Sierra Leone sexual violence: What difference did the national emergency make?

- Published

Sierra Leone's President Julius Maada Bio took the bold step of declaring a national emergency over rape and sexual violence in 2019. Five years on, BBC Africa Eye explores whether survivors of attacks are getting justice.

Warning: This article contains details some readers may find upsetting.

In the city of Makeni, a three-hour drive east of Sierra Leone's capital, Freetown, a young mother sits outside her home with her three-year-old daughter.

Anita, which is not her real name, describes the day in June 2023 when she found her toddler with blood dripping from her nappy.

"I worked for this woman, and she gave me an errand that Saturday morning to go to the market," she says, explaining that she then left her child with her employer and her 22-year-old son.

"He took my child, he said, to buy sweets and biscuits for her. It was a lie."

When she got back, she realised her daughter was missing. After searching for her for some time, they were reunited but the 22-year-old mother could see that the toddler was bleeding. She took her to the hospital and after two rounds of stitches, it was confirmed she had been raped.

"The nurses began checking the child, and they said: 'Oh my God, what has this man done to this child?' The doctor who was treating my child even cried."

Anita went to the police but the man fled and a year on the police have not been able to find him.

"The president created a law so that whoever rapes children, should be arrested and sent to jail," she says, angry that nothing appears to have been done.

She is referring to a tougher sexual offences law created five years ago after President Maada Bio declared the emergency over rape.

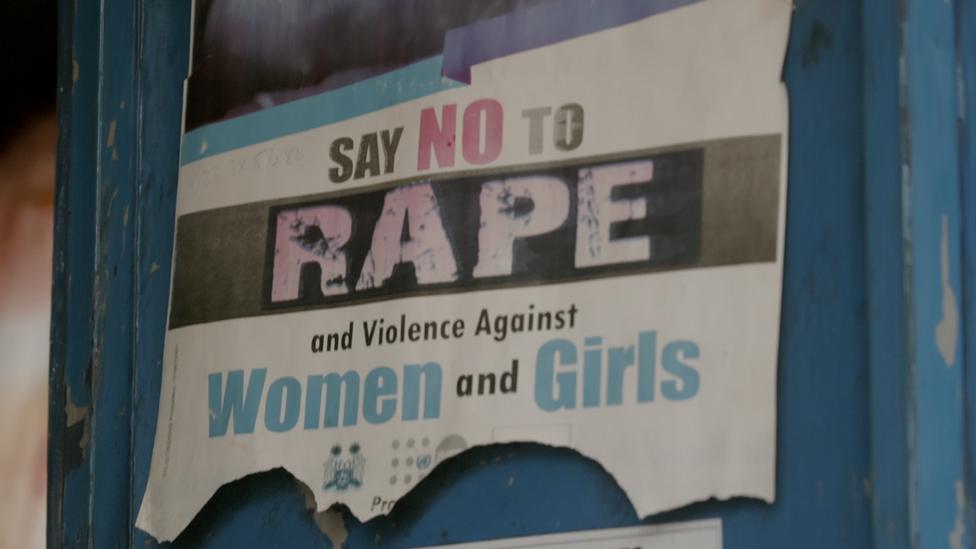

The laws are in place but the authorities lack the resources to deal with the issue

It followed protests in December 2018 when hundreds of people wearing white T-shirts emblazoned with the words "Hands off our girls" marched through Freetown.

News of another child rape had shocked the nation - a five-year-old girl who was left paralysed from the waist down. It was reported at the time that cases of sexual violence had almost doubled within a year, a third involving children. Sierra Leoneans had had enough.

The four-month long state of emergency from February 2019 allowed the president to divert state resources into tackling sexual violence.

An updated Sexual Offences Act brought in stricter penalties for sexual assault.

Rape sentences were increased to a minimum of 15 years, or life if it involved a child. A Sexual Offences Model Court to fast-track trials was created in Freetown the following year.

There appears to have been some progress - reported cases of sexual and gender-based violence have gone down by almost 17%, from just over 12,000 in 2018 to just over 10,000 in 2023, according to police statistics.

Creating increased awareness and new structures is one thing, but making sure that people, like Anita's daughter, get justice is another.

The Rainbo Initiative is a national charity that works with survivors of sexual violence. It says that in 2022 just 5% of the 2,705 cases it handled made it to the High Court.

One of the issues is the resources available to those who are supposed to enforce the law.

At the police station in Makeni where Anita reported her daughter's rape, Assnt Supt Abu Bakarr Kanu who leads the Family Support Unit (FSU) says they get around four cases of child sexual assault each week.

Doing the right thing at the right time is a challenge"

The big challenge his team faces is a lack of transport to physically go and arrest suspects.

He co-ordinates all seven police divisions in the region and between them they do not have a single vehicle.

"There are times the suspect is available but because of lack of vehicles you can't reach that suspect to arrest him or her," says Assnt Supt Kanu.

"Doing the right thing at the right time is a challenge."

Like many in Sierra Leone, he was impressed with the government action that followed the state of emergency.

"We have enough… good laws and policy, but the structure and personnel are the challenge for us to holistically address the issues of sexual and gender-based violence in Sierra Leone."

Even if an alleged perpetrator is apprehended, to get them before a judge is an even bigger struggle.

In order for the case against a rape suspect to be heard, there is only one person in the country who can sign the documents - the attorney general. It was meant to speed up the process and get the cases straight to the courts, but it has created a different bottle-neck.

"Presently it is not possible to have any other law officer or any other counsel to sign an indictment for sexual-related offences," says State Counsel Joseph AK Sesay, a lawyer employed by the government.

"The 2019 amendment stipulates that it is only the attorney general that can rightly sign an indictment. So that has been posing a challenge when it comes to getting the indictments to courts."

The new laws... have led to the overall feeling that we're not in the deep, dark days of 2019"

Information Minister Chernor Bah admits this is not a perfect process but says it is "a process that we'll continue to improve on".

Challenged on the question that many believe little has changed when it comes to getting justice for rape survivors, he acknowledged that "in some communities people feel that way".

But he rejects the idea that there has been no progress.

"I think the systemic reforms that we've put in place are there. The new laws are there. And those steps, I think, have led to the overall feeling that we're not in the deep, dark days of 2019."

For Anita, back in Makeni, it has been nearly a year since her toddler was raped.

She has had no new information from the police, so has resorted to posting the alleged suspect's photo on Facebook.

"I want people to help me search for the boy. I'm tormented and I am not happy. What has happened to my child, I don't want it to happen to any other child."

You can watch the full BBC Africa Eye documentary Behind Closed Doors - Sierra Leone's Gender-Based Violence Epidemic on the BBC Africa YouTube channel, external.