China's Chen Guangcheng: Isolated but not forgotten

- Published

The BBC's Michael Bristow was stopped by the authorities when he tried to meet Chen Guangcheng

The three men acted swiftly and efficiently - they had a job to do. They yanked open the car door, barked a few orders and then snatched equipment from out of our hands: cameras, mobile phones and recording devices. We were told to stay put while one man radioed for help.

This was the scene at the entrance to the village of Dongshigu in China's Shandong Province, where a self-taught legal activist has been virtually imprisoned in his own home.

Chen Guangcheng, blind since childhood, is watched by plainclothes security officers, who appear to be acting outside the law - but with the authorities' approval.

Activists have been trying to visit him for months; many say they are beaten up for their efforts. The BBC saw the kind of men they say they come up against.

Mr Chen made his name by helping women who said they had been forced to have abortions or undergo sterilisation. He helped expose the harsher side of China's family planning policies.

His activism eventually landed him in jail. The 39-year-old was sentenced to more than four years in 2006 for disrupting traffic and damaging property.

He denied the allegations, with many believing the charges were brought simply to silence him.

The activist was released last year, but, along with his wife and daughter, has spent much of the time since confined to his home.

Although he is isolated from the world, unable to leave a village surrounded by orchards and hills, Mr Chen has not been forgotten.

A steady trickle of activists has been making its way to his home, near the booming city of Linyi, for the past several months. But few get through the security cordon.

Personal grievance

A group of 37 tried to visit at the end of October and were attacked by about 100 unidentified individuals, according to the New York-based organisation Human Rights in China.

One of those who went along was Liu Li, a 49-year-old who has been living in Beijing for the last six months, pursuing his own personal grievance against the government.

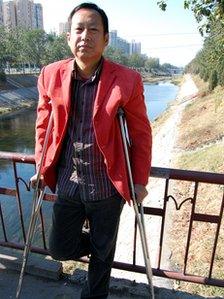

Liu Li was beaten up when he tried to visit Chen Guangcheng

Mr Liu is still on crutches, the result of being beaten up outside Mr Chen's village, he said. But he does not regret trying to visit him.

"Chen Guangcheng represents all that's wrong and unfair when it comes to human rights in China. He lost his freedom - so we want to visit him to show our support," he said.

Others have shown their dissatisfaction with the legal activist's treatment by posting photographs on the internet showing themselves wearing dark glasses similar to ones worn by Mr Chen.

The case has also attracted international attention.

Gary Locke, the US ambassador in China, recently wrote to the Chinese foreign minister, Yang Jiechi, to ask about Mr Chen.

The claims of attacks on activists outside Mr Chen's village sound, at the very least, plausible.

Rule of law?

When the BBC visited, it was clear the men who stopped us were well drilled and organised - although it was impossible to say who had hired them.

There appeared to be a chain of command: one man took took some money from our car and put it into his pocket, before someone else told him to put it back.

The men wore plain clothes, showed no identification and refused to answer questions about who they were. They did not ask before taking what they wanted.

After searching our equipment they gave it back and then told us to leave the village.

Plainclothes security officials stop the BBC from visiting Chen Guangcheng

Beijing-based lawyer Lan Zhixue said the government had offered no legal reason for restricting the activities of the blind activist, and Chinese law gave them no excuse.

"He should have the full range of freedoms - the freedom to move around, the freedom to speak out and the freedom to meet friends," he said.

The government does not appear to have even offered a veneer of legality in this case, a worrying development according to Mr Lan.

"Without the rule of law, how can we talk about harmony and stability?" he added, referring to watchwords often used by the Chinese government to justify its actions.

Other legal experts go further, saying the treatment meted out to Chen Guangcheng is common - and at least known by those at the very top of the Chinese Communist Party, if not authorised by them.

Jerome Cohen, an authority on China's legal system, said: "The leaders of China are very smart guys and they are very knowledgeable about the full scope of unrest and dissatisfaction."

Mr Cohen, a professor at New York University School of Law, said officials used repression because they feared that dissatisfaction, fanned by people like Mr Chen, could undermine their rule.

China likes to say it is a country ruled by laws; government spokespeople regularly repeat this mantra in answer to questions about the treatment of activists and dissidents.

In October, it issued an official document on the development it has made in establishing a "socialist legal system".

This has been "solidly put in place", declared the paper. Chen Guangcheng, and many others, might disagree.

- Published16 February 2011

- Published11 February 2011