Gambia cough syrup scandal: Mothers demand justice

- Published

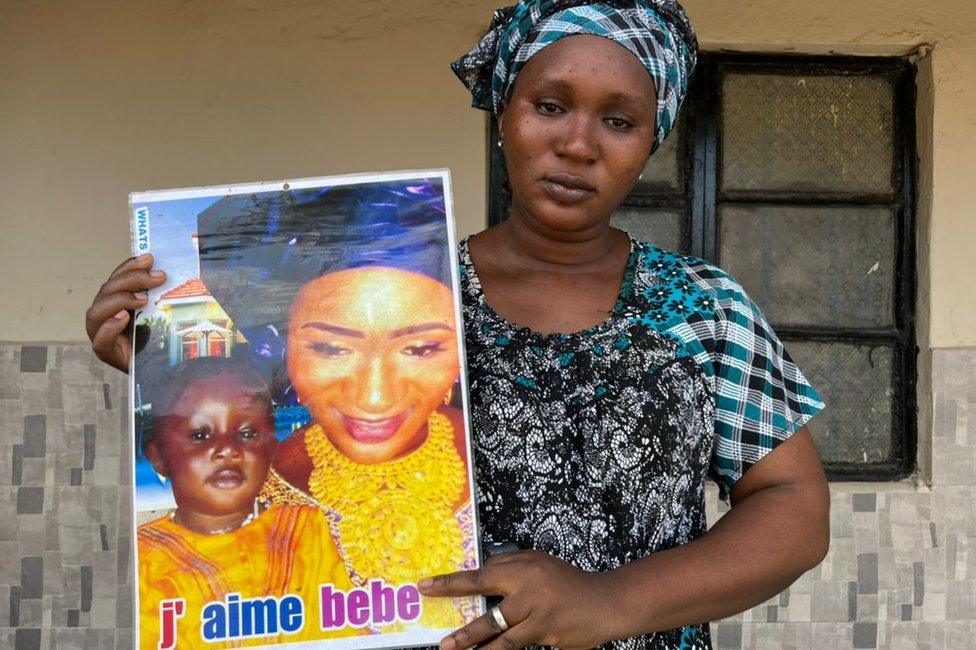

Mariam Kuyateh says she wants justice for her son Musa

A red toy motorbike sits in the corner of Mariam Kuyateh's home gathering dust.

It was meant for her 20-month-old son, Musa, but he passed away in September.

He is one of the 66 children in The Gambia who are thought to have died after being given a cough syrup that had been "potentially linked with acute kidney injuries", according to the World Health Organization.

No-one in the family touches Musa's toy - a reminder of what has been lost.

His 30-year-old mother, who has four other children, was in tears remembering what had happened to her son.

Sitting in her home in a suburb of The Gambia's largest city, Serrekunda, she explained that his sickness started as a flu. After he was seen by a doctor, her husband bought a syrup to treat the problem.

"When we gave him the syrup, the flu stopped, but it led to another problem," Ms Kuyateh said.

"My son was not passing urine."

She returned to the hospital and Musa was sent for a blood test, which ruled out malaria. He was given another treatment, which did not work, and then a catheter was fitted, but he did not pass urine.

Finally, the small child was operated on. There was no improvement.

"He couldn't make it, he died."

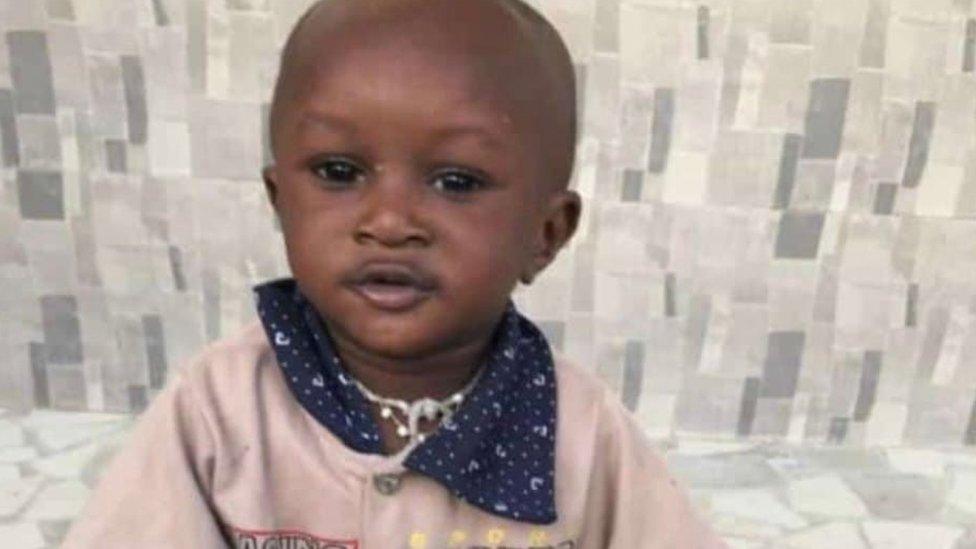

Musa was one of the 66 children who died after taken the cough syrup

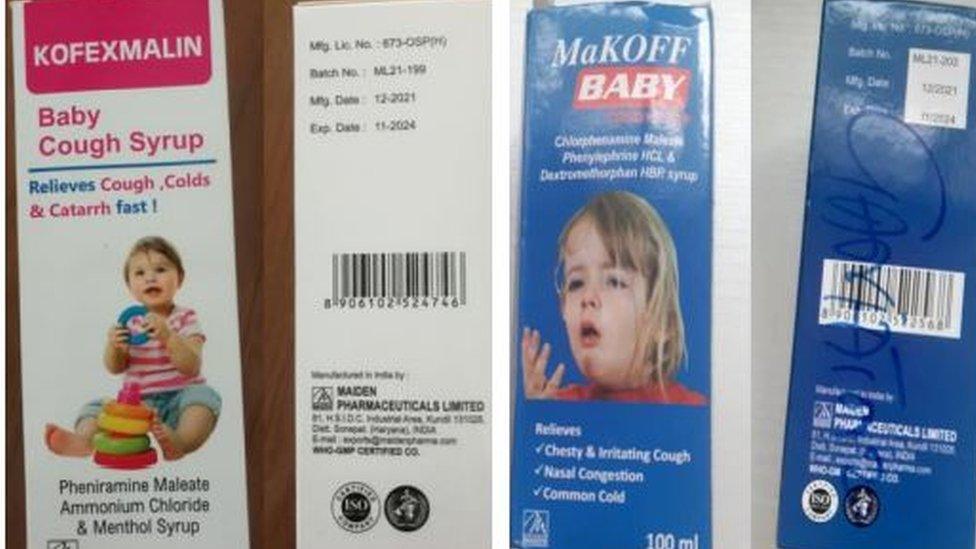

Earlier this week, the WHO issued a global alert over four cough syrups in connection with the deaths in The Gambia.

The products - Promethazine Oral Solution, Kofexmalin Baby Cough Syrup, Makoff Baby Cough Syrup and Magrip N Cold Syrup - were manufactured by an Indian company, Maiden Pharmaceuticals, which had failed to provide guarantees about their safety, the WHO said.

The Indian government is investigating the situation. The firm has not responded to a BBC request for comment.

There is a lot of anger in The Gambia over what has happened.

There are growing calls for the resignation of Health Minister Dr Ahmadou Lamin Samateh, along with the prosecution of the importers of the drugs into the country.

"Sixty-six is a huge number. So we need justice, because the victims were innocent children," Ms Kuyateh said.

Mariam Sisawo had to take her daughter to hospital three times before she was referred to a hospital in the capital

Five-month-old Aisha was another victim.

Her mother, Mariam Sisawo, realised one morning that after having taken the cough syrup, her baby was not passing urine.

On an initial visit to the hospital, the 28-year-old was told that there was nothing wrong with her daughter's bladder. It took two more trips there on consecutive days before Aisha was referred to a hospital in the capital, Banjul, which was 36km (22 miles) away from their home in Brikama.

But after five days of treatment there, she died.

"My daughter had a painful death. At a certain time when the doctors wanted to fix a drip on her, they could not see her veins. Myself and two other women in the same ward, we all lost our children.

"I have two sons and Aisha was the only girl. My husband was very happy to have Aisha and he still can't come to terms with her death."

The Gambia does not currently have a laboratory capable of testing whether medicines are safe and so they have to be sent abroad for checking, Gambia health services director Mustapha Bittay told the BBC's Focus on Africa programme.

On Friday, President Adama Barrow said the country planned to open such a laboratory. In a televised address to the nation, he also directed the health ministry to review relevant laws and guidelines for imported drugs.

Ms Sisawo believes the government should have been more vigilant.

"This is a lesson for parents, but the greater responsibility is with the government. Before any drugs get in to the country, they should be properly checked if they are fit for human consumption or not," she said.

Alieu Kijera took his son, Muhammed, to neighbouring Senegal for treatment but the doctors were unable to save him

Isatou Cham was too distressed to talk about the death of her two-year-and-five-month-old son, Muhammed.

She left the living room of their home in Serrekunda crying with her two other children.

Muhammed's father, Alieu Kijera, explained what had happened to his little boy.

He said he was taken to hospital when he had a fever and was unable to pass urine. But the doctors were treating Muhammed for malaria and his condition was getting worse.

The medics then said he should be treated in neighbouring Senegal, where the health service is thought to be better, but while there was some improvement, it still did not save him.

Mr Kijera is angry that his country does not have a good enough health system and he was forced to travel abroad.

"If there was equipment and the right medicine, then my son and many other children could have been saved," he said.

Related topics

- Published6 October 2022

- Published7 October 2022