Mozambique: Tuskless elephant evolution linked to ivory hunting

- Published

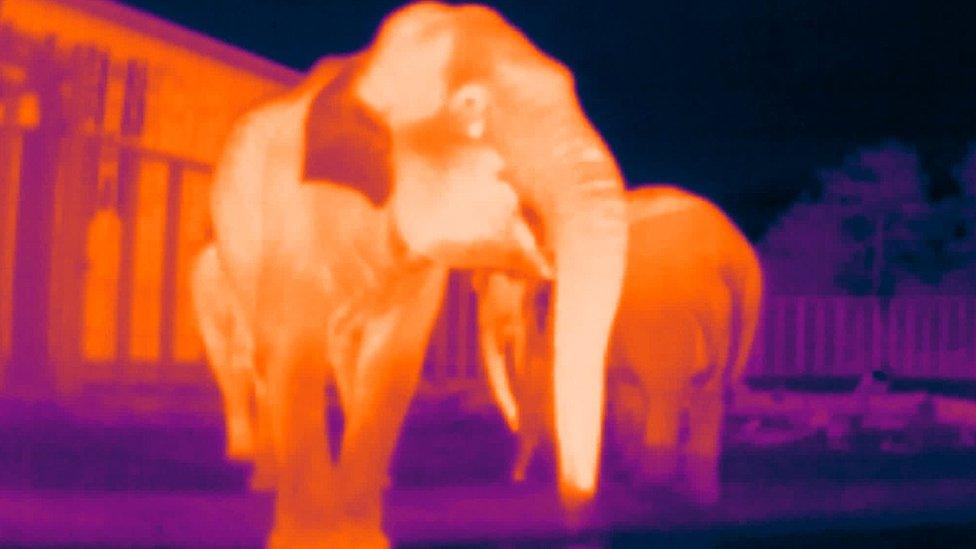

African elephant herd with tuskless matriarch.

A new study suggests that severe ivory poaching in parts of Mozambique has led to the evolution of tuskless elephants.

The study published in Science magazine, external found that in Gorongosa National Park a previously rare genetic condition had became more common as ivory poaching used to finance a civil war pushed the species to the brink of extinction.

Before the war, about 18.5% of females were naturally tuskless.

But that figure has risen to 33% among elephants born since the early 1990s.

Some 90% of Mozambique's elephant population was slaughtered by fighters on both sides of the civil war that lasted from 1977 to 1992. Poachers sold the ivory to finance the vicious conflict between government forces and anti-communist insurgents.

As in eye colour and blood type in humans, genes are responsible for whether elephants inherit tusks from their parents.

Elephants without tusks were left alone by hunters, leading to an increased likelihood they would breed and pass on the tuskless trait to their offspring.

Researchers have long suspected that the trait, only seen in females, was linked to the sex of the elephant. After the genomes of tusked and tuskless elephants were sequenced, analysis revealed that the trend was linked to a mutation on the X chromosome that was fatal to males, which did not develop properly in the womb, and dominant in females.

The study's co-author, Professor Robert Pringle of Princeton University, pointed out that the discovery could have a number of long-term effects for the species.

He noted that because the tuskless trait was fatal to male offspring, it was possible that fewer elephants would be born overall. This could slow the recovery of the species, which now stands at just over 700 in the park.

"Tusklessness might be advantageous during a war," Professor Pringle said. "But that comes at a cost."

Another potential knock-on is changes to the broader landscape, as the study has revealed that tusked and tuskless animals eat different plants.

But Professor Pringle emphasised that the trait was reversible over time as populations recovered from the brink of elimination.

"So we actually expect that this syndrome will decrease in frequency in our study population, provided that the conservation picture continues to stay as positive as it has been recently," he said.

"There's such a blizzard of depressing news about biodiversity and humans in the environment and I think it's important to emphasise that there are some bright spots in that picture."

Related topics

- Published25 February 2021

- Published28 May 2021

- Published10 August 2021