Nigeria's mass abductions: What lies behind the resurgence?

- Published

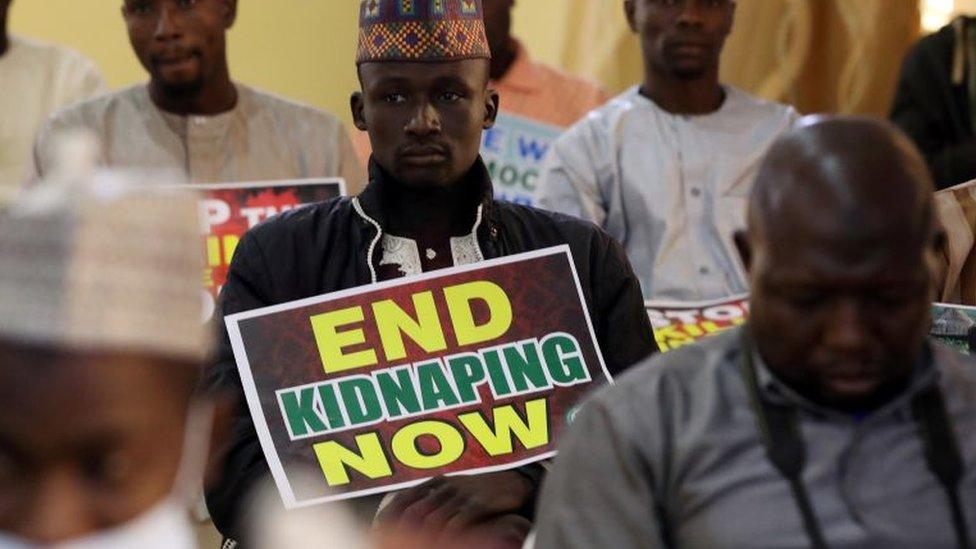

Family members of those who had been abducted from a school in Kaduna gathered to meet the state governor on Thursday

Nigeria is once more being rocked by mass abductions.

Twice in one week, gangs of motorcycle-riding armed men, operating from forests in two different places in the north of the country, kidnapped hundreds of people.

First on Wednesday we got news from a remote town in Borno state in the north-east that suspected militant Islamists had seized women and children from a displaced persons camp who were searching for firewood. It took several days for the news to emerge because the local mobile phone masts had been destroyed.

Then the following day, more than 280 children, aged between eight and 15, and some teachers, were taken away by gunmen from a school hundreds of miles away in the north-western state of Kaduna into a nearby forest.

There are reports locally that this attack was carried out by militants from the al-Qaeda-linked Ansaru group.

In recent months, there had been a lull in this type of mass kidnapping that had plagued Nigeria since the notorious abduction of nearly 300 girls from a school in Chibok in April 2014 which captured international headlines.

But now, it's déjà vu as the 10th anniversary of that tragedy looms.

The mass abduction in Kaduna is the biggest from a school since 2021.

So why is there a resurgence of this kidnapping that is endangering the lives of the most vulnerable Nigerians?

It is hard to discern a pattern from the coincidental timing of two apparently unconnected incidents, but it is a reminder that the threat has not gone away.

The fact that they happened just days before the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan may be significant.

Those who have been kidnapped and freed in the past have talked about being forced to do cooking and other menial jobs in the forest camps.

But in general, kidnap-for-ransom in Nigeria is a low-risk, high-reward business. Those abducted are usually freed after money is handed over, and the perpetrators are rarely arrested.

This is despite the fact that paying a ransom to free someone has been made illegal.

In all, more than 4,700 people have been kidnapped since President Bola Tinubu came into power last May, risk consultants SBM Intelligence have said.

Campaigners have called on the authorities to do more to end the insecurity

Kidnapping has become a lucrative venture for people driven by economic desperation to raise funds.

Apart from ransoms of money, gangs have in the past demanded foodstuffs, motorcycles and even petrol in exchange for the release of hostages.

"Nigeria's poor economy creates the conditions for kidnapping. Over the past year, the government has not been able to fix its foreign exchange problem," William Linder, a retired CIA officer and head of 14 North, an Africa-focused risk advisory, told the BBC.

"Food prices have skyrocketed, especially over the past six months. The perception of corruption continues."

Alex Vines, director of the Africa programme at the Chatham House think-tank agrees.

He said that the recent attacks can be tied to Nigeria's underperforming economy and the inability of the forces to disrupt the kidnapping gangs' activities.

Rising food costs have been worsened by the farmers not being able to access their fields to grow food as they fear being attacked or kidnapped.

"In large swathes of these areas, armed gangs have supplanted both the government and traditional rulers as the de facto authority," Dr Vines explained.

The gangs often extort money from people, but the fact that they are unable to farm means there are fewer funds available, which may explain the gangs turning to kidnapping.

Likewise, the shrinking of the Lake Chad basin and the spreading of the Sahara Desert southward has led to the disappearance of arable farmland and a scarcity of water.

"These pressures only add to the woes of many, especially in the north. This pushes people to seek alternative means of income. Unfortunately, kidnapping for ransom is one," Mr Linder said.

The gangs are aided by the fact that Nigeria's borders are porous and insecure. Islamist violence in the wider region has added to the insecurity.

The vast forest reserves in the border regions have been turned into operational bases for the criminals.

"Nigeria needs to work with its neighbours," said Bulama Bukarti, a senior conflict analyst at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

"Without transnational co-operation especially with Niger, Cameroon, Chad, including in the north-western part of Nigeria's border, these incidents will continue to repeat themselves."

But that alone would not help Nigeria defeat the gangs, Mr Bukarti added. The authorities also need to be willing to bring perpetrators to justice.

"We have never seen a gang leader arrested and prosecuted. It's lucrative. More people will join, and impunity will increase," he said.