Kenya sickle cell: Fighting to dispel the myths around the disease

- Published

Sickle cell disease affects more people in countries in Africa than anywhere else in the world. BBC Africa Eye joined someone who helps give a voice to those with sickle cell in one town in Kenya, where nearly a quarter of the population lives with the genetic disease.

In the small town of Taveta, lodged in Kenya's Taita Hills close to the border with Tanzania, families sat on every available bench under a canopy at a local health clinic. Those who could not find space stood or sat on the grass.

"Who here has sickle cell?" asked Lea Kilenga Bey, the woman at the front, who they had all been waiting to hear from.

"All of us," they shouted in unison, meaning that they either carry the genetic mutation or are looking after someone who does.

In this busy market town at the base of Mount Kilimanjaro, with a population of just 22,000, nearly one in four of the residents have sickle cell, one of the highest rates of the genetic disease in the country.

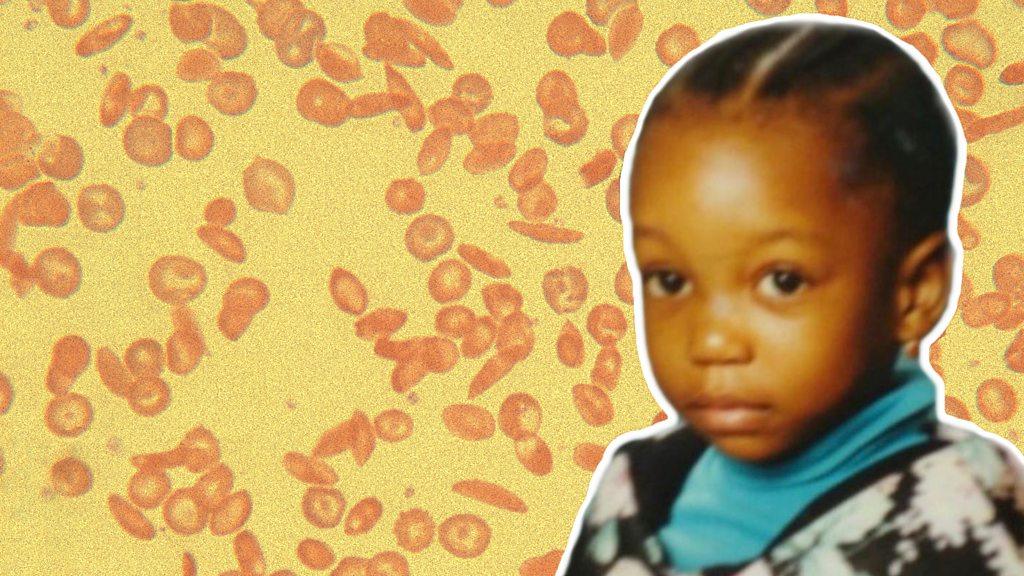

The red blood cells of some people with sickle cell, which are normally round, are shaped like a crescent moon or a sickle, and cannot transport enough oxygen around the body. Those with sickle cell can experience episodes of severe pain sometimes lasting weeks.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), two-thirds of people affected by sickle cell worldwide live in countries in Africa.

It is the most prevalent genetically acquired disease in the region, and the survival statistics are stark.

More than half of children born with sickle cell will die before the age of five, usually from an infection or severe anaemia. Some medical journals say child mortality rates are as high as 90%.

Lea Kilenga Bey wants better understanding and treatment for those with sickle cell in Taveta

A woman at the clinic put her hand up to ask a question.

"They say that someone with sickle cell cannot live beyond 20 years old. They only get to 15 years and most they can live is 18 years old."

Ms Bey pointed out that she was diagnosed with sickle cell at the age of six months and had survived - she is now in her 30s.

"It is a curse," another woman shouted out.

In 2017, Ms Bey founded the Africa Sickle Cell organisation, an non-governmental organisation focused on improving the lives of people with sickle cell. She regularly visits communities to spread awareness of the genetic disease, but she went back to Taveta, her hometown, to help support the people there.

"A lot of communities attribute sickle cell to ancestral curses, witchcraft," Ms Bey told BBC Africa Eye.

"This is a situation for any unknown thing in the community. People form their own stories around them. So, I had to go and tell people sickle cell is not witchcraft. It's not ancestral curses. It's something that we can solve."

One of the main challenges for people with sickle cell in Taveta, and other towns across Kenya, is access to medicine.

'Either food or drugs'

Daily treatment is needed for people to live normal lives: antibiotics to prevent infection, drugs to treat the blood cells and dietary supplements like folic acid to help with the anaemia.

Albert Loghwaru became a campaigner after his children were diagnosed with sickle cell and faced stigma

"The majority of people who have less $1 [£0.80] or $2 a day will not sacrifice the meal of their home to buy this expensive medicine," Ms Bey said.

"It's either the meal or the medicine."

She knows more than anyone what it is like to experience what is known as a sickle cell crisis - extreme pain caused by the blockage of a blood vessel, which can affect any part of the body.

Ms Bey has recorded video diaries of her sickle cell crises. Holed up in bed, without any medication, she stares at the camera, eyes half closed, trying to explain how excruciating the pain is.

She does not want others to suffer.

In Taveta, she also joined a group of people who were protesting at the local hospital, demanding better treatment.

"We are given expired medicine," one woman holding out a blister packet of tablets told her.

"So many people have died because they couldn't get proper medical care," another woman said.

"I told a friend I was giving my child medicine, but his eyes were still yellow. She discovered that the medicine had expired," said another.

Jaundice is a common symptom of sickle cell. Yellow eyes are a regular feature of this town.

Albert Loghwaru, 50, was the leader of the group. Two of his children had been diagnosed with sickle cell. They were then stigmatised despite so many in Taveta living with the disease.

"People around here would call us two things. It's either we had demons that were sucking blood from our child, or we are HIV positive."

Mr Loghwaru is determined in his fight to get access to treatment for his community.

"We have to find a way of helping these people."

As a result of his campaigning, along with Ms Bey, a joint haemophilia and sickle clinic finally opened in their town, the first in Taita Taveta county.

But this is not the end of the struggle for Ms Bey.

"We are just getting started. This is not a marathon. It is not the one who runs the fastest who will win. This is a relay race."

Related topics

- Published5 October 2021

- Published19 June 2022

- Published28 September 2019