What a doctor's death in a lift may tell us about Africa's debt crisis

- Published

Friends of a doctor who died in Nigeria because the lift in her hospital accommodation fell nine floors with her inside are not surprised by a new study that reveals the country spends twice as much money on debt repayments as on health and education combined.

The major new report from the One Campaign, an anti-poverty group, focuses on the staggering amount of private loans that African countries have to service, often to the detriment of development.

It is not possible to draw a direct causal link between Nigeria's debt crisis and the death last month of Dr Vwaere Diaso, but every dollar spent servicing debt is one that cannot go into vital infrastructure.

Dr Diaso was just two weeks away from finishing her training at Lagos General Hospital when she died.

She had repeatedly complained to management about the crumbling infrastructure, power cuts and lack of funding in one of Nigeria's major public hospitals. She knew it was costing the lives of patients. She had no idea it would also cost her own.

"I remember Vwaere for her smile, she was the world's happiest person," her friend and colleague Dr Joy Aifuobhokhan tells us. "She actually loved her job and she loved to take care of people."

Dr Diaso suffered massive trauma after the elevator plummeted, but might have survived, had the hospital's oxygen supply and other facilities been working.

"I believe funding was a major issue in both our accommodation and the hospital in general. We complained to the management but the response we would get is that they did not even have enough funds to supply electricity to the hospital, let alone to spend money on the doctors' quarters."

It is just one example of a healthcare system in crisis. In 2018, Nigeria spent $5.9bn (£4.7bn) repaying loans. This year it is forecast to spend $8.4bn. That compares to just $2.2bn on education and $1.4bn on healthcare.

The One Campaign report estimates the poorest nations are paying 500% more for debt than they need to.

The organisation, which aims to reduce poverty particularly in Africa, has people like former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, former British Prime Minister David Cameron and former Meta boss Sheryl Sandberg on its board.

It is led by Gayle E Smith, a former adviser to three US presidents who also used to run US development spending. She says that the situation now is potentially bigger than the debt crisis of 2005.

"This is more countries simultaneously heading into crisis. And I think that this is going to have greater ripple effects, if you look at the number of countries that are at risk," says Ms Smith, warning of the economic and political consequences.

Why is it happening?

While the situation has been getting worse for a few years, the report says that rising interest rates in the US have supercharged the problem.

Rate rises cause the dollar to strengthen, in turn devaluing currencies like Nigeria's naira. Since most foreign debt is held in dollars, this instantly makes the problem worse.

On top of that, there is a well-established connection between the interest rate offered by the Federal Reserve, the US's central bank, and the rate commercial lenders will offer to other countries.

Add to this the soaring inflation seen around the world and a lack of finance from lenders like the World Bank.

"We've seen for the first time in 25 years an increase in extreme poverty," Ms Smith says about the impact already being witnessed.

"We saw a huge negative impact on health and education and the progress that's been made over the years.

"If you're spending over 90% of your budget on servicing debt, there's not much left to do anything with. And so breaking that cycle is near impossible."

The report calls for a massive increase in lending by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other global lenders.

The calls are similar to those made by the recent Bridgetown Initiative, spearheaded by Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley, who wants reform and modernisation of the international monetary system.

Of course, global institutions are not the only bodies being called on to reform.

"If you don't deal with issues around corruption, we're just going to be a lot of talk and no action," says Sam Chidoka, an expert on good governance in Nigeria.

He worries that the benefits of any debt reduction would not be passed to the people.

"There's nothing wrong with borrowing. It is what you do with money you borrowed. Has it been used to make the country more productive or are we borrowing to finance lifestyles, fly private jets and run large convoys for government functionaries?"

The issue of corruption is one the report does not deal with directly, but not one Ms Smith shies away from.

"There's no question that there needs to be transparency around the money that is provided. Policy and governance is a problem, but it is not the problem."

Many will be reminded of the Make Poverty History campaign of 2005, and with good reason. The report's authors helped set up that global movement, which saw a landmark deal on debt. While that did have a lasting impact, things are possibly even worse than they were before that was signed.

Nelson Mandela told a Make Poverty History rally in 2005: "Overcoming poverty is not a gesture of charity. It is an act of justice"

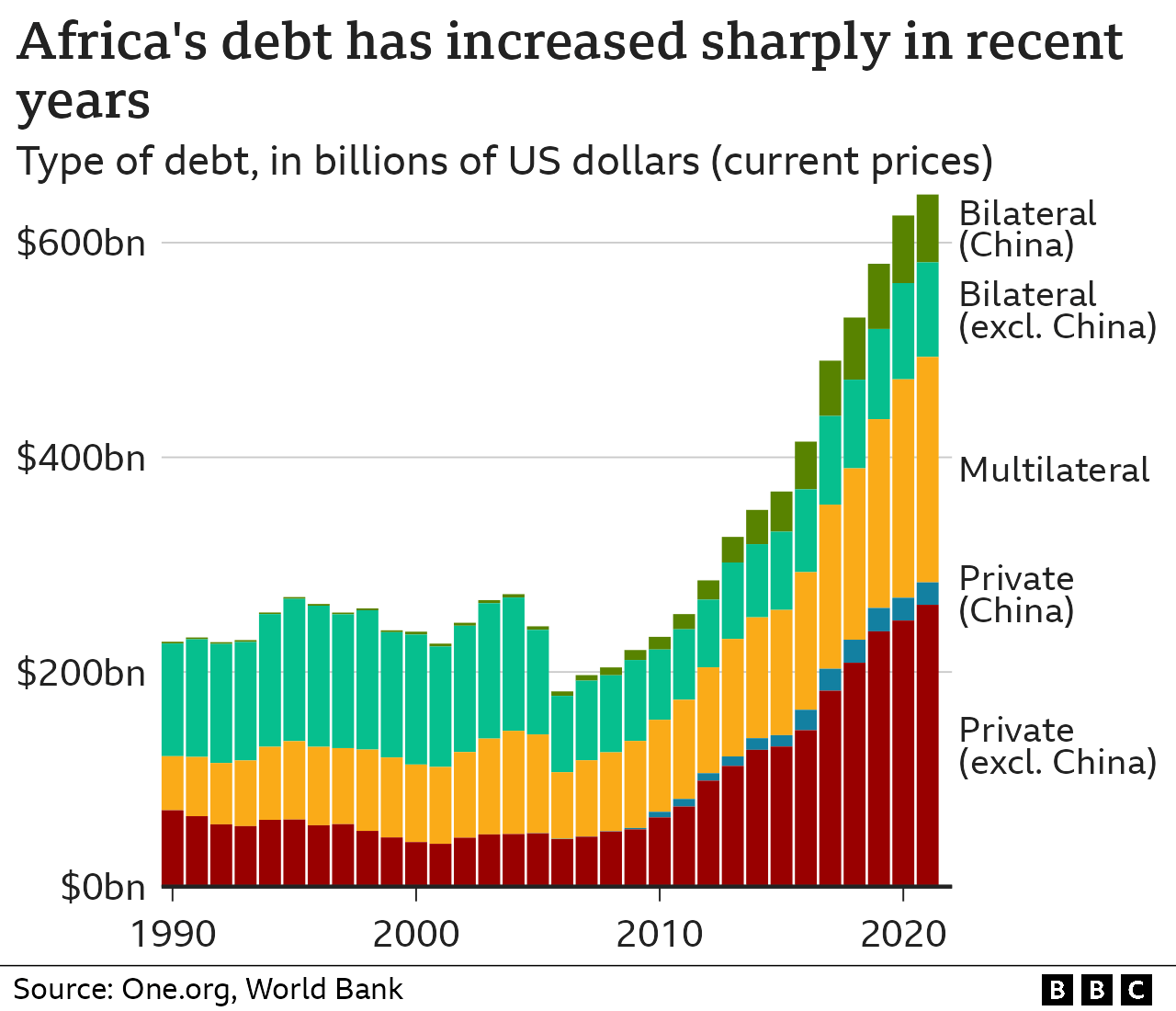

Following Make Poverty History, African external debt fell to a little more than $180bn. Now, it stands at $645bn, with private loans making up a far larger proportion of the total.

"We're not talking about the need for global charity," says Ms Smith.

"It is in the interest of Europe and the United States, Canada, the whole of the G7, plus indeed the G20, to see Africa develop."

That argument, that this is about enlightened self-interest rather than benevolence, is central to this report.

Debt-crippled economies fail to help tackle climate change or provide opportunities for their young people, who then seek opportunities in Europe or elsewhere.

That exodus is already being seen in Nigeria's healthcare system, with many young doctors seeking opportunities abroad because of poor pay and conditions. According to Dr Aifuobhokhan, her friend Dr Diaso was one of those who did not want to leave.

"Then this incident happened where we see that someone is clearly dying because of poorly funded facilities, no infrastructure or emergency responses."

Related topics

- Published30 January 2023

- Published2 April 2023

- Published6 January 2022

- Published18 May 2023

- Published23 June 2023