Congo cobalt: TikTokers quit vaping over mining concerns

- Published

Micah Ndango has stopped using e-cigarettes after five years of vaping

Dozens of young adults on TikTok are vowing to throw out their e-cigarettes and quit vaping - but not for health reasons.

"In my effort to help [the Democratic Republic of] Congo, I'm quitting vaping," Micah Ndango, who has been vaping for five years, says in a video that has been viewed more than 15,000 times.

"My sister just took my last vape so I'll be documenting my vape-quitting process on here," the 21-year-old pledges.

DR Congo, a central African country, is the world's main source of cobalt, a key component of the lithium-ion batteries used in mobile phones, electric vehicles and many models of e-cigarette.

It is also home to more than 100 million people and currently faces what the UN says is one of the "largest humanitarian crises in the world".

Dozens of armed groups have long plagued DR Congo's mineral-rich east and this year heightened conflict has pushed the number of people forced to flee their homes to a record 6.9 million people, UN data, external shows.

Civilians are also being targeted - just last week 14 villagers were killed by suspected Islamist militants.

As reports of the recent unrest spread, social media users have been questioning the role international companies and consumers have in DR Congo's woes.

"The first time I heard about the impacts of cobalt mining in Congo was from a TikTok [video]," Ms Ndango, who lives in the United States, tells the BBC.

"After watching that TikTok I did my own research on the subject."

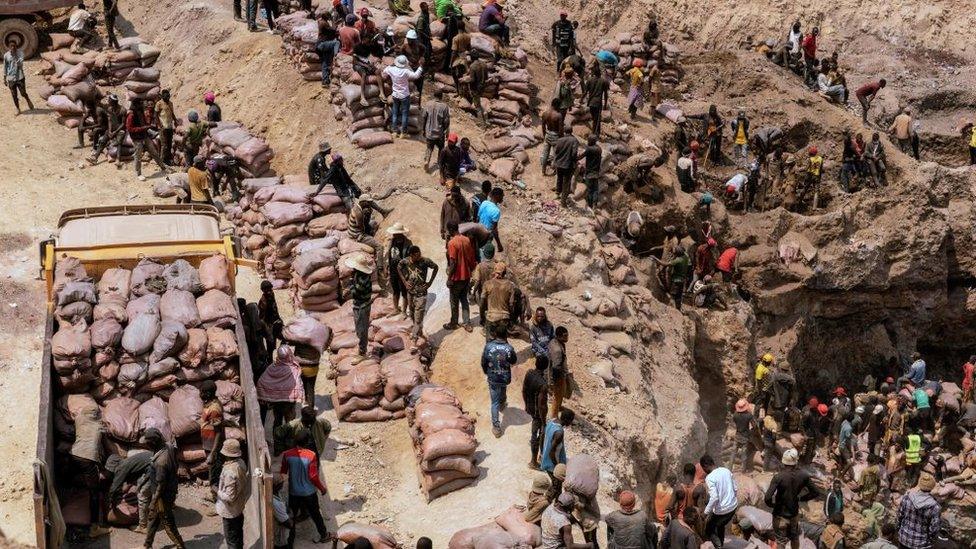

Mines in DR Congo supply around 70% of the world's cobalt, according to the US government

In September, a report from Amnesty International, external found multinational companies mining for copper and cobalt in DR Congo had forcefully evicted entire communities.

Amnesty also found human rights abuses - for instance numerous villagers who refused to leave their homes said they were beaten by Congolese soldiers.

And last year, the US Department of Labor added lithium-ion batteries to its "list of goods produced by child labour or forced labour", external, based on its evidence of children mining cobalt in DR Congo.

"Thousands of children miss school and work in terrible conditions to produce cobalt for lithium-ion batteries," the department reported.

It said entire families might work in Congolese cobalt mines: "When parents are killed by landslides or collapsing mine shafts, children are orphaned with no option but to continue working."

Given the scale of the practice, Ms Ndango recognises it might be difficult for online activism to drive lasting change on the ground. However, her videos will raise awareness at the very least, she says.

"You never know who is on the other side of that phone and the change they may be able to make.

"I believe that I have the ability to spread awareness and social media is an incredibly powerful communication tool, so why not use it?"

Videos of TikTokers like Ms Ndango pledging to quit vaping have indeed gained widespread attention. One of the most watched - by creator @itskristinamf - has been viewed more than 1.7 million times.

On Ms Ndango's own videos, dozens of TikTok users have responded with comments like: "You aren't alone. Just started the same thing" and "GIRL I QUIT TODAY TOO WE IN THIS TOGETHER".

Many e-cigarettes use lithium-ion batteries

However, Christoph Vogel, author of Conflict Minerals, Inc.: War, Profit and White Saviourism in Eastern Congo, believes such digital activism is a "double-edged sword".

It can draw mass attention to important issues, but can often only do so through "massive simplification", he tells the BBC.

"There are widespread human rights violations, including child labour, in the context of cobalt mining - adding to significant health hazard," says Mr Vogel, a UN Security Council expert on DR Congo who spent years working in the country.

"But this is common to mining in general and it would be misleading to assign that to cobalt, per se."

Online activism also risks stripping agency from the communities it means to help while "Western advocates and the swarm intelligence of online users dominate the narrative".

Ms Ndango acknowledges this point.

"There's so many layers to the issues in DR Congo but when spreading awareness online, people are going to oversimplify things to fit the 60 seconds they have."

She laments that the people impacted the most from cobalt mining in DR Congo might not have the means to tell their own stories en-masse, but urges others to "use your power for good".

"One post can reach an entire nation," she adds.

You may also be interested in: