Maasai Mara safari overcrowding stresses Kenyan wildlife

- Published

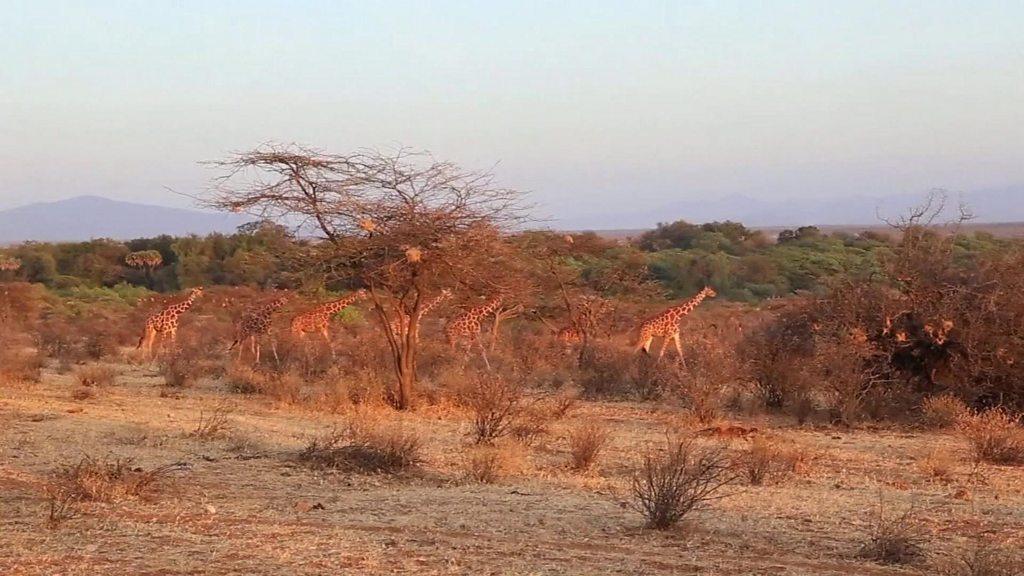

An early morning in Kenya's Maasai Mara game reserve - with wildebeest quietly grazing, birds crowding on the branches of a lone acacia tree and some zebras meandering nearby - is suddenly interrupted by an incoming radio call.

Our tour guide driving a four-wheel drive speeds off across the plains after being told the famous "four brothers" are on the prowl.

These male cheetahs are known to work together with deadly efficiency - although, with so many wildebeest in the vicinity, it is hard to imagine breakfast will present much of a challenge.

Ours isn't the only four-wheel drive racing across the dry grass to witness the imminent kill. No fewer than 27 other vehicles are encircling the herd of zebra and wildebeest waiting for the show.

When the four cats finally spring on their hapless prey and bring one young wildebeest to the ground, about half the cars pull up around them to watch. Each car carries a group of tourists, cameras in hand, filming the cheetahs' jaws on the wildebeest's neck and recording the animal's last mournful cries.

The kill is what many tourists come to see. The harsh brutality of the animal kingdom played out on the African savannah.

Tourists pay good money to see a kill

Few would say they came to see swarms of other tourists, charging off to the next sighting, or that they enjoyed the backdrop of parked Land Rovers in their best shots; but for many that is what a trip to the Mara has become.

Last month, the Narok County government re-issued a set of rules to guides that must be adhered to when taking tourists on game drives.

It comes after a group of visitors and their camp were banned from visiting the Mara indefinitely in July, after a video shared widely on social media showed a man filming a leopard cub at the open door of his car.

The rules state vehicles must be at least 25m (82ft) away from cat species and drivers must not form a circle of cars around the animals, who need to be able to assess the environment for potential danger.

When they pay the money, most clients, if they didn't see a lion or an elephant - the 'Big Five' - they assume they didn't see anything"

There is also supposed to be a maximum of five vehicles at a sighting at any one time - but this is commonly ignored.

Being caught breaking the rules can incur an on the spot fine, immediate removal from the Mara or a ban from future visits.

But enforcing the rules in a 1,500-sq-km (579-sq-mile) park is not easy and John Ole Tira, chairman of the Mara Guides Association - a voluntary group with 175 members - says there is also the problem of managing tourists' expectations.

"When they pay the money, most clients, if they didn't see a lion or an elephant - the 'Big Five' - they assume they didn't see anything."

The "Big Five" - lion, elephant, buffalo, rhinoceros and leopard - is a term originally coined by game hunters of the most difficult animals to kill.

'Ferrari safari'

Phoebe Mottram, a South Africa-based British conservationist who used to work as a safari guide, says although it now refers to spotting and not shooting animals, the notion of the Big Five remains problematic.

Guests want to see what they're told they should see, and most guides survive off tips, because their salaries aren't good enough"

"It comes down to marketing," she says.

"Guests want to see what they're told they should see, and most guides survive off tips, because their salaries aren't good enough.

"So the guide chases the Big Five, gets better tips and this creates a perpetuating cycle."

She and her partner Lawrence Steyn, another former guide, recently launched an online platform that aims to connect tourists with ethical safari camps and guides, called Thatch and Earth.

"You have a responsibility where you put your money," says Mr Steyn.

While answering radio calls of animal sightings is part of the job, guides should be educating clients about appreciating the ecosystem as a whole, instead of racing to tick off a list of five animals, he says.

"We call that a Ferrari safari," he says. "It's South African slang for people who just go really quickly from the buffalo to the elephant to the rhino and then they go home and call that a great day."

'Serengeti is more relaxed'

Romina Facchi, who runs the website Exploring Africa, warns that if guides continue to put pressure on animals by overcrowding them, the animals may become harder to find.

"If the animals feel stressed, they could decide to move away from the cars," she says.

Research shows cheetahs living in parts of the Maasai Mara crowded with vehicles raise fewer cubs

Some may even choose to avoid the annual migration from the Serengeti to the Mara - one of the biggest wildlife attractions in Africa, when more than a million animals migrate in search of fresh pastures.

"In some seasons, when the rains are copious, some hartebeest [antelope] herds decide to stay in Tanzania and don't cross the Mara River to go to Kenya because they don't need to: they prefer to stay in a more relaxed environment."

A 2018 study showed that cheetahs living in parts of the Maasai Mara with a high density of tourist vehicles raised fewer cubs than those in low tourist areas - a worrying trend for a species with only around 7,000 mature animals left in the wild.

By dung, by air and by sea... Kenya conducted the biggest animal count ever

The first ever Kenyan wildlife census, carried out earlier this year, found that while populations of some endangered animals are gradually increasing, such as the black rhino and elephant, others, such as the roan and sable antelope, risk becoming extinct, with just 15 and 51 respectively left in Kenya.

Jerome Gaugris, an ecologist who runs an environmental consultancy in South Africa, says it comes down to educating guides and tourists.

He says vehicle limits that have become standard practice in private South African game reserves for years should be enforced in Kenya, though he admits it is harder to do so on public land where different guides, operators and agencies work.

"We limit it to four vehicles at a sighting at any one time," says André Burger who runs the Welgevonden Game Reserve in South Africa.

"It's not all about the Big Five."

Related topics

- Published1 September 2020

- Published29 December 2020