Nelson Mandela and how young South Africans view his legacy

- Published

"I have a love-hate relationship with the old man," says Sihle Lonzi, 26, of Nelson Mandela on the 10th anniversary of the death of South Africa's first black president.

Mr Lonzi is the leader of the student wing of South Africa's third biggest party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), and part of a generation that grew up after the racist system of apartheid ended in 1994.

Too young to have witnessed the liberation struggle or Mr Mandela's presidential years, and unencumbered by the nostalgia of previous generations, Mr Lonzi and his peers have been re-evaluating the anti-apartheid icon's legacy.

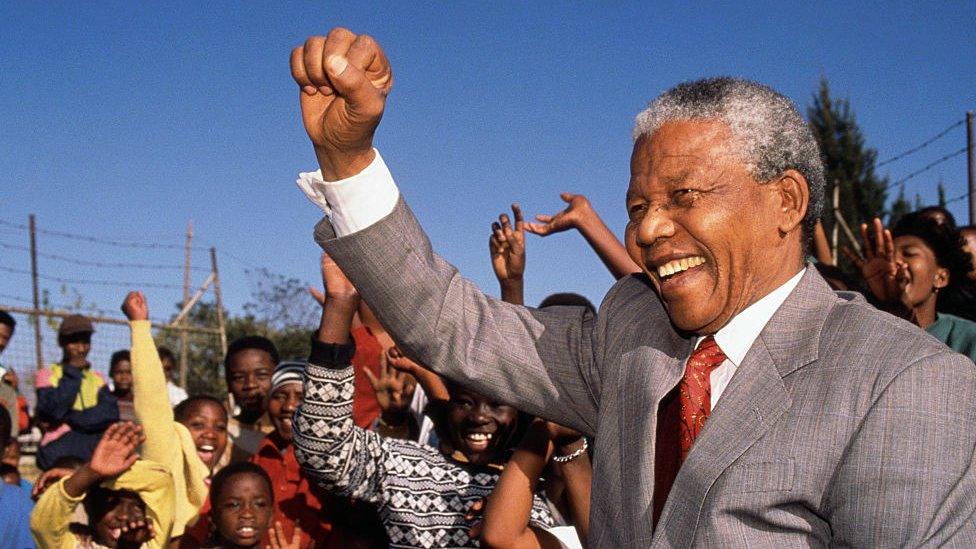

Mr Mandela is cemented in history as one of the most-influential people of all time.

He led the fight against apartheid, spent more than 27 years in prison, and became South Africa's first democratically elected president in 1994 after negotiating an end to white-minority rule.

He stood down after one presidential term and died at the age of 95 on 5 December 2013, to the wails of a nation mourning their beloved father figure.

Cautiously choosing his words, Mr Lonzi tells the BBC that Mr Mandela gave the people of South Africa political freedom, but he failed to give them economic freedom.

Adamant not to label him a "sell-out", as some critics have done over the years, Mr Lonzi does say that Mr Mandela compromised too much during negotiations with the white-minority government.

The disappointment is apparent in Mr Lonzi's voice as he says he wanted Mr Mandela to have "pushed harder" for an agreement on land and wealth distribution, as he had initially promised to do.

Sihle Lonzi says Nelson Mandela should have done more to achieve black economic empowerment

In 1990, Mr Mandela confirmed the intentions of the African National Congress (ANC) - the liberation movement which he led into government in 1994 - to nationalise mines, banks and "monopoly industries", external.

But following concerns that nationalisation would have a ruinous effect on the economy and to ensure a smooth transition of power, Mr Mandela dropped the policy.

For Mr Lonzi, this has left South Africa as one of the most unequal countries in the world.

As it stands, about 10% of the population own more than 80% of the wealth, according to a 2022 report by the World Bank.

It says that race remains a key driver of economic inequality.

The white-minority population has retained most of the wealth they acquired during apartheid.

Mr Lonzi says because of this he feels the economy is heavily weighed against Gen Z, especially black people.

"There is a massive gap between the promises Nelson Mandela made and the reality we live in," he says.

The reality Gen Z has been saddled with is an unemployment rate of around 60%, a murder rate that has reached its highest in 20 years and rampant drug abuse.

Anita Dywaba, 24, a United Nations Foundation Next Generation Fellow, tells the BBC the current state of South Africa has left a single question on a constant loop in her mind: "Will I live long enough to have a family of my own?"

Anita Dywaba says Nelson Mandela's legacy is "contested"

Many of her friends lost their lives because of violent crime, fuelled by the dire economic situation.

But Ms Dywaba does not blame Mr Mandela for South Africa's failings. She insists that he did what he had to do to end apartheid peacefully.

Her admiration for his sacrifices has never wavered even as "Nelson Mandela's legacy is contested amongst Gen Z", she says.

Her mother fought in the liberation struggle, and she passed on more than just genetics, but also a deep admiration for Mr Mandela, even in the face of criticism.

A leader of the ANC youth wing in Eastern Cape province, Mzobanzi Nkwentsha, says his father had a painting of Mr Mandela in the family living room to ensure that every visitor saw it.

His voice pitches slightly as he tells the BBC that he will hang a photo of the former president when, one day, he has his own home.

"I have always revered Nelson Mandela as the leader of the South African revolution and a great statesman," Mr Nkwentsha says.

Mzobanzi Nkwentsha wants the next generation to build on the foundation Nelson Mandela laid

He lists Mr Mandela's achievements as improving education and housing for black people, and providing social grants to the financially needy.

He says these policies still "resonate with the poorest of the poor" in South Africa.

Mr Nkwentsha counters the argument that Mr Mandela compromised too much in talks with the apartheid regime, saying that if peace was not achieved a civil war would have erupted.

He says the baton has been passed on to his generation to fight for economic change.

Mandela magic

But can the ANC still conjure Mandela magic to garner votes in next year's general election, especially among Gen Z?

Mr Lonzi does not think so.

"People have been hypnotised by the aura of Mandela. But it has reached its expiry date," he says, though he adds that older voters may still be swayed by it.

Mathabo Mahlo says despite criticism of Nelson Mandela, he still inspires hope

Many critics say the seeds of corruption in South Africa were planted during Mr Mandela's presidential tenure - from 1994 to 1999 - and he turned a blind eye to it.

In 1996, Bantu Holomisa - then a prominent ANC leader and a deputy minister in the government - accused a member of Mr Mandela's cabinet of taking a bribe from a casino magnate during the apartheid era.

Mr Mandela sacked Mr Holomisa from the government, and the ANC expelled him for bringing the party into disrepute.

The late president's loyalty to the ANC was etched into his very being, even if it was to the detriment of his own reputation.

The father of the nation was presented to Gen Z as a man, a myth, a legend, a saviour. But there is no doubt that they now harbour mixed feelings towards him.

Mathabo Mahlo, a 24-year-old master's student at South Africa's Rhodes University, tells the BBC that Gen Z is "disillusioned" and very critical of Mr Mandela's legacy.

But she admits that he still evokes a sense of hope for her, and that change can happen again for South Africans, at a time when they so desperately need it.