Philly Lutaaya: The Ugandan singer who led the fight against HIV prejudice

- Published

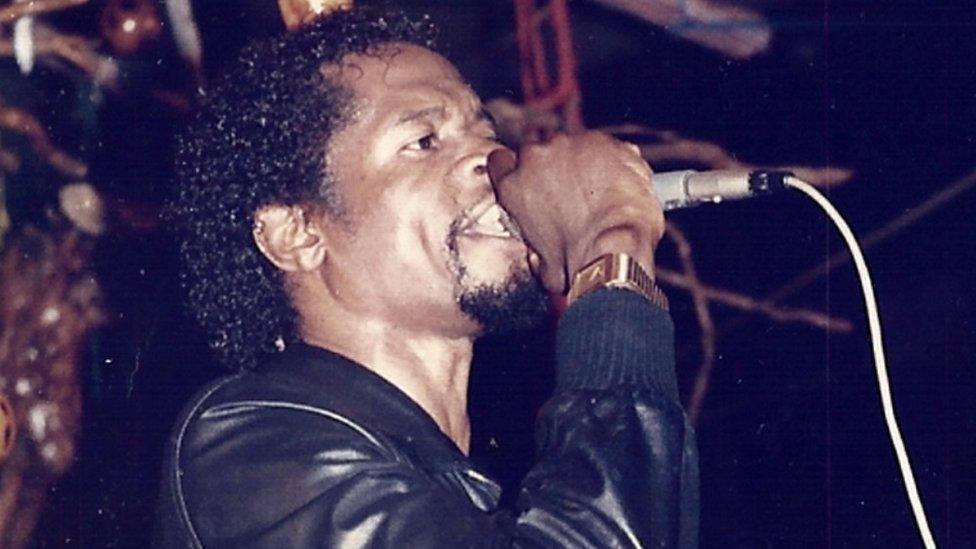

Ugandan music star, the late Philly Lutaaya, captivated fans with his music that blended reggae and African pop.

At the height of his career in 1989, he was diagnosed with HIV. Amid a climate of fear and prejudice, spawned by little knowledge of the new disease, he became the first high profile Ugandan to go public with his diagnosis.

His decision won him plaudits the world over, but the single father - who died aged 38 - unintentionally exposed his young children to stigma and discrimination.

His daughter Tezra spoke to BBC Outlook's Emily Webb about it.

I was 12 when my dad was told he had HIV, he was shocked and went into self-destruct mode. He would drink, have fun with friends and try to do everything to excess.

Eventually, he sobered up. I think he thought about his young children and decided to change.

My dad, who had separated from my mum, had taken us - his three children - to Sweden after the end of Uganda's 1980-1986 civil war. He continued his music career in Uganda but also did odd jobs so he could earn enough money to look after us.

One evening we were in the living room, and he had just bought new CDs.

We were listening to Phil Collins' I Can Feel It in the Air. Dad loved the drumming in that song; that is why I can never forget it. Being a drummer himself, it was his favourite song.

'Are you going to die?'

He surprisingly turned the music off and said: "I need to talk to you." He told us he had been diagnosed with HIV. We didn't understand.

"Are you going to die? But there is nothing wrong with you," we said.

I remember my big sister cried; my little brother didn't register anything. And me, being the tough one, I said: "You're going to die? What does dying even mean?" I could not digest the news.

When he tried to talk to his family about going public, his brother strongly opposed it because of how horribly HIV patients were being treated.

People were literally being locked up and secluded from their families. Most were being taken to their villages to die.

"Look, if you don't do this with me, I will have to do it on my own," he told his brother.

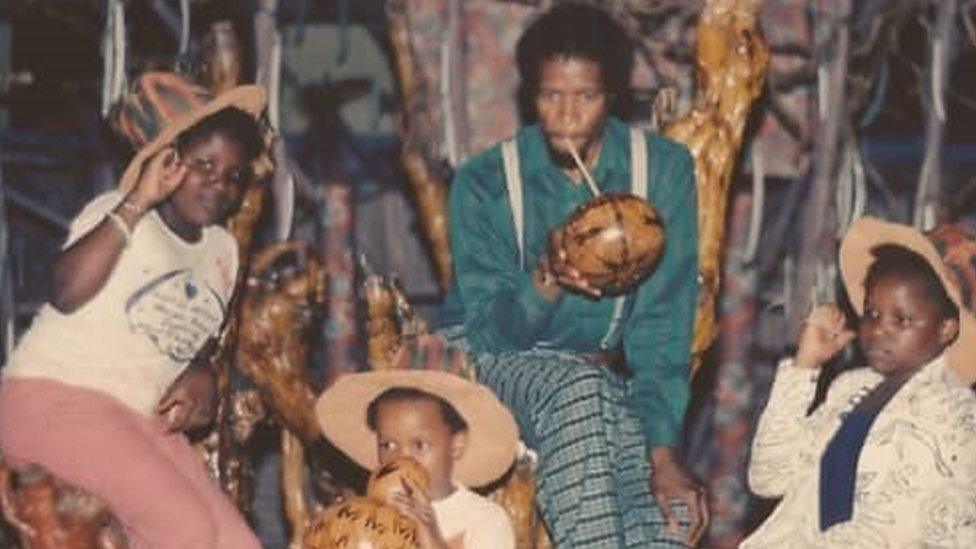

The singer is seen with his children: (left to right) Jastin, Lennon and Tezra

Eventually, my uncle got on board, and dad came out with his diagnosis at a press conference in Uganda's capital, Kampala.

At first, people did not believe him because he did not look sick at all.

He had just released a successful album, Born in Africa. They thought Western public relations companies were behind the announcement to sell more music.

"I wanted to go on shouting loud about this crisis. I ignored people who were calling me a liar, people who were calling me an opportunist. I knew the time would come when they would understand," my dad said.

At this time, we were being sent off to live with foster families in Sweden because he was a single parent who was in and out of hospital. We took it as an adventure, not knowing the underlying reason.

'Stand up and fight'

When he recovered a bit, he left us in Sweden and returned to Uganda and launched the Alone and Frightened album. This addressed the HIV stigma head on.

"We've got to stand up and fight. We'll shed a light in the fight against Aids. Let's come on out," he sang on the title track.

Soon after the release of the album, doctors asked him to return to Sweden for further treatment, which he did.

But as he noticed that his life was slipping away, he asked to be flown back to Uganda.

We were all flown there with him. He was too weak to walk and when he got out of the plane he was put on a stretcher and taken straight to the hospital where he would spend the last two weeks of his life.

These were the longest two weeks I think that I have ever experienced.

On 15 December 1989, we lost him.

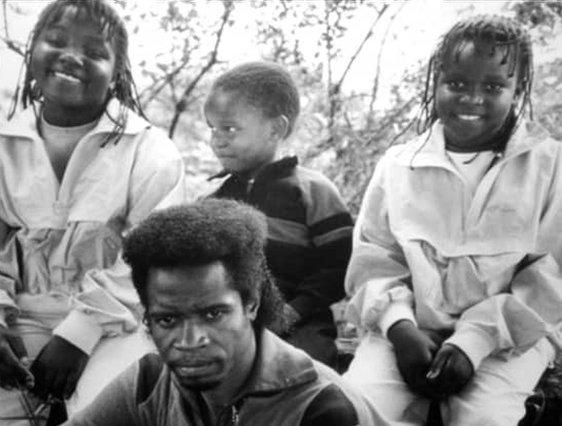

Tezra and her siblings are keeping alive the legacy of their father

Wherever we went, people knew that we were the children of the late Philly Lutaaya.

I was kind of sickly when we returned to Uganda. Because of this, some people would say that maybe I had contracted HIV from my father.

We did feel the stigma even before he died. In Sweden, most of his friends had stopped inviting us to their homes. They would not want us to play with their children.

Five years later, when I returned to Sweden, I didn't introduce myself as Tezra Lutaaya.

Ten years of healing

I distanced myself from the name just to heal. I was angry with him during that time because he had exposed us to this. I was not even thinking about the illness he had.

It took me about 10 years to come to terms with his death, to mourn and understand that this was not all about me; it was something more significant.

This moment came when I was at university in the US. I came across a documentary with a familiar name - Born in Africa, which chronicled the final tour of awareness my dad did few months before his death in Uganda .

I hadn't watched the documentary. I remember it came out just after my father's death and I couldn't deal with it at the time.

Ten years later, I was able to watch the documentary, it re-opened my box of memories.

I could now really understand his journey and what he had been fighting for. I decided to do something and started a charity, Philly Lutaaya Cares.

The lives of Tezra (R), Lennon (C) and Jastin (L) were turned upside when their dad got HIV

There is more awareness and less stigma now, but I continue my father's legacy by empowering young people with skills, financial literacy and reproductive health education. This should help as poverty is one of drivers of HIV infections.

Whenever I come across something challenging, I say to myself: "Come on now; nothing is compared to what the big man did. So please, you have to be brave as your father once was."

Philly Lutaaya's legacy doesn't just relate to the incredible work he did around HIV and Aids; his Christmas songs still mark the start of Christmas.

Rather than make me sad as they used to, my dad wanted people to listen to his music; whenever Christmas comes, I am happy to put on his album and play it for my children and tell them: "That is grandpapa singing."

It's such a joy.

The interview was produced and edited by Eric Mugaju. You can listen to it here.