Why ex-French colonies are joining the Commonwealth

- Published

As two former French colonies in Africa join the Commonwealth, regional analyst Paul Melly considers the allure of the English-speaking club.

Gabon and Togo have moved to strengthen their diplomatic armoury in a bid to ease their reliance on France.

They have been admitted to what was originally founded as a club of former British colonies but has been steadily diversifying its composition. These two small francophone African nations are now the Commonwealth's 55th and 56th members.

Rwanda joined in 2009 and Mozambique came into the group in 1995. None of these states had particular past historical ties to the UK.

The fact that they have opted to join the Commonwealth suggests that they see the organisation as a useful network of diplomatic and cultural influence, and for exercising "soft power" on the world stage.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson was in Rwanda for three days for the recent Commonwealth summit

It also testifies to the importance of English as a language of business, science and international politics and the necessity of building a range of connections to support economic development and get diplomatic messages heard.

For Gabon and Togo, Rwanda offers an encouraging precedent: just 13 years after joining, it has now hosted the organisation's summit meeting, attended by heads of state and government from all over the world, though there were some notable absentees, including South Africa's President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Youth appeal

Gabon and Togo's entry to the Commonwealth also comes at a time when the relationship between Africa and France has become so contentious.

A growing number of younger urban citizens demand an end to the CFA franc currency which is pegged to the euro under an arrangement guaranteed by the government in Paris. The French military presence in the Sahel is also controversial.

So joining the world's largest anglophone bloc is likely be popular among many young Togolese and Gabonese.

That helps to modernise the image of two regimes that were for many years perceived as particularly emblematic of the traditionally close relationships between leaders in Africa and in France - "la françafrique".

There was a time when such a development would have provoked angst among Paris policymakers fearing an erosion of influence south of the Sahara. But today's French governments take a much more relaxed view of such trends.

For the same arguments about diversifying contacts and building up new vehicles of international connection have also fuelled the steady expansion of the Commonwealth's francophone sister, the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF).

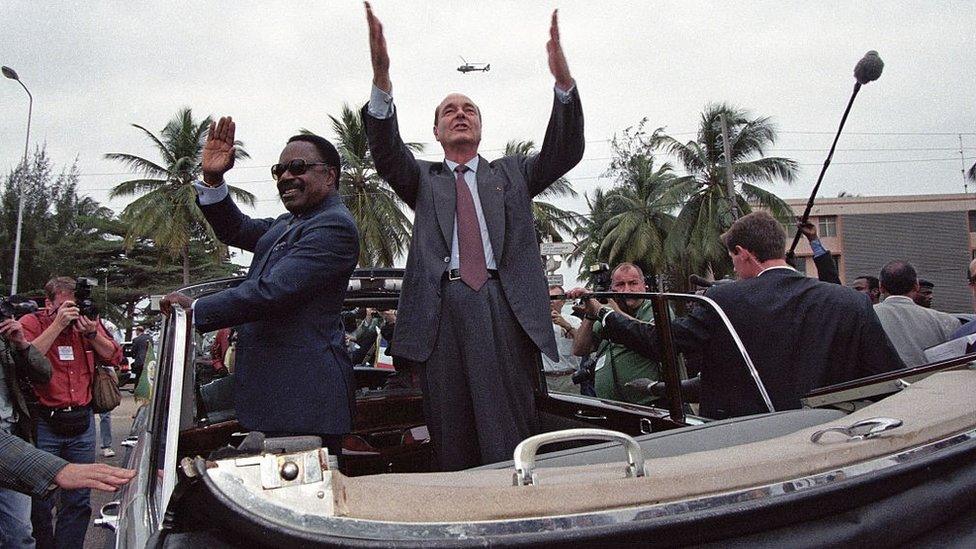

The late presidents of Gabon and France, Omar Bongo (L) and Jacques Chirac (R)

It actually claims 88 member states and governments - including Rwanda, whose former Foreign Minister Louis Mushikiwabo is its secretary general. Its regional offices for West and central Africa are in fact hosted by Togo and Gabon, and it too is growing.

In March Ghana's Foreign Minister Shirley Ayorkor Botchwey announced that her country, a former British colony which has been an associate member of the OIF since 2006, would complete the transition to full membership of the organisation.

Ghana, with strong democratic institutions and a dynamic economy, will be one of a growing number of countries that are full and active members of both the Commonwealth and the Francophonie - for solid diplomatic and practical reasons.

Most of its neighbours in West Africa are French-speaking and the government has been taking steps to equip its young people to make the most of this economic, cultural and political reality - for example, there are now 50 bilingual schools.

Nor should one forget the significant development of the small but still influential Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP) - most of whose members are African.

Democracy tests

But all three groupings - the CPLP, the Francophonie and the Commonwealth - face the delicate challenge of how to promote good governance, democracy and human rights - an issue with which the African Union and some of the continent's regional blocs, notably the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas), are also wrestling.

Both the Commonwealth and the OIF send experts to help member states improve their electoral systems, but when it comes to membership conditions they tend to opt for inclusion and gentle encouragement rather than the assertion of a strict line.

Togo has previously been hit by protests to demand political reform

Togo was ruled by the notoriously brutal dictator President Gnassingbé Eyadéma from 1967 to 2005, and has since then been led by his son, Faure Gnassingbé.

Gabon's President, Ali Ben Bongo Ondimba, is the son of Omar Bongo, head of state from 1967 to 2009, who swam with the trend towards multi-party politics in the 1990s but took care to maintain the predominance of his ruling party and the role of his family in government. Before succeeding to the presidency, Ali Bongo was defence minister.

The Commonwealth's official press release announcing the admission of Togo and Gabon stated: "The eligibility criteria for Commonwealth membership, amongst other things, state that an applicant country should demonstrate commitment to democracy and democratic processes, including free and fair elections and representative legislatures."

Yet Rwanda's President Paul Kagame, although lauded for overseeing undoubted social and economic development progress, is accused by rights groups of being uncompromisingly authoritarian in the exercise of power. Critics say the opposition is cowed and marginalised.

Mr Kagame claims his government upholds human rights, and there is "nobody in Rwanda who is in prison that should not be there".

Gabon will face a key barometer of governance with next year's presidential elections. But for Togo, there is a fairly immediate test.

The very day of the Commonwealth announcement, the authorities banned a planned demonstration by the opposition Dynamique Monseigneur Kpodzro (DMK) movement to protest against the rising cost of living, and what it called bad governance and injustice.

The DMK has rescheduled the protest for 16 July. It will be interesting to see whether Togo's new status as a Commonwealth member prods the government into taking a more lenient line.

Paul Melly is a consulting fellow with the Africa Programme at Chatham House in London.

You may also be interested in: