed wing, the National Liberation Front (FLN), had been accused of carrying out attacks in Rwanda earlier in 2018.

Taxi driver in Belgium

Rwanda's government, under President Paul Kagame, has a reputation for dealing harshly with opponents in exile.

Mr Kagame, a Tutsi, led the forces that ended the slaughter and later went on to become president.

A number of his critics have been killed, or attempts have been made on their lives, but the government has always dismissed suggestions that it was involved.

Rusesabagina had long complained of harassment from Rwandan agents. In 2009, he left Belgium, where he had settled with his family, for the US after his home was burgled several times and important documents were stolen.

His journey to pariah status began after the film Hotel Rwanda was released in 2005.

Rusesabagina's story had remained largely unknown for a decade, while he worked as a taxi driver in the Belgian capital, Brussels.

It was featured in a section of journalist Philip Gourevitch's 1998 book about the genocide, but it was the Hollywood movie, where he was played by Don Cheadle, that brought him global attention.

Rusesabagina was then given several awards including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the US' highest civilian honour, by George W Bush in 2005. "His life reminds us of our moral duty to confront evil in all its forms," read the citation.

US President George W Bush awarded Rusesabagina for his role in sheltering people during the Rwandan genocide

The movie's premiere in his home country was in front of 10,000 people in a stadium in the capital, Kigali, which Rusesabagina was expected to attend.

But he never travelled to Rwanda. The official explanation was that he was unwell but the screening came at a time when he was saying that Hutus were now being targeted by the Tutsi-led government.

An Ordinary Man was then published in 2006.

In it he described his early life in rural Rwanda in idyllic terms. He was one of nine children from a Hutu father and a Tutsi mother.

He went on to talk about what happened during the genocide, but there was a sting in the tail.

Towards the end, he described President Kagame as the "classic African strongman" adding that "the popular image persists that Rwanda is today a nation governed by and for the benefit of a small group of elite Tutsis".

'Manufactured hero'

His prescription at the time, for the man who loved the power of words, was talking and he urged dialogue to help sort the country's problems out.

But Rusesabagina's reputation in Rwanda was crumbling. The state-run media started criticising him and Mr Kagame called him a "manufactured hero" in what some saw as a deliberate attempt to destroy the reputation of someone who dared to challenge him.

Some of the survivors began to contradict Rusesabagina's account.

In exile, he became more outspoken about what he saw as the targeting of Hutus. His backers have described him as a human rights defender calling out an oppressive government.

In 2007, Rusesabagina said a UN-backed war crimes court should put some members of Mr Kagame's party on trial for their alleged role in the genocide.

In a 2014 speech at the University of Michigan, he said that proxy groups operating on behalf of the Rwandan government had killed hundreds of thousands of Hutu refugees in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

A 2010 UN report had revealed some of the details, but the Rwandan government rejected it, calling it "flawed and dangerous".

'Kagame is the only judge'

The rhetoric may have been grating for Mr Kagame, but it was Rusesabagina's links to the FLN, which had carried out attacks in Rwanda, that gave the authorities grounds to arrest him.

However his detention in August last year was highly controversial.

His family said that he had been abducted in Dubai and taken by force to Rwanda.

But in another version of events, described in court, former ally Constantin Niyomwungere said he had tricked him onto a plane by making him believe that he would be flying to Burundi.

President Kagame said he was not forced to go to Rwanda and compared Rusesabagina's journey to dialling a wrong number, adding that the process was "flawless".

Rusesabagina's family have also alleged that his basic human rights were violated in detention as he was held in solitary confinement and had limited access to his lawyers.

Once in court Rusesabagina did not deny a connection to the FLN.

"We formed [it] as an armed wing, not as a terrorist group as the prosecution keeps saying. I do not deny that the FLN committed crimes but my role was diplomacy," he argued. He also said that he never asked anyone to target civilians.

But earlier this year, he decided to withdraw from the trial arguing that he was not getting a fair hearing.

"He is a political prisoner," his daughter Carine Kanimba told the BBC, adding that "Paul Kagame is the only judge in the court" saying that he has had a "personal vendetta" against her father.

As a result the guilty verdict came as no surprise to Ms Kanimba, and the court was one forum where Rusesabagina's ability to use words to persuade people would not work.

Find out more about the Rwandan genocide:

Between April and July 1994, an estimated 800,000 Rwandans were killed in the space of 100 days.

Related topics

- Published7 April 2019