Seychelles: The island paradise held prisoner by heroin

- Published

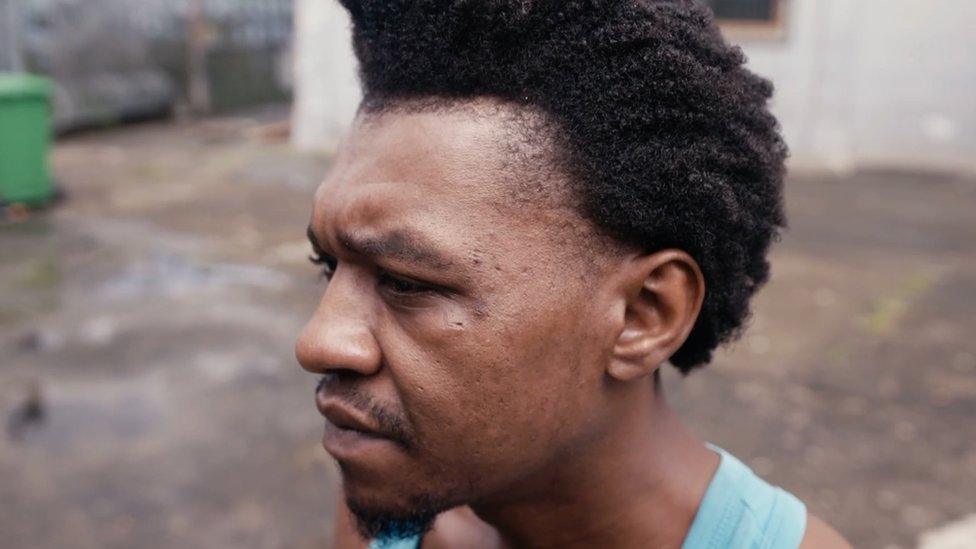

Jude Jean has been in and out of jail after stealing in order to get money to buy heroin

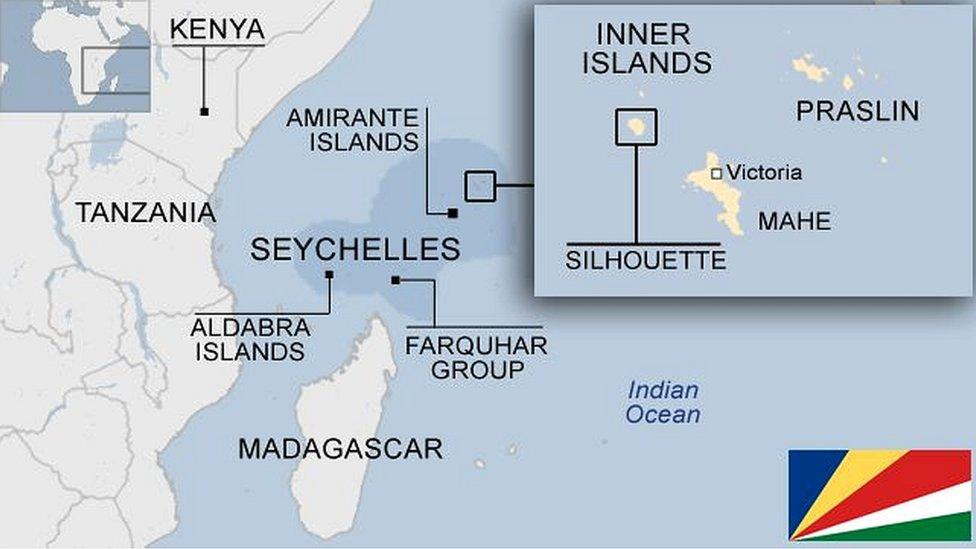

Some 10% of the local population in the tropical island nation of Seychelles is dependent on heroin in what is now an epidemic, according to the country's government. Even being locked away offers no protection for those dependent on the drug. BBC Africa Eye gained rare access to the main jail to witness the sharp end of a problem threatening to overwhelm the country.

Nestled on the top of a hill, surrounded by beautiful views of the Indian ocean is Montagne Posée Prison, Seychelles' main correctional facility.

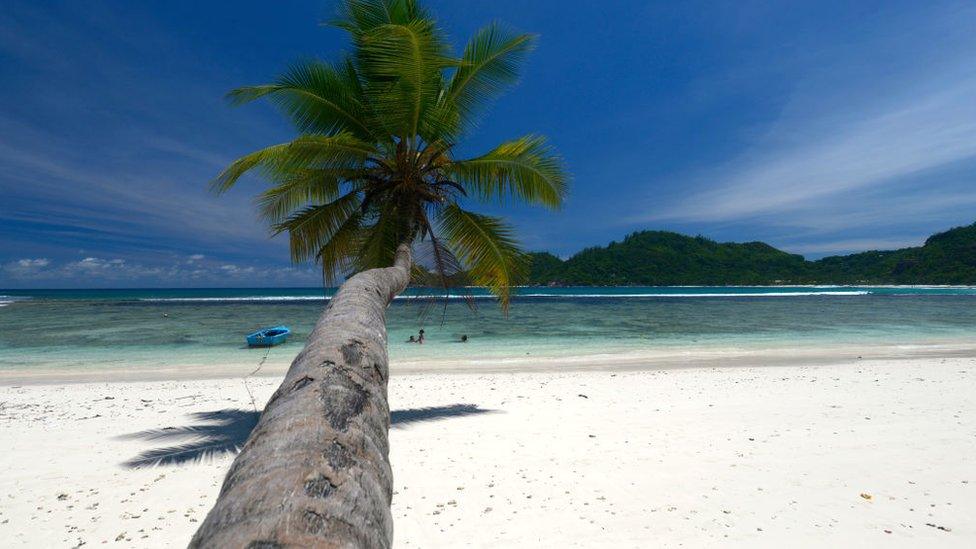

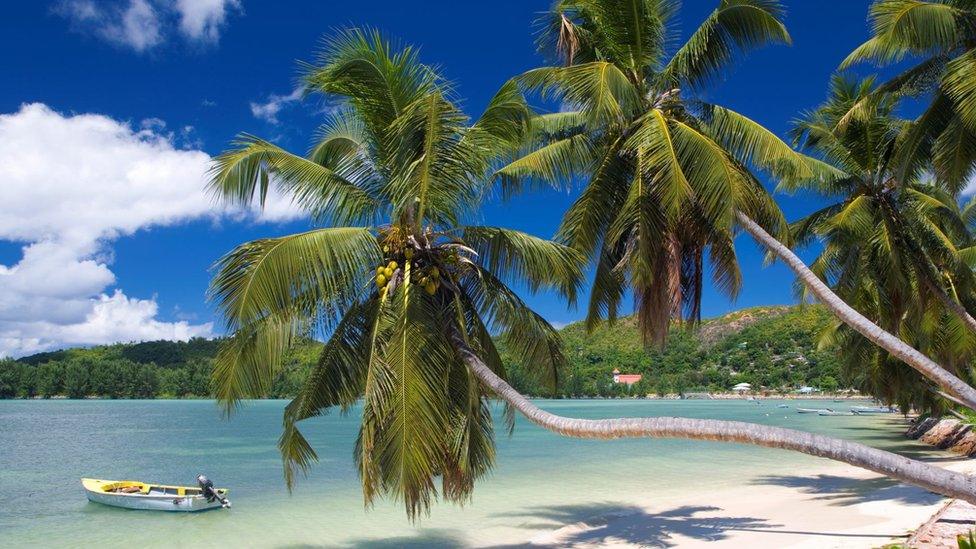

Seychelles is a country of contradictions, but still, it is hard to reconcile these breath-taking vistas with what lies within.

At the entrance to the place where the prisoners are kept, after going through numerous locked gates and passing miles of coiled barbed wire, there is a four-metre-high mural of Nelson Mandela, painted on the office block wall.

Beside the smiling face of the late South African president - who was of course a prisoner himself - there is a quote which reads: "It is said that no one knows a nation until one has been inside its jails."

And it is true that in many ways this prison is a reflection of what is going on in Seychelles beyond its luxury five-star branding.

We are here to meet one of the inmates, Jude Jean, but the BBC team is first taken to what the prisoners tell us is a bit of a show cell for visitors. It is clean but cramped.

There are eight beds, four on each side - one atop the other without space to sit up straight. In the same room there is a toilet and shower - privacy is not a thing.

Nearby are the dirty and dilapidated kitchens. Rotting fish guts clog the drain, the stench is overpowering but the flies are enjoying the feast.

Then there is the main cellblock. The darkness is overwhelming. It is early afternoon yet there is no daylight, small bulbs in a nearby corridor cast a weak light. The prisoners use cardboard boxes to create privacy behind the bars of their open-fronted cells. Some of them are so small they look more like cages and there are dirty mattresses on the floor.

The prison conditions are cramped and afford little privacy

The heroin problem also lurks in the darkness as class A narcotics flow through these cells.

Prison offers no protection from what is happening outside.

Seychelles is facing what is now an epidemic.

It is estimated that around 10% of the Seychellois population is hooked on heroin. So much so that foreign workers are having to be brought in to do the work that drug-dependent locals cannot.

In the jail, Tanzanian guards are rotated onto the staff in an attempt to stem corruption and the flow of heroin into the cells - but it is not working.

Corruption, drugs and prison

Even President Wavel Ramkalawan admits the prison is not fit for purpose.

"When you have such a mess, this is the breeding ground for corruption on the part of the officers. And once you have corruption, then drugs will continue to enter prison," he tells the BBC from State House in the capital, Victoria, adding that he is planning to build a new jail.

He acknowledges that "the drug situation is very bad".

"At this point in time, per capita, as far as consumption of heroin is concerned, Seychelles is number one in the world. And this is not a statistic that gives me personally great pleasure."

It is visitors' day in the prison and Jude, who is on remand for theft, is waiting for his mother.

The family room is outside - it's a concrete courtyard surrounded by wire-mesh fencing with plastic furniture.

Jude is likable - warm and friendly, confident but humble. He is also dependent on drugs.

"I'm ashamed to say but you know, I'm an addict," he tells us, "and it's not easy."

Today as he takes his seat, his eyelids seem too heavy for him. Despite being in prison, he has managed to get his heroin fix that morning, as well as a few spliffs.

Jude's mother, Ravinia, has stuck by her son despite his drug dependency having an impact on her

Jude has been in and out of prison for more than a decade, mostly for theft to feed his habit.

His mother Ravinia has had to cope with this, as well as another terrible tragedy.

She is a bubbly woman; her smile lights up the room and her laugh is larger than life.

She worked hard for years running a fast-food outlet, trying to provide for her four children and give them a good life.

But heroin took all of that away.

In 2011 Ravinia's eldest son Tony was found hanged. His death remains a mystery, but Tony was heavily involved in heroin, and she has no doubt the two are linked. She does not believe he took his own life.

As she speaks, she looks a million miles away, pain and confusion etched across her face.

'Be strong, mum'

To this day she is baffled as to how not one but two of her sons went down this path.

"Even if you tell me not to blame myself, I have to blame myself," she says. And so many mothers across the country feel the same.

When Ravinia sees Jude, her mood and smile brighten.

"I'm happy to see you my son," she says as she hugs him tightly.

"I'm happy to see you too Mum," Jude beams back.

As they sit down she tells us: "You know we talk, even though I know he lies to me sometimes, we talk, we are friends!"

But the strain soon shows. As she breaks down in tears, Jude wipes away his own, and tells her: "Be strong mum, be strong."

And she is.

She is Jude's rock and you can see how much it means to him, but over the years he has tested her.

"We don't have any of the anything nowadays because it's all gone. He even took my chequebook and started [writing] cheques," she explains.

"He took everything… I remember once we didn't even have bed sheets. Everything he saw, he just took it and sold it for drugs."

The first time Jude went to prison Ravinia was relieved, but her respite was short-lived, she says it is as if she had sent him to "a school for criminals".

Promising to change

While he was inside, Ravinia was also forced to fund her son's drug habit as he "was taking drugs on credit".

She says she "had to pay because they would send people to collect their money" and they would make threats. Its Jude who told them, go to my parents, they will pay for me.

"They threaten you. They say that they will kill him."

It is not lost on Jude how lucky he is to have such a mother.

"Thank you, mum, for always being there, I know with you there, one day I will be a better person, I want to be a better person."

"Do it before it's too late," Ravinia tells him through her tears.

Jude promises her he will make a change. She is not convinced but will not give up on him.

Jail is not the ideal place to recover but it is not impossible. It does have a methadone programme, which can be used to treat heroin dependency, and some limited counselling sessions but Jude has got to want to do it.

The island's heroin problem contrasts with the beautiful scenery and holiday paradise

Methadone is also available to users outside prison. It is free to anyone who is registered, such is the extent of the epidemic.

In Victoria, every morning a bespoke white van with a distribution window on its side makes several stops around the city, where long queues form as people from all walks of life wait to get their medicine.

Surprisingly, in a nation held hostage by heroin, methadone is the only consistent support available to drug users.

For many Seychellois though, this daily dose is nothing more than a free morning hit which is incredibly dangerous. Using methadone and heroin at the same time can lead to a fatal overdose.

Taking methadone without a detox plan and counselling is rarely a good long-term recovery solution. Despite this, political decisions have led to the closure of all residential rehabilitation centres across the islands.

The president, who has been in office for two years now, blames his predecessors for the lack of much needed in-patient care.

He says that politics got in the way of dealing with the issue under the previous administration.

"But we have received a grant from the UAE to build a proper rehabilitation centre. And so we are going in that direction," Mr Ramkalawan says.

Cottage drug industry

The problem in Seychelles is so bad because the islands are caught up in well-established trafficking routes from Afghanistan and Iran to East Africa and Europe - but President Ramkalawan says the issue was exacerbated when a group of Iranian drug traffickers were incarcerated in the country.

"When they were here, they developed their network. After that, there were more Seychellois involved in the drug trade from Iran, and now today we find ourselves putting in so many resources just to fight those Iranian dhows coming into our waters to sell their poison."

Heroin mostly comes into Seychelles by boat - through its vast, porous water borders. With more than a million square kilometres of territorial seas, smugglers have easy access.

Once it makes land, it is largely sold out of small, improvised shops at the back of people's homes in the country's many ghettos.

It is basically a cottage industry, and whole communities are involved.

Drive five minutes off any main street - past the fancy hotels and expensive restaurants - and you can see for yourself. This drug is everywhere, and the fear is, worse is yet to come.

While heroin remains the front runner, for now at least because it is relatively cheap, there are new players on the market.

Crack cocaine and crystal meth are both beginning to be used and neither drug can be treated with methadone.

Jude signs up to the methadone programme hoping it will help him recover from his heroin dependency

In prison, a few days after his mother's visit, Jude decides to make good on his promise and give recovery another go.

He is taking a big step and trying to register for the prison's methadone programme - but not everyone qualifies.

Jude arrives at the prison medical centre visibly high. When the nurse tests his urine for heroin, it is no surprise when it comes back positive.

He is told he must stop using the drug altogether to be admitted onto the methadone programme. He agrees.

The next day he queues with his fellow inmates and takes his first dose.

Jude is also enrolled onto a counselling programme to give him the best chance at getting well.

His mother Ravinia is not holding her breath, she's been disappointed so many times before - but she is praying hard - that this time it sticks.

The BBC Africa Eye film Seychelles, Heroin and Me is on BBC Africa's YouTube page., external

Related topics

- Published21 November 2019

- Published12 January 2022

- Published28 October 2020

- Published21 July 2023