Andrew Harding: A fond farewell to an uneasy South Africa

- Published

As he prepares to leave South Africa, the BBC's Andrew Harding reflects on his years in a country of increasingly stark contrasts - and on the struggle to find the right balance in reporting on such a complex nation.

Spring is almost here in Johannesburg.

Cold nights. Clear, bone-dry days. The honks and squawks of ibises and louries - shuffling silhouettes in the leafless trees.

After 15 years living in this beautiful, rough-and-tumble city, I'm about to leave.

The packers have been busy at our home just over the steep ridge that divides the old "downtown" from the tree-clogged northern suburbs.

"Shame," said the woman who came to inspect her removal team's speedy work. She shook her head. "So many families are leaving here these days."

She's not entirely wrong.

Concern about South Africa's struggling infrastructure, its weakening currency, and general economic malaise has prompted many wealthier families to consider emigrating or - as it's known here - "semi-grating" to the more prosperous city of Cape Town.

Last week, I was standing with my adorable, ever-so-slightly thuggish labrador at the vet's when an older lady came in, clutching something small and yappy.

Overhearing my conversation about kennels and crates and extravagant shipping costs, she announced to the room that she'd leave "this wretched country" too - in a heartbeat.

"But who can afford to these days?" she remarked.

It's now almost 30 years since the end of racial apartheid and the chaotic but near-miraculous birth of South Africa's young democracy. It's a shock to realise that I've been here for half of that journey.

I've always shied away from drawing grand or apocalyptic conclusions about where this - or any country on this continent - is heading.

South Africa, in particular, is a place of such extremes. There's such energy here, and resilience, and an enduring generosity of spirit.

At the same time, this is still a frighteningly violent nation, now also warped by corruption, and plagued by hunger.

How do you begin to boil all that down into a neat prediction?

Still, it is becoming more challenging to sustain the belief that South Africa - this charming, troubled, rainbow nation - will simply continue to muddle, endlessly, through.

South Africa's government has struggled to bring down unemployment levels

The unemployment rate here is comfortably the highest in the world. At 42%. Let that sink in.

Key infrastructure systems - water, rail transport, electricity - are in dire straits. Schools too. And this is - officially, and notoriously - the most unequal country in the world.

Just up the road from our house, near the suburb of Rosebank, there's a big road junction. The traffic lights - they call them "robots" here - don't work much these days, because of the endless power cuts.

Instead, young men in ragged clothes try to direct the lines of expensive cars in return for the occasional coin.

It sort of works, like so much here. But this kind of patchwork resilience is hardly something to boast about.

Last week a woman and her three children were reportedly found dead in their tiny shack close to the Indian Ocean in the Eastern Cape. The police suspect that poverty and debt drove the mother to poison her kids before taking her own life.

The incident barely made the news.

Earlier this year, between trips to report on the war in Ukraine, I went for a drink with a couple of contacts. Older, wealthy businessmen who have close ties to the governing African National Congress.

We met on the terrace of their immaculate golf club, with a view north - towards the lumpy hills that hide most of the world's platinum deposits.

We argued about Ukraine, Putin, and Nato expansion - about the men's enduring nostalgia for the Soviet Union and its support for the anti-apartheid struggle.

Then one of the men looked out, beyond his beer and the putting on the 18th green, towards the glinting tin roofs of an impoverished and fast-growing shanty town - "informal settlement" is the term used here.

"Someday soon those people are going to come for us," he said, predicting an uprising far greater than the protests that engulfed several big cities in South Africa in 2021. "Things can't go on like this," he warned.

I sensed guilt in his voice. And sure enough, he admitted that his once beloved ANC - a party that helped liberate South Africa - had failed the challenges of democracy.

"The crooks have taken over," he said. "It should be put out of its misery - other leaders, other parties, should have come to power years ago."

This is a nation lulled by a sense of its own exceptionalism. Its history of overcoming impossible odds"

There are elections here next year. And right now, opposition parties are trying to overcome their differences and put up a united front. There's a good chance they'll do well. But then again, South Africa has heard that before. Many young, disillusioned people are simply choosing not to vote.

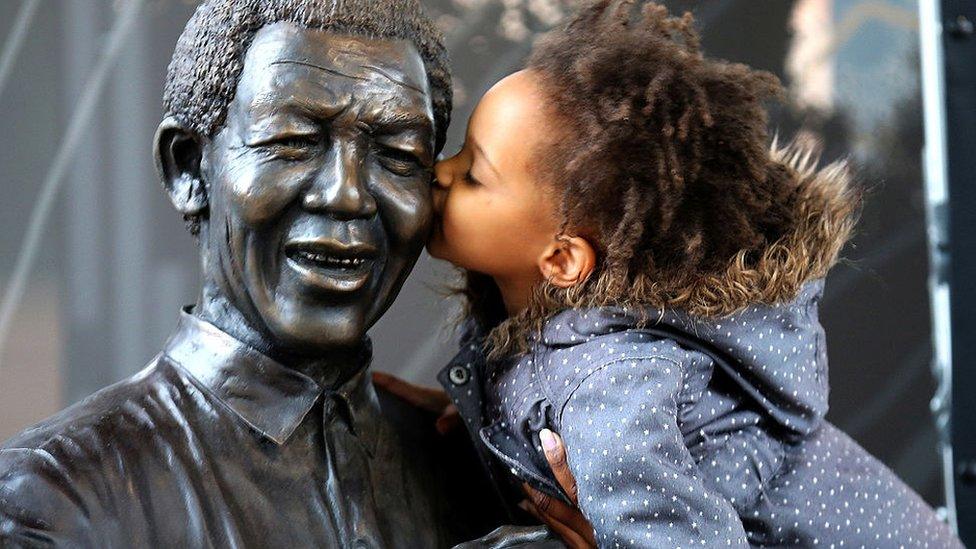

This can still be a profoundly inspiring country. But increasingly, it feels like the inspiration is mostly seen in the rear-view mirror - in looking back to past glories and past heroes. Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Oliver Tambo. This is a nation lulled by a sense of its own exceptionalism. Its history of overcoming impossible odds.

It's part of South Africa's enduring charm. But charm can be unhelpful. Nostalgia isn't creating any jobs.

After the packers had loaded the last box into the shipping container outside my home, we stood together in the sunshine. "You must come back!" said one of the men. "We'll fix our problems here. We'll even fix the load-shedding." That's another South African euphemism - for power cuts.

We laughed - half-hopefully - and shook hands, and I said: "Yes. I'll be back soon."

You can find Andrew's From Our Own Correspondent report on BBC Sounds and as a podcast - or you can listen to it on BBC World Service radio or on Radio 4 in the UK

Related topics

- Published24 May 2023

- Published10 July 2022

- Published19 June 2023