Who is fanning Tibet's flames?

- Published

- comments

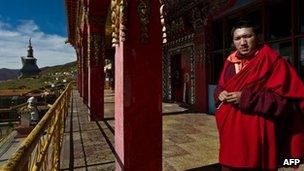

The self-immolations have taken place near Tibetan monasteries like this one in Sichuan province

It was just a few minutes to one in the afternoon last Thursday.

Standing at a road junction in a town in Sichuan, in south-western China, was a young woman.

Without warning, she doused herself in petrol - she may even have drunk some - and then set fire to herself.

Tibetans say her name was Palden Choetso; she was 35 years old and had been a Tibetan Buddhist nun since the age of 20. Official Chinese reports gave her name in Chinese as Qiu Xiang.

Her death, it is thought, was swift and, one can only imagine, agonising.

So what drives someone to such an awful, desperate step? In fact, what drives 11 people to willingly burn themselves like this?

'Desperate situation'

That is what has happened so far this year in Aba and Garze (known in Tibetan as Ngaba and Kardze), both Tibetan areas of Sichuan.

Two of those who set fire to themselves have been nuns; nine of them were men, monks or former monks. Six of the eleven have died, the fate of the others is not know.

Palden Choetso (or Qiu Xiang) was the oldest; the youngest was 18.

This wave of self-immolations is unprecedented. So what is happening in these Tibetan communities? Who or what is fanning the flames?

China is keeping foreign journalists out of the areas. Tibet's exiled leadership says those who set fire to themselves shouted slogans as they did so: "Long live his holiness the Dalai Lama", "Let the Dalai Lama return to Tibet", and "Freedom for Tibet".

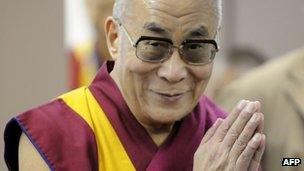

The Tibetan spiritual leader says Beijing's policies have created a desperate situation

On Monday the Dalai Lama, speaking in Japan, said: "Some kind of cultural genocide is taking place... that is why you see these sorts of sad incidents happen, due to the desperateness of the situation."

Tibet's Prime Minister-in-exile Lobsang Sangay has been more explicit. "The monks and nuns who immolated themselves were sacrificing their bodies to draw the world's attention to Chinese repression in Tibet," he said.

"While the leadership in exile does not encourage self-immolation," Mr Sangay added, "we must focus on the causes... the continuing occupation of Tibet and the Chinese policies of cultural repression, cultural assimilation, economic marginalisation and environmental destruction."

'Inciting'

Unsurprisingly, China has pointed the finger straight back. The Xinhua news agency said of Qiu Xiang's death that "initial investigation showed the case was masterminded and instigated by the Dalai Lama clique, which has plotted a chain of self-immolations in the past months for splitting motives".

China's Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei criticised the exiled leaders for "refusing to denounce the self-immolations", charging that instead "they are publicising these events, and inciting further immolations".

The US Department of State has weighed in too, saying it has "repeatedly urged the Chinese government to address its counter-productive policies in Tibetan areas that have created tensions".

Amid the finger-pointing one thing is clear. The immolations have gone on and on.

The first was by a 20-year-old monk called Phuntsog in March. China responded by deploying thousands of armed police, locking down monasteries, pressuring many monks to undergo "patriotic re-education", and shipping hundreds more away to an unknown fate.

But none of that has stopped the burning. There is, it seems despair among some Tibetans. Why else would a 20-year-old, or a 35-year-old, choose - willingly, it seems - to die in petrol-fuelled flames lit by their own hands?

Are they a few manipulated by leaders outside Tibet or are they indicative of broader discontent?

China says it is working to bring progress and development to Tibetan areas. It is hoping those, and a firm hand when it comes to security, will end the tensions. But what if its policies are not working?

The question we should perhaps be asking then is not so much who is fanning the flames, but rather what will douse them?