Queen Elizabeth's death stirs South Africa's colonial memories

- Published

The Queen visited a racially segregated South Africa when she was 21 with her father King George VI

Over the past week South Africa - a country with a unique and complex relationship with the British Crown - has reacted in a conspicuously muted fashion to the death of Queen Elizabeth. While some here are quietly mourning her and remembering, in particular, her unique friendship with Nelson Mandela, many others have chosen to focus, if at all, on the bitterly contested and enduring legacy of Britain's empire.

"I wouldn't say I don't like the Queen - no, no, no. But my everyday reality is [affected] by the impact of colonisation," said Sibulele Steerman, a university student, standing beside an open sewer in an impoverished township outside Cape Town.

These days, many younger South Africans, in particular, are questioning the compromises that accompanied their country's transition to democracy in the early 1990s, and are demanding that Western nations do far more to acknowledge centuries of colonial exploitation.

"My grandmother liked the Queen. But we're a different generation," said Ms Steerman, noting this week's calls, on social media here, for Britain to return what they say are the "stolen" South African diamonds that feature in the Crown Jewels. The Cullinan diamond, the largest ever found, was given to King Edward VII on his 66th birthday by colonial officials.

It was soon after World War Two, that Queen Elizabeth - then a Princess - first visited the southern tip of Britain's vast African empire, arriving in Cape Town with her family on a converted warship in 1947. At the time, South Africa, while independent, still had the British King, George VI as its head of state.

Black and white newsreel footage showed Elizabeth, and her sister Margaret, laughing and playing tag, in a holiday mood, with sailors on the deck of HMS Vanguard in the shadow of Table Mountain.

But as the royal party came ashore, their focus turned to the urgent task of trying to help Britain maintain its global influence and trading links, at a time when many countries were shaking off the shackles of empire in the aftermath of the war.

While in Cape Town, Princess Elizabeth turned 21, and marked the moment with an earnest speech about her future role as Queen.

"I declare before you all that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong," the Princess declared, in an address broadcast around the world.

Hours later, the elites of the port city - almost exclusively white - gathered in their finery for a royal birthday party. Also in attendance that night was one black man - rising ballet star Johaar Mosaval.

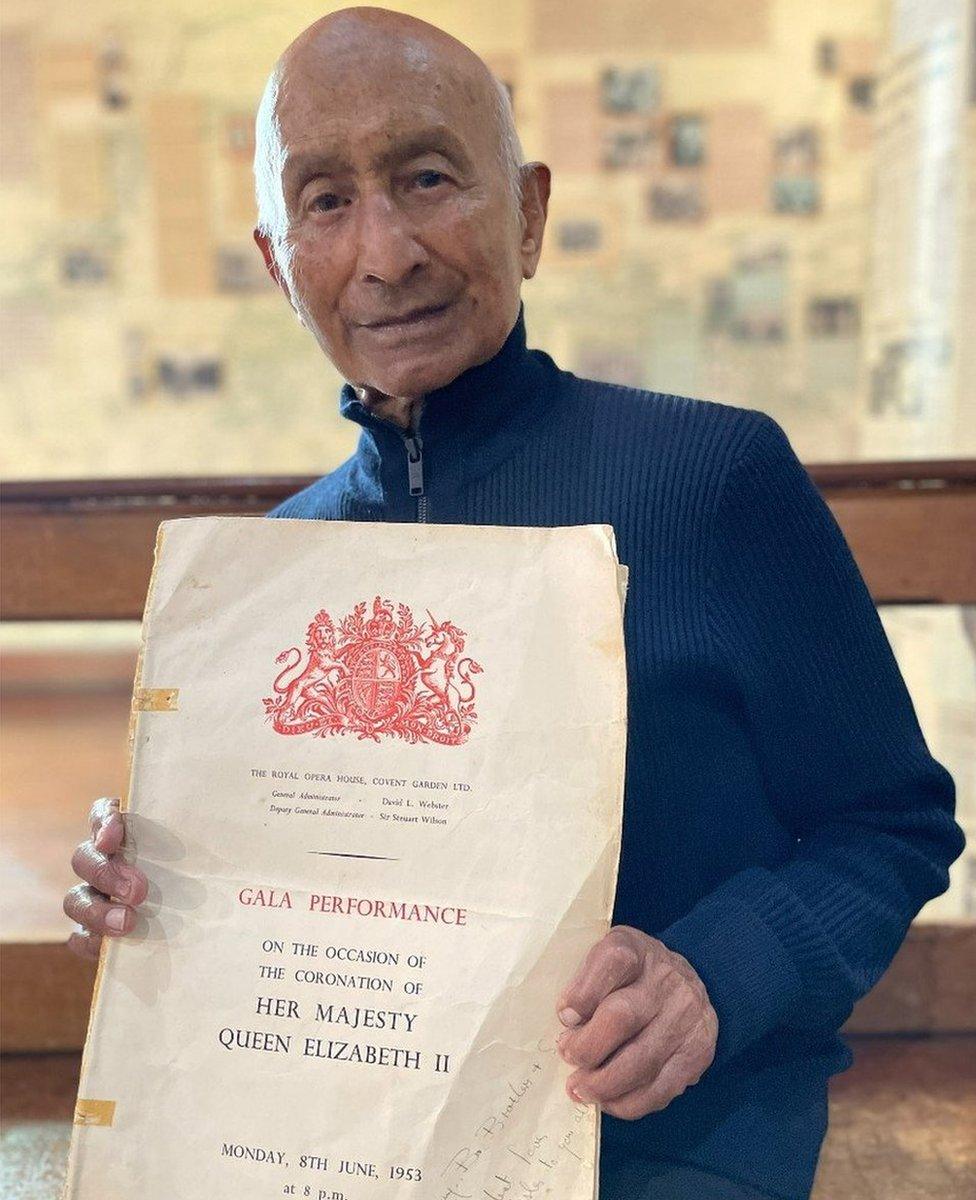

"I felt absolutely enraptured. Honoured. Overwhelmed. I felt this is remarkable to see her on her 21st birthday," Mr Mosaval, now a frail but elegant 94-year-old, recalled this week in Cape Town.

A few years later, he was selected to dance at Queen Elizabeth's coronation in London.

"I was the first black in the world to join the Royal Ballet. I still have the programme of the coronation as proof that I danced a solo for her Majesty," he said proudly, going on to praise the Queen for "the very great part she has played all over the world".

Mr Mosaval holds up the programme for the exclusive gala

The 1947 royal tour of southern Africa - conducted mostly by train - was hailed as a great success.

"These events in South Africa are being watched by the whole world. They will silence many voices which have been all too ready to say that the days of the British empire are over," declared a British newsreader at the time.

But in truth, Britain's empire was already crumbling.

In South Africa's case, a racist white-minority government came to power, promoting a brutal policy of racial segregation known as apartheid, which devastated the lives of the black majority and led to the country leaving the Commonwealth - a loose network of former British colonies - and facing decades of international isolation.

It took half a century before Queen Elizabeth was able to return to South Africa, the country having rejoined the Commonwealth. In 1995 she stepped ashore once again in Cape Town to be welcomed by the newly elected President Nelson Mandela - who'd only recently been released from years in prison in order to oversee a turbulent but ultimately successful transition from apartheid to democracy.

The Queen struck a close relationship with Nelson Mandela

"It was a very unusual relationship," Mandela's private secretary, Zelda La Grange said this week, remembering the bond which the two equally regal figures quickly developed.

"On one occasion he visited her at Buckingham Palace… and said: 'Elizabeth, you've lost weight.' And, of course, the Queen burst out laughing. And afterwards Mr Mandela's wife said: 'You can't call her Elizabeth, she's the Queen of England.' And he said: 'Why not? She calls me Nelson."

But did that close relationship come at a cost? Some believe it contributed to Mandela's ANC-led government's reluctance to confront Britain directly over the issue of reparations - financial compensation for the damage wrought to South Africa's economy and society by centuries of exploitation and colonisation.

"I don't believe that President Mandela raised the issue," said Mamphela Ramphele, a prominent anti-apartheid activist and politician.

"The Queen as an individual probably cared. But the fact is that [she was] a symbol, and the head of the British [state], and there weren't really any steps taken to acknowledge, let alone to… undo the structural inequalities that were built into a racist, exploitative South Africa, both during the colonial period, under apartheid, and even post-apartheid."

She noted, pointedly, that the Commonwealth might have plenty in common, but the wealth was all kept in London.

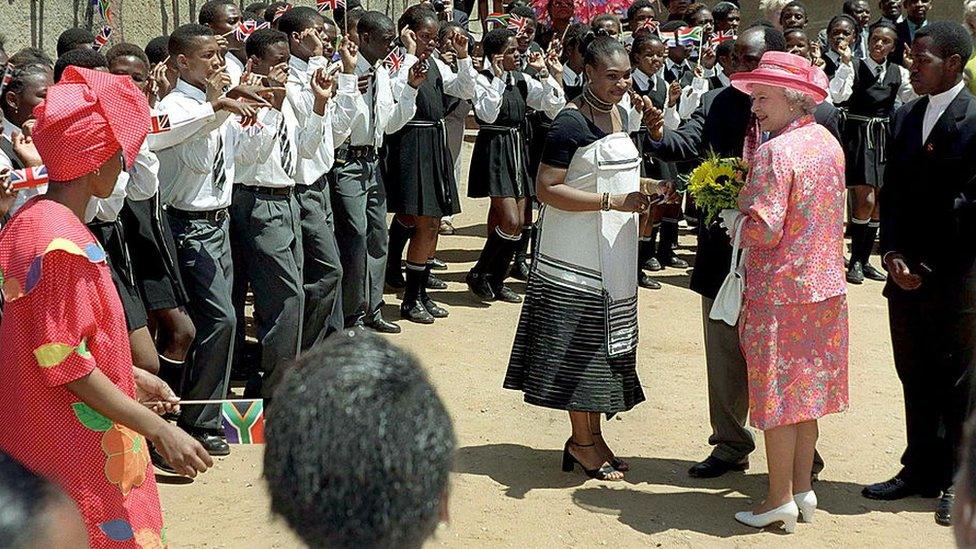

But the Queen's 1995 visit to Cape Town was, nonetheless, a powerful symbol of post-apartheid South Africa's return to the international fold, and the end of its pariah status. Despite security concerns, the Queen insisted on seeing the reality of the new South Africa, visiting several violence-plagued townships.

The Queen during her visit to the Education Centre in Alexandra township in Johannesburg in 1999

"It was a big thing. People were curious to see her. There were about 10,000 people here, and it was nearly chaotic. But it mattered that she came to the black township. She could have stayed in the city, and she was not scared, not scared," said Ezra Cagwe, a retired sports coach who attended one overcrowded royal event in Langa township.

"It's not like people are so sad here today. [The visit] was a long time ago, and she was old, as well," said Mr Cagwe.

"I don't think there's any connection at all between Britain and South Africa," said a woman, hanging out washing outside her makeshift shack.

"Nothing is getting better here. There's more violence, more crime, more poverty," said one of three schoolgirls, walking past and admitting they knew and cared very little about the British Royal Family.

But older South Africans are more likely to remember, favourably, the educational opportunities afforded to them during the days of empire - in sharp contrast to the degrading treatment and racist "bantu education" which black people experienced during apartheid.

There are still many white South Africans in Cape Town who hold British passports and who've mourned the Queen's death - although the televisions in the bar of the exclusive Kelvin Grove Club were resolutely switched to rugby and cricket on a recent visit.

"I think [the Queen] has been a great supporter of South Africa. Colonialism is a dirty word in this country, but I'm a supporter of colonialism and I think there were many good aspects… which probably outweighed the bad things," said Craig Strang, sitting with friends before a log fire.

But the national mood - if callers to prominent radio stations can be seen as a reliable indicator - has tended to shun royal nostalgia, and to focus, instead, on the issue of colonisation.

That may not be surprising, in a country bitterly divided over why, almost three decades since the end of apartheid, so many South Africans are still struggling to overcome inequality and entrenched poverty.

"Most South Africans are saying: 'Give us an opportunity to be frank in our assessment of [the Queen's] legacy.' This is the person we look at and think: 'Ha - that's the face of the British colonial empire, an institution that enriched itself through violence, through theft, through oppression," said Clement Manyatela, who presents a popular morning show on Radio 702.