Viewpoint: The privilege of being the child of immigrants

- Published

In our series of letters from African writers, Algerian-Canadian journalist Maher Mezahi reflects on his years living in Algeria as he gets ready for a new assignment elsewhere.

Recently, I have been contemplating the privilege that I and other children of immigrants have over our parents.

I first noticed the difference when growing up in Canada and observing the gulf in comfort levels between first- and second-generation immigrants.

The elders would tip-toe on eggshells when it came to claiming their rights, as if afraid that they could be sent home at a moment's notice even after being naturalised.

They also transmitted a kind of mental burden, which was the understanding that we are somehow representative of a wider demographic and thus had a responsibility to portray a positive image.

That negative pressure of being an immigrant, though, also came with the positive benefit of often having two citizenships and two homes.

There comes a point in the life of almost every second-generation immigrant's life when the prospect of moving to the "home" country, and discovering that second home, is seriously considered.

Sociologists have named the phenomenon "reverse immigration", especially when it relates to people moving from the West to less well-off countries.

For some the move is motivated by an element of rejection in their countries of birth.

This could be on the basis of religion - in Algeria, for example, there's a large community of French-Algerian Salafist Muslims who do not feel that they could practise their faith as they would have liked to in France.

Others have cited racism and the rise of extremist right-wing movements.

No more racial profiling

For me that point came six years ago, after finishing a degree in philosophy in Canada, but instead of something pushing me away from Canada, I was rather drawn by opportunities pulling me to Algeria.

I wanted to get closer to the part of my family who I only got to see during summer vacations, I wanted to improve my Arabic and - most importantly - I wanted to pursue a career in African football journalism.

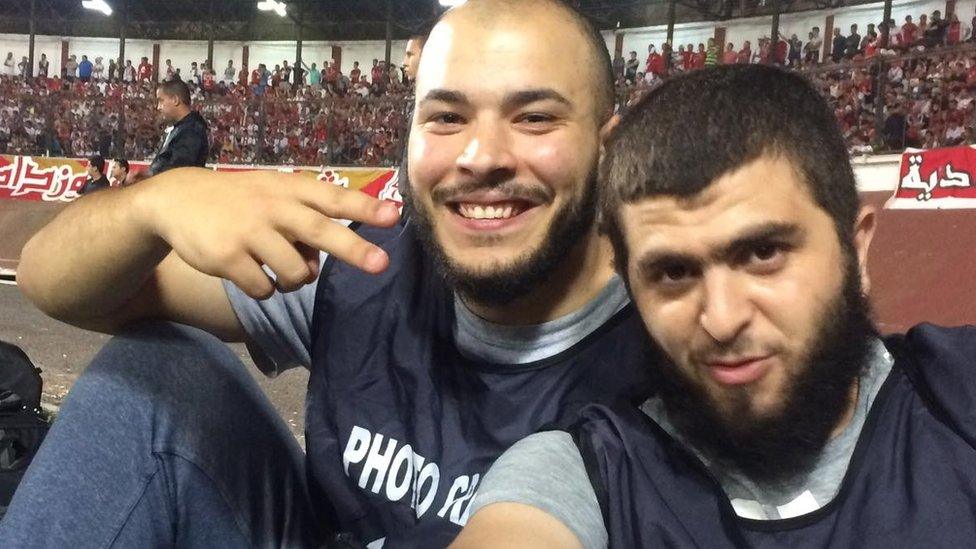

Maher (C) went to Algeria to help boost the coverage of North African football in English

To be completely honest, Canada has been good to me and my family.

Like many Muslim families, we did deal with some racism after the 9/11 attacks, but those episodes, now more than two decades ago, were isolated and did not reflect the greater good there.

However, there is something to be said for living in a place where I could feel that I was making a difference.

There are many great North African football journalists writing in Arabic and French, but not so many in English.

As a result, I felt like I was breaking new ground, or at the very least having more impact than if I did the same work in Canada.

Upon landing, I caught the first glimpse of a luxury that I possessed that my parents did not when immigrating.

For the first time in my life, I no longer belonged in the "visible minority" pool. There was no burden or fear that I would ever be racially or ethnically profiled and that was a truly liberating experience.

Higher standard of living

The second privilege was that I walked into a well-paid job at a television station with little experience, simply because I had grown up speaking English and I had studied abroad.

At the time there was a lot of good energy in Algiers.

Several dozen highly qualified Algerians from the diaspora who were around my age also wanted to try living in Algeria and developing their respected fields.

And it was not as if our standards of living dropped dramatically.

The reality is that if you make a decent salary then living in some African countries is better than living anywhere else.

You really can't beat the weather, cost of living and easy-rolling pace of life.

After seven years of being 'back home' I am now exercising another privilege: leaving"

It is undeniable, however, that a certain lustre has gone from this side of the Mediterranean over the past few years.

The Covid-19 pandemic cut Algeria off from the world and the subsequent economic difficulties spared no-one.

To make matters worse, the repression from the fallout of the 2019 anti-government protests left little room to express frustration in public forums.

So after seven years of being "back home" I am now exercising another privilege: leaving.

Being able to pack up and depart the motherland does engender guilt.

Sometimes I ask myself: "What gives you the right to come and go as you please?"

Of all the inequalities that I have witnessed here, none has been starker than those that come as a result of differences in where people were born.

A month ago, I was at a roundtable with a well-known Algerian author and a foreign journalist.

The latter asked the former why he did not want to live in Europe.

"When you have the freedom to come and go, it is not so tempting," he replied.

"You see this Mediterranean Sea?" he continued, pointing to the bay in Oran.

"To a tourist, it is a relaxing sight for sore eyes. But for a young, unemployed man with no prospects in life, it is the embodiment of oppression."

Yes, psychologically, I have personally felt more liberated here but I have also learnt about the privilege of having multiple places I can call home and the consequences for those who cannot.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external