Obituary: King Bhumibol of Thailand

- Published

King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand was the world's longest reigning monarch.

He was viewed by his subjects as a stabilising influence in a country that saw numerous military coups during his reign.

Despite being seen as a benign father figure who remained above politics, he also intervened at times of heightened political tension.

And although he was a constitutional monarch with limited powers, most Thais regarded him as semi-divine.

Bhumibol Adulyadej was born in Cambridge in the US state of Massachusetts on 5 December 1927.

His father, Prince Mahidol Adulyadej, was studying at Harvard when his son was born.

The family later returned to Thailand, where his father died when he was just two years old.

He became engaged to Sirikit in 1948

His mother then moved to Switzerland, where the young prince was educated.

As a young man he enjoyed cultured pursuits, including photography, playing and composing songs for the saxophone, painting and writing.

The status of the Thai monarchy had been in decline since the abolition of its absolute rule in 1932, and there was a further blow when his uncle, King Prajadhipok, abdicated in 1935.

The throne passed to Bhumibol's brother, Ananda, who was just nine years old.

Figurehead

In 1946, King Ananda died in what remains an unexplained shooting accident at his palace in Bangkok. Bhumibol acceded to the throne when he was 18 years old.

His early years as king saw Thailand ruled by a regent, as he returned to his studies in Switzerland. While on a visit to Paris he met his future wife, Sirikit, daughter of the Thai ambassador to France.

The couple married on 28 April 1950, just a week before the new monarch was crowned in Bangkok.

He was a keen musician, here playing with bandleader Benny Goodman

For the first seven years of his reign, Thailand was ruled as a military dictatorship and the monarch was little more than a figurehead.

In September 1957, Gen Sarit Dhanarajata seized power. The king issued a proclamation naming Sarit, military defender of the capital.

Under Sarit's dictatorship, Bhumibol set about revitalising the monarchy. He embarked on a series of tours in the provinces, and lent his name to a number of developments, particularly in agriculture.

For his part, Sarit reinstated the custom that people crawled on their hands and knees in front of the monarch. and restored a number of royal ceremonial occasions that had fallen into disuse.

Overthrow

Bhumibol dramatically intervened in Thai politics in 1973 when pro-democracy demonstrators were fired on by soldiers.

The protesters were allowed to shelter in the palace, a move which led to the collapse of the administration of then-prime minister, Gen Thanom Kittikachorn.

But the king failed to prevent the lynching of left-wing students by paramilitary vigilantes three years later, at a time when the monarchy feared the growth of communist sympathies after the end of the Vietnam War.

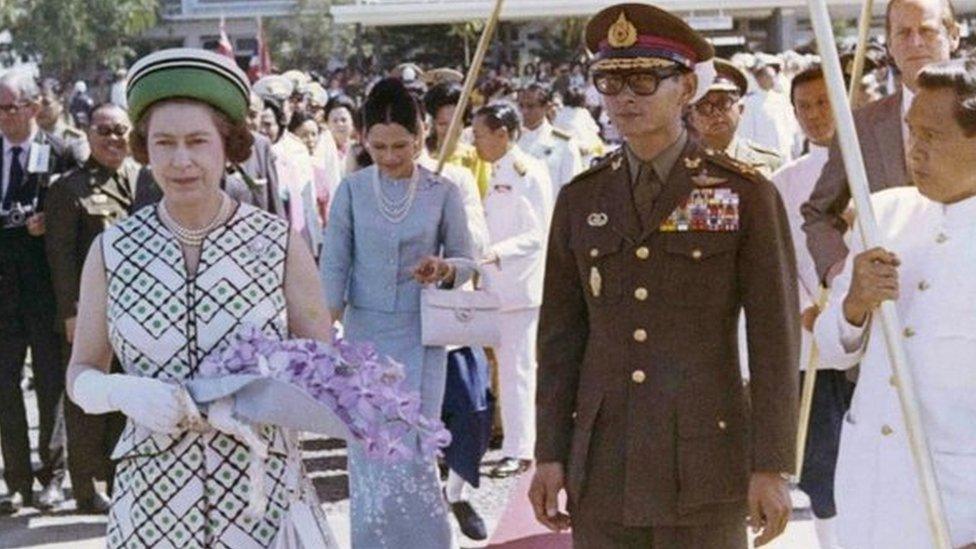

Queen Elizabeth made a state visit to Thailand in 1972

There were to be further attempts to overthrow the government. In 1981, the king stood up to a group of army officers who had staged a coup against then prime minister, Prem Tinsulanond.

The rebels succeeded in occupying Bangkok until units loyal to the king retook it.

However, the tendency of the king to side with the government in power caused some Thais to question his impartiality.

Bhumibol intervened again in 1992, when dozens of demonstrators were shot after protesting against an attempt by a former coup leader, Gen Suchinda Kraprayoon, to become prime minister.

The king called Suchinda, and the pro-democracy leader, Chamlong Srimuang, to appear in front of him, both on their knees as demanded by royal protocol.

Suchinda resigned and subsequent elections saw the return of a democratic, civilian government.

During the crisis that erupted over the leadership of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra in 2006, the king was frequently asked to intervene but insisted this would be inappropriate.

He was a keen supporter of agriculture

However, his influence was still viewed as pivotal when the election Mr Thaksin had won that April, was annulled by the courts.

Mr Thaksin was eventually deposed in a bloodless coup, in which the military pledged their allegiance to the king.

In the years that followed, the king's name and image were invoked by factions both for and against Mr Thaksin, as they jostled for power.

The entire country joined lavish celebrations to mark King Bhumibol's 80th birthday in 2008, reflecting his unique status in Thai society.

Reverence

Gen Prayuth Chan-ocha seized power in a coup in May 2014 and was made prime minister by the military-appointed parliament a few months later.

He promised far-reaching political reforms to prevent a return to the instability of recent years.

But critics suspected his real priority was to destroy the party of Mr Thaksin and to ensure that the royal succession took place smoothly.

The standing of the monarchy was strengthened during his reign

The public reverence for King Bhumibol was genuine but it was also carefully nurtured by a formidable public relations machine at the palace.

There were harsh "lese-majeste" laws that punished any criticism of the monarchy and which restricted the ability of foreign and domestic media to fully report on the king.

During his long reign, King Bhumibol Adulyadej was faced with a country continually racked by political upheaval.

It said much for his skills as a diplomat, and his ability to reach out to ordinary people in Thailand, that his death leaves the country's monarchy far stronger than it was at his accession.