Ethiopia's Tigray war: Inside Mekelle cut off from the world

- Published

These people are queuing outside a bank to try and get their money

A truce declared last week by Ethiopia to allow the delivery of aid to the northern Tigray region has offered some hope that the 17-month civil war there could be coming to an end.

The region has been totally cut off for many months, leaving millions in desperate need of food and essential supplies. A resident of Tigray's capital, Mekelle, which is under the control of the TPLF rebels, has managed to tell the BBC what life is like.

Getting hold of the basics needed to survive every day is a source of anxiety.

As a father with two small children, it breaks my heart that I am not able to provide for my family. This is in part because I am unable to use the money I have because all the banks are shut.

Many of us are facing this problem and cash is scarce.

I have not had access to my account since June last year and instead I have been borrowing money from friends and relatives here to buy food for the family.

Relatives abroad have also wanted to help but because all phones lines and the internet have both been cut off it is impossible to arrange this.

On top of this food prices have skyrocketed.

The local staple grain, teff, as well as wheat flour, pepper and cooking oil are becoming harder to afford.

A year ago, 100kg (220lbs) of teff would cost about $80 (£60) but now it will set you back $146.

Those who can afford it are buying a smaller quantity of teff and mixing it with cheaper sorghum and wheat in order to make injera (flat bread), which is an essential part of every meal.

But many others cannot buy teff at all.

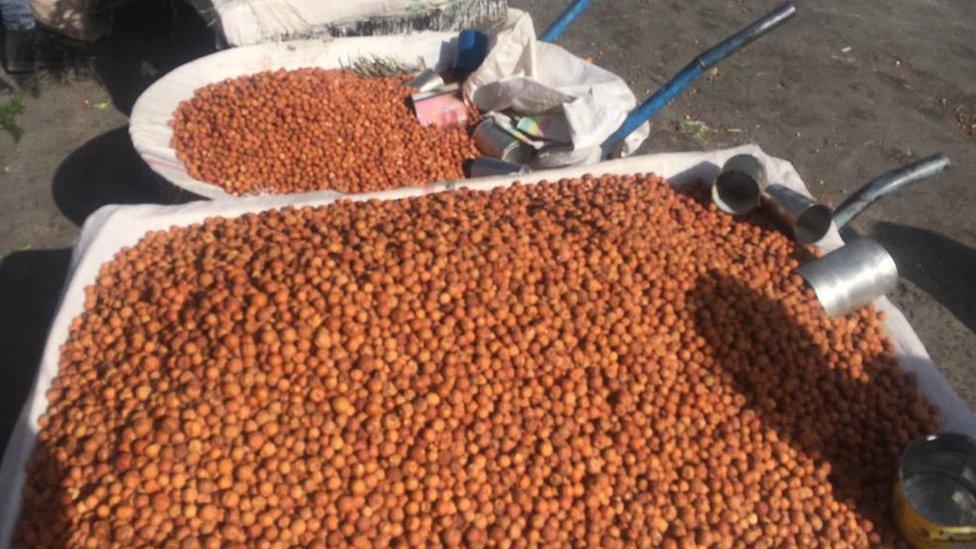

Foraged wild fruits, which people did not used to eat, are now on sale at roadside stalls

We have been told to plant vegetables in our compound and we are working on it. The problem though is that we have to get hold of water.

We used to buy a 200-litre barrel of water to get us through the week, but now we can't afford it and instead we're getting water from shallow wells.

New shoes or clothes for the children and eating meat have become luxuries.

Running water and electric power are limited and they come on and off throughout the day - sometimes days can go by without either.

Many people are out of work and the majority of shops and business centres in Mekelle are closed as they are either unable to pay rent for their shops or lack supplies to sell.

Many businesses in central Mekelle are shuttered but people are selling fruit and vegetables in front of them

As a result, people have started selling off their assets such as cars, furniture and jewellery to buy food. And they are forced to sell at a huge discount.

A 21-carat gold ring, which once cost $64 can be sold for as little as $12. A car can go for $7,000 even though it used to cost $16,000.

Once people have run out of things to sell they have turned to begging and there are so many beggars on streets - the majority are mothers with children.

Medical services have also run out of drugs.

Those with chronic health conditions are dying because of a lack of medicine.

People living with HIV are receiving their antiretroviral tablets intermittently.

Celebrations such as religious feasts and weddings that used to be such a vital part of the social fabric have become a distant memory.

As for what I do every day - before the schools re-opened I used to sleep in late.

This was because I was up at night watching and listening to all the news clips that I had managed to gather.

The latest news is hard to come by.

I don't have access to the internet. Instead, I go to road-side vendors to record video and audio clips about current events which are sold for about $0.20 each.

At other times I either read books, chat with neighbours or walk.

Unaffordable petrol

Now that my son is back at school I have done a lot of walking. My phone tells me that I normally take 9,000 to 12,000 steps in a day.

I make the 2km (1.2-mile) journey to drop him off on foot most mornings. My wife then picks him up, again on foot, at lunchtime.

I used to go by car, but it has been parked outside my home for more than 18 months because I cannot afford fuel.

You can still buy it but only on the black market. A litre of petrol now costs about $10 when, before the war, it used to cost $0.42 at a petrol station.

Taking a taxi or bejaj (three-wheeled motorised rickshaw) is also out of the question, as a single journey in a bejaj costs $2.

Horse-drawn carriages are now being used for public transport.

Horse-drawn carriages have made a come-back since the war began

More people have started to cycle but even bicycles have become more expensive.

The people here want the conflict to be resolved peacefully and were very happy when news came through of the cessation of hostilities last week.

They had been waiting to see if it was more than an empty promise and after the arrival of the first aid convoy in months on Friday, it seems as though things could be changing.

I am grateful that I am surviving and can share my story but I know there are many in a worse situation than me and some may be dying.

There is perhaps a silver lining to all this: people are still supporting each other.

"Those who eat alone, will die alone" is a saying in our Tigrinya language and people follow that.

They share what they have with others even if it means they will starve tomorrow. There is so much solidarity to surviving together.

We have not named the resident for safety reasons.